History - Imperial Court Costume

Women's Imperial Court Costume in Imperial Russia

by Nick Nicholson

"The splendour of the dresses was the finest coup d'oeil I had ever seen." (1847)

Until the coronation of Peter I (the Great), the court of Muscovy was known for its sartorial splendor and the isolation in which it developed. Russians had inherited a religious and sumptuary legacy from Byzantium, and so the clothes of the Russian court were still the rich silks of the east; long robes heavily embroidered and sewn with pearls and precious gems. These caftans (robes) and Sarafans (over robes) would have been at home in Beijing, Constantinople, Samarkand, or any of the legendary cities along the Silk Route. Russian dress had remained largely unchanged from the 10th century until the 17th.

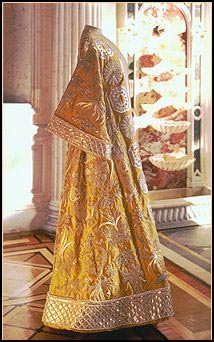

Left: Fancy Court Gown of Alexandra Feodrovna, reproducing the dress of the Tsarina Marfa Ilyinichna, wife of Tsar Alexei Michaelovitch, 1903.

Left: Fancy Court Gown of Alexandra Feodrovna, reproducing the dress of the Tsarina Marfa Ilyinichna, wife of Tsar Alexei Michaelovitch, 1903.

When Peter I (the Great) took the throne, he advocated the Europeanization of the Russian Empire. Discarding the ancient title of Tsar and assuming that of Emperor, he moved the capital to the westernmost port of the Empire, and created the breathtaking city of Saint Petersburg on the Neva River, near the Gulf of Finland. Peter also abolished the ancient modes of dress and manners of living that had marked the Muscovite court. Women were removed from the Terem (isolated living quarters), and all members of the court were required to adopt western dress.

In 1700, Peter the Great made westernization official, and issued the sweeping sumptuary reforms of 1700 discouraging the wearing of Russian dress both at court and at home. By the end of the first decade of the eighteenth century, its use had become virtually extinct among members of the Russian nobility, though some gentlemen still wore the "caftan" at home on their country estates.

By the early 18th century, dress at Peter's court was not dissimilar to that of the courts of Central Europe, though he still aspired (as did all monarchs) to the level of sophistication seen in France at the court of Versailles. In the new, Imperial Russia, as in all other European Courts, public ceremonials required a specific and magnificent style of dress which reflected the power of the autocracy, yet which also reflected the national identity of its people.

At his new court in St. Petersburg, Peter the Great ordered women to dress first in the popular German and Austrian fashions which came to Russia through Poland and Hungary. By the end of the first quarter of the eighteenth century, French fashion had found its way to Russia via engravings and the beautifully dressed dolls which were sent as an example of the skills of French dressmakers, upholsterers, and fabric merchants. French fever caught on, and soon overtook the pervious fashions in preeminence.

Above left; Maria Feodrovna, circa 1770; right, Catherine the Great.

By the reign of Catherine the Great, French style in dress was firmly established at the Russian court for official occasions - vast panniered (hooped) gowns and tall wigs were de rigueur. In her "hermitage," and at leisure, however, Catherine consciously wore Gallicized versions of the Russian caftan, sarafan, and kokoshnik to emphasize her "Russianness" to her Court - a court very well aware that she was foreign - born, and had usurped the throne.

By the early 1830's fashion in Russia, and particularly dress considered appropriate for court functions, had little coherence. The risque styles of the French empire had been considered vulgar, and the long trains and high feathers of the English regency had no resonance for Russians. Women at court wore whatever they considered both appropriate and a la mode until finally, Emperor Nicholas I had had enough. Nicholas, Germanic at his core, felt the need to see unity among the women of his court, as he saw among the men, who were required to wear military dress or court uniforms at all times. This allowed Nicholas (and all courtiers) to discern rank immediately, and this eased the issues of protocol and etiquette which plagued the court because of its inorganic and irregular development over the previous two centuries.

