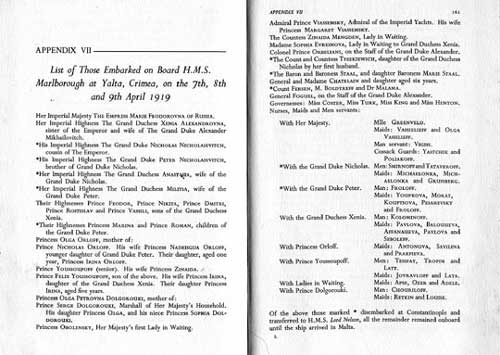

History - Rescue of the Imperial family from Yalta 1919

HMS Marlborough Evacuates Members of the Imperial Family, Yalta, April, 1919

Above, a Photo-card of the HMS Marlborough, autographed by many of the Imperial passengers who came on board.

Vice Admiral Sir Francis Pridham, KBE, CB, was the First Lieutenant of the HMS Marlborough, when it arrived in Yalta on April 7, 1919 under orders of the British Royal Navy to evacuate Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, sister of Queen Alexandra, and members of the Russian Imperial Family. He published his account of this historic event in his book "Close of a Dynasty", Allan Wingate Publishers, Ltd, London, 1956. We offer these brief excerpts and photographs for educational purposes only, and other reproduction is prohibited without first obtaining permission of the copyright holders.

On 4th April 1919, on a cold and misty morning, HMS Marlborough left Constantinople for Sevastopol, the Captain (C.D. Johson, CB, MVO, DSO), being entrusted with a letter from Queen Alexandra to her sister the Dowager Empress Marie of Russia, urging her to leave Russia before it was too late to escape from the Bolsheviks and telling her that HMS Marlborough had arrived and was ready to receive her on board and carry her to Malta and England. ...

Left, Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna on board HMS Marlborough.

On his return from Yalta and his interview with the Empress Marie, the Captain gave orders for the ship to proceed to Yalta the next day, 7th April, and on her arrival to start embarking those whom Her Majesty wished to accompany her. She had only consented to this on the understanding that she would not herself leave the country until arrangements were completed for evacuation of all loyal people in the neighborhood of Yalta who wished to leave. [Until that moment, the French High Commission had agreed to help provide the ships needed for the evacuation, but had just then declined, leaving the British alone in the responsibility for the evacuation.]

The number of those who would embark in HMS Marlborough with the Empress Marie was not known, but it was evident already that we were to be asked to take many more than we had been led to expect when we left Constantinople. No special arrangements to receive a considerable number on board had been made, the intention then being to bring away only Empress Marie and a few of those closest to her; in all perhaps ten or a dozen persons. Now it seemed clear that we must do our best to provide accomadtion and food for a far greater number of passengers.

For a start, all the officers' cabins at the after end of the ship were vacated, about thirty-five in all and wherever possible two or more bunks were arranged in each cabin. The Captain's apartments were, of course, set aside for Her Majesty, the Captain moving to his sea-cabin under the bridge. The officers so displaced arranged shakedowns for themselves in other parts of the officers' quarters. Unfortunately, only about thirty spare mattresses were available and such luxuries as sheets were at a premium, although all officers placed their own supplies at my disposal, for it fell to my lot to organise the accomodation of our guests. At the best of times, a man of war is not an ideal vessel for conveying passengers, and in this case it was impossible to provide even reasonable comfort and space; the food and cooking presented problems which caused us some additional anxiety, that was doubtless shared by the Captain's chef.

For two weeks except during meal-times, I lived almost entirely with our guests in the after part of the ship, and consequently had frequent opportunities for talking with many of them. I had enough foresight to record my impressions of the moment as well as some details of the events as they occurred. ...

After landing two officers at Yalta to help those who were to come on board HMS Marlborough, and on learning that the Empress Marie did not wish to embark at Yalta pier, we moved a few miles along the coast to a little cove called Koriez, which was within easy reach of Harax, the Empress's lovely summer palace. ...

We soon learned that Her Imperial Highness the Grand Duchess Xenia, the sister of the Emperor, and the Grand Dukes Nicholas and Peter, the Emperor's cousins, would be among those for whom we would have to arrange accomodation. ...

Right, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna on board.

Fortunately, before I had let any of our guests know which cabins to occupy, I noticed that more passengers were arriving on board and left the cabin where I was working with Count Fersen (on the staff of Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaievich) to find out when the Empress Marie was expected. Just outside the cabin, where the light was rather dim, I saw two unaccompanied ladies evidently uncertain as to where they should go. I was about to ask them who they were when I realized that one of them, an elderly little lady dressed in black, closely resembled our Queen Alexandra and could be none other than the Empress Marie herself. At this moment, Count Fersen came forward and after saluting the Empress presented me to her and to the Grand Duchess Xenia who accompanied her.