As part of his vast efforts to codify the organization of the Court and State, Nicholas I and Count M.M. Speransky published the Code of Laws of the Russian Empire in 1833. This massive set of laws incorporated everything pertaining to the Empire, from the Role of the Emperor, to the rights of Russian subjects. In addition to the 40 volumes of civil laws, there was a single volume reserved for the laws enacted during the reign of Nicholas I himself; and one of these laws was the Edict on Court Dress.

Left; Alexandra, wife of Nicholas I.

Left; Alexandra, wife of Nicholas I.

The edict specified that women at the Russian court were to wear "Russian Dress Uniforms." (Paradnaya Plat'e) This was initially described as "a white embroidered silk gown, with an embroidered velvet overdress with long, open sleeves in the Muscovite style." The skirts were rouched and fastened at the waist, held together by a gold cord. The shape of the skirt was bell-like and full, the sleeves slightly puffed at the shoulders. This was a combination of the current "Romantic" style of fashion, and the ancient Russian style. As a result, this costume reflected the Russian nationalist traditions so favored by Nicholas I, and its usage became law. These dresses were extraordinarily cumbersome and heavy, the bodices tightly boned. The dress trains were interlined and reinforced to support the great weight of the gold embroidery. Though picturesque, the dresses were unwieldy, and women of the court began to refer to dressing for Court occasions as "putting on the armor."

While other courts moved on, changing and adapting the dress of their courts, Russia stayed firmly in its Slavic historical mode, and so, from 1834 until 1917, the unusual ethnic dresses of Russian court ladies became instantly recognizable, and a source of pride at home and abroad - Russian women stood out in foreign courts, and at home they made a unforgettable impression on visitors and natives.

The first change to this new dress happened in the 1840s, when the velvet overdress (sarafan) and silk under dress (caftan) were adapted to fit contemporary corseted fashions. The costume became three separate pieces, rather than two; an embroidered white silk underskirt, over which was placed a waist-hung train, and a corseted bodice which incorporated the long muscovite sleeves and an embroidered white silk "corsage." The illusion of the assembled tripartite gown was similar in effect to that of a robe worn over an under dress.

Also required to be worn was the Kokoshnik, a diadem-like headdress. For women of the Imperial family these were originally jewel-studded velvet, with pearl-trimmed plain velvet for their attendants. Long, floor-length tulle veils were worn by married ladies. By the late nineteenth century, however, most women of the Imperial family had abandoned this simpler style in favor of tiaras made entirely of precious stones retaining the prescribed kokoshnik shape. These stunning works by Faberge and Bolin were masterpieces of the Russian jeweler's art, and became very fashionable throughout Europe; the Tiare Russe became a staple of jewelers such as Cartier, Boucheron, Chaumet, and others.

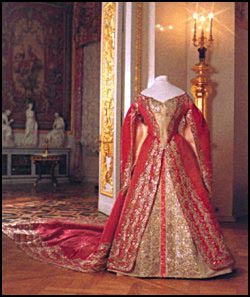

Left; Empress Alexandra in a massive Imperial tiara of diamonds and pearls from the era of Catherine the Great, a heavily embroidered court gown and the scarlet ribbon of the Order of St. Catherine. This same dress is shown below.

Left; Empress Alexandra in a massive Imperial tiara of diamonds and pearls from the era of Catherine the Great, a heavily embroidered court gown and the scarlet ribbon of the Order of St. Catherine. This same dress is shown below.

The materials, construction, and execution of court gowns were strictly controlled. In the Edict on Dress, it states: "the trains and dresses of the ladies shall be embroidered in the same manner as that of court Chamberlains of corresponding rank." This was, however, a loose requirement. While each Court Chamberlain's costume was embroidered identically, no such uniformity existed in the female costumes. The style of decoration was largely up to the woman who ordered the gown, but the extent of the expensive decoration was determined by the court. The gowns were expensive. In 1885, a gown ordered by Princess Yusupova was 1500 roubles (the Faberge Imperial Egg of 1888 cost the same!), and this gown would have been nowhere near as expensive as one ordered for a member of the Imperial Family. The dresses took anywhere from 6-8 months to complete, and so, the embroidered panels for the sleeves, train, and bodice were often executed in advance, and stored flat. Women would arrive at the dressmaker, choose the panels which suited her taste, position, and pocket book, and the dress would be assembled, boned, and finished for her as at any couture establishment. The dresses were frequently returned for repairs and alterations, and were sometimes sent to be cleaned as well.