So, the great lady who had once been the Empress of All the Russias, arrived unheralded on board HMS Marlborough. ... Completely taken aback by such an unceremonious and unexpected meeting with Her Majesty, I escorted her and her companion to the Captain's quarters and was about to retire when the Grand Duchess asked me what Count Fersen and I had been doing. On hearing that I was in some doubt as to who and how many to expect on board, and when, to my great relief she said she would come with me and tell me how to allocate the cabins, it was evident that she had immediately and accurately apprised the situation and realized that if left to Count Fersen and me alone, the result was likely to be somewhat chaotic. From then on it was plain sailing. Count Fersen faded away, I think with a flea in his ear, and I found myself closeted with an extremely charming and capable woman who knew exactly what was entailed and had very clear ideas as to how the details should be settled, and that, most certainly, they would be so settled whatever Count Fersen may have schemed. So, the first list was quickly torn up and the job done in half an hour, including the impossible one for me, of giving the necessary orders to the Russian servants now beginning to arrive on board.

I was almost guilty of starting an argument with the Grand Duchess when she gave herself one of the smaller and darker cabins on the deck below, one of the many 'potted air' cabins behind the ship's side-armour. But I held my tongue on realising that she did this in order that the Empress's personal maid might occupy the cabin adjoining Her Majesty's sleeping cabin. I had selected that cabin for the Grand Duchess as being the most suitable for one of her rank. ...

Another matter soon began to cause me some anxiety; that of stowing the luggage. I was faced with the problem of stowing this in our very limited space, so collecting and segregating the trunks belonging to various parties, that they could be found easily should some disembark before the main party, as indeed happened. Many of those who came on board that first evening had arrived at an hour's notice and had brought little with them other than the clothes they were wearing, but driblets of trunks and packages had been brought off during the evening, mostly unlabelled or marked with Russian characters. By that night, we had literally tons of luggage aboard. A major difficulty arose from the fact that none of us could speak a word of Russian and could not, therefore give any directions to the servants. We had managed to deal with the luggage brought on board for Her Majesty quite satisfactorily since it was marked with her monogram and the quantity was small, but had it not been for Princess Marina, a tall handsome girl, and the elder daughter of Grand Duke Peter, offering to help as an interpreter, much of the rest of the luggage would have become hopelessly mixed up. Princess Marina acted as a very competent "first lieutenant", to whom I could refer any difficulties I met with dealing with Russian servants. the latter spoke no English and only rarely a little French, and being obviously dazed by their sudden upheaval and unusual surroundings they struck me at first as being rather indolent. ...

Left, Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaievich on board HMS Marlborough.

The Marlborough left Koriez after dark and anchored again off Yalta, where we were to remain for a few days before leaving for Constantinople. We had now embarked fifty persons, of whom thirty-eight were women.

Included in this number were H.I.H. the Grand Duke Nicholas and H.I.H. the Grand Duke Peter accompanied by their Grand Duchesses. The two latter, Anastasia and Militza, once konwn as 'the beautiful Black Mountain Sisters' were daughters of that old fox King Nichols of Montenegro. ...

The Grand Duke Nicholas, a magnificent looking man and six feet six inches tall, dressed always while on board HMS Marlborough in a splendid Cossack costume with the tall lambskin head-dress accentuating his great height, was an almost awe inspiring presence; a strong commanding personality tempered with great dignity and courtesy. ...

Another person of outstanding appearance, also wearing Cossack costume, was Prince Youssoupoff, formerly Governor of Moscow, perhaps the greatest landowner in Russia, and head of an ancient family which traces its descent from the first Caliph after the death of Mahomet. He was accompanied by his wife Princess Zinaida, his son Prince Felix Youssoupoff, his daughter-in-law Princess Irina Youssoupoff (daughter of the Grand Duchess Xenia) and his grandchild Princess Irina, aged about five. An interesting and intelligent young man, Prince Felix, educated at Oxford University, he spoke perfect English. ...

Left, Prince Felix and Princess Irina Yousoupoff on board.

With Grand Duchess Xenia had come five of her six sons, the Princes Feodor, Nikita, Dimitri, Rostislav and Vassili. Prince Feodor, her second son, being about twenty, and the youngest, Vassili, twelve. The younger ones, not old enough to undrestand the full force of the tragedy in their lives quickly became absorbed in the novelty of living in a man of war. Prince Vassili soon became a great favourite throughout the ship, as as sailors always love eager and enquiring children, this one was just the type of lively youngster that appealed to them. Prince Dimitri, who looked and spoke like an English schoolboy, was full of enthusiasm for all things naval, indeed he seemed to possess as complete a knowledge of British warships as I had myself. ...

I have now mentioned four generations of the Imperial Family of Russia, the Dowager Empress Marie (the Emperor's mother), the Grand Duchess Xenia (the Emperor's sister), Princess Irina Yousoupoff, and the little Princess Irina Yousoupoff. Since it is unusual for a British man of war to carry women on board for any lenght of time, HMS Marlborough recorded a unique experience in having on board for a fortnight, four ladies each of whom represented a different generation of the Emperor's family. ...

Above, three generations of the Romanov family. Grand Duchess Xenia with her granddaughter, Admiral Prince Vissemsky, Empress Marie, and the author, Lt. Pridham on the right.

The next day, 8th April, we spent embarking the remainder of those who would accompany Her Majesty, and further tons of baggage, in handling which our sailors were ably assisted on shore by a party of one hundred and twenty officers of the Imperial Army. I had suggested that those who were able to do so might bring on board as much bedding as transport would permit, and to my great relief some was now arriving in each boatload from the shore.

The four summer palaces with which we were concerned, Harax (belonging to the Grand Duke George, and in which Empress Marie had been living), AiTodor (the Grand Duchess Xenia), Tchair (the Grand Duke Nicholas) and Doulber (the Grand Duke Peter) were all fairly close together and not far from Yalta. This, while no attempt was made to bring away heavy goods, enabled our passengers to obatin the bare necessities they required for their unknown future. ...

That morning, I witnessed the arrival on deck of the Grand Duke Nicholas and saw for the first time the little ceremony which he observed daily while he was on board. With stately dignity, he approached the Empress, who was already seated on deck, presented himself to her with an immaculate military salute, and then paid her courtly and graceful homage by bending low and kissing her hand. ...

The news from up country was serious, the Bolsheviks having overcome the feeble resistance offered in the northern Crimea were now advancing rapidly southwards. Refugees were streaming into Yalta and on to the pier in ever increasing numbers, seeking safety. Soon a state of chaos reigned amongst this throng of terrified and distraught people. Children became separated from their parents and husbands from their wives and it is doubtful whether some of these unfortuante creatures ever met again. Many arrived on the pier with no other possessions than the clothes they wore. I saw one family arrive in such a state of utter panic that on reaching the harbour they jumped out of their motor car and dashed down the pier leaving the engine of the car still running. On that quay there were enough abandoned cars to provide at least one for every officer in the ship. However, the opportunity could not be taken for we were too busily occupied on more urgent business. In the evening we were warned by the police that a rising of the local Bolsheviks might break out at any moment, and at the former's request we kept searchlights playing on the town all through that haunted night.

The evacuation of Yalta, though much interfered with by a strong wind and rough sea, continued during the following three days. ... During the whole of this time a succession of people arrived on board asking to see the Empress Marie and to beg her to take them with her. I fear that Her Majesty was frequently greatly distressed by the pathetically urgent pleas which she was unable to meet. ...

Shortly before the evacuation of Yalta was completed, a British sloop embarked about four hundred of the Imperial Guard, mostly officers, who had collected at Yalta, for transport to Sevastopol. On sailing, the sloop steamed slowly round the Marlborough to allow those on board to salute the Empress Marie and obtain a last sight of her. Gathered on our quarter deck were a number of our distinguished passengers, including the Empress and the Grand Duke Nicholas. The Empress, a little lone figure, stood sadly and apart from the others near the ensign staff, flying, of course, the White Ensign, while the voices of the Imperal Guard singing the Russian Imperial Anthem drifted across the water to her in last salute. None other than that beautiful old tune, rendered in such a manner, could have poingantly reflected the sadness of that moment. The memory of those deep Russian voices, unaccompanied, but in the perfect harmony which few but Russians can achieve, has surely never faded from the minds of those who were privileged to witness this touching scene. Until long after the sloop had passed there was silence. No one approached the Empress, while she remained standing, gazing sadly after those who, leaving her to pass into exile, were bound for what seemed likely to be a forlorn mission. Few are known to have survived the next period of fighting outside Sevastapol.

This proved to be the last occassion on which the Russian Imperial Anthem was rendered to a member of the Imperial family within Russian territory.

Above, Empress Marie and Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaievich during the singing of the Imperial Anthem for the final time.

On 11th April 1919 our promise to Her Majesty The Empress Marie had been fulfilled, the evacuation of Yalta was complete and HMS Marlborough could sail for Constantinople.

We had then on board twenty members of the Imperial family, including two small children, and in addition twenty five ladies and gentlemen of the suites of Her Majesty, the Grand Duchess Xenia and the Grand Dukes Nicholas and Peter. Maids, servants and others added a further thirty six to the number for whom accomodation, of a kind, had been found on board. I estimated that by the time we sailed that day, in addition to our passengers, we were carrying some two hundred tons of luggage.

All that morning the Empress had been receiving they many who came on board to seek her help or to say goodbye; there was no more now that she could do for them, but up to the last moment she was deeply concerned for those who could not accompany her in the Marlborough.

In the afternoon the ship, unheralded and without escort, moved silently from the anchorage off Yalta and headed into the mist of the Black Sea. Our passengers stood for long on deck gazing astern with full hearts as the beautiful coast line of the Crimea faded from their view. We did not know it at the time, but with our departure all members of the Imperial Romanov family then alive had left Russia forever, and the dynasty, which came into power in 1613, was ended.

Above, the deck of the HMS Marlborough after leaving Yalta.

Please send your comments on this page to Rob Moshein

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map