Above: Court Gown of Alexandra Feodrovna, circa 1890's

Gowns of cloth of gold and cloth of silver were reserved for the Empress and the daughters of the Emperor. When the Empress wore cloth of gold (generally only at their coronation), the Grand Duchesses could wear cloth of silver. As most Empresses preferred cloth of silver (it was more flattering, and far less heavy), the Grand Duchesses rarely had the opportunity to wear it except at their weddings, when it was required. For other occasions, the Grand Duchesses wore velvet gowns in a color of their choosing, which was reserved for their exclusive use.

Left, Court Gown of Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna, 1894; right, Alexandra Feodrovna's Court Gown by Bulbenkova, circa 1890's.

Attendants to the Empress (or after 1894, Empresses) and the Imperial family wore court gowns in two colors, garnet red and emerald green. The hierarchy was sophisticated and rigid. The highest title was that of Chief Stewardess of the Household, who, as a married woman, wore a green velvet court gown embroidered in gold, with a train, the length of which was determined by her rank (chin'). After the Chief Stewardess came Ladies-in-waiting (second and third class in the ranks of the Imperial Household, determined by length of service.). The Ladies-in-waiting were married women of noble birth selected by the Empress. They also wore the green velvet, but with shorter trains. The fourth class of female attendants was Full Maids of Honor of the Bedchamber. These unmarried women of the highest nobility wore the same types of gowns, but in crimson velvet. They also had small capes, which covered the bare shoulders revealed by married ladies. These women served the empresses exclusively. In the mid-nineteenth century, there also existed the positions of Chief Ladies (the fifth class) who were the equivalent of Ladies-in-Waiting, but served the Grand Duchesses and Princesses of the Blood, and the sixth class position of Chief-Ladies-In-Waiting and Maids of Honor of the Bedchamber. By 1881, the fifth through seventh classes were abolished as redundant.

The ladies of the Court also had some insignia - stewardesses of the household, ladies-in-waiting and maids-of-honor could wear portraits of the Empresses decorated with diamonds on the right side of the breast, if they had been so honored by the Empress. These women were known as "Damy Portrety" or Dames-a-portrait. The maids-of-honor were required to wear "chiffres" crowned monograms of the Empresses or Grand Duchesses whom they served decorated with diamonds on St. Andrew's blue ribbon on the left side of the breast. Many of the highest level of these women were also members of the Order of St. Catherine, and these women also wore the sash, and badge of the order.

The title of Maid-of-Honor was awarded most frequently. In 1881 189 of 203 ladies of the Court were Maids-of-Honor and by 1914 - 261 of 280. The titles of Maid-of-Honor and Maid-of-Honor of the Bedchamber could be given only to single women. Under Nicholas I a "suite" of Maids-of-Honor was established, and assigned to serve the Empress and the Grand Duchesses. They were 36 all in all and were called "Maids-of-Honor of the suite." The Maids-of-honor who were not "of the suite" had no permanent duties. The Maids-of-Honor of the "suite" received their dowry from the Court when they married. Some of them received higher titles after their marriages, but most were dismissed from the Court after their marriage. These women still had the right to be introduced to presence of the Empress, and were invited to the Grand Balls in the Winter Palace with their husbands irrespective of their husbands' official ranks. These women were highly prized as wives because of their unequalled Court Access, even after the termination of their employment at court.

The embroidery of these gowns was extraordinary. Sometimes featuring floral motifs, or rocailles inspired by the architecture of the capital, the art of the embroidery was at a very high level. These court dresses were frequently shown at international textile exhibitions as a showcase for Russian talents in the field. The right to produce Court Gowns was strictly controlled, and in the 20th century was limited to:

Olga Nikolaevna Bulbenkova (c. 1835-1918)

Founded a fashion house in St. Petersburg in the mid-nineteenth century, which survived until 1917, and was known as Madame Olga's. The house was popular for its court gowns, the Paradnaya Plat'e. Gold and Silver embroidery was executed for Mme. Olga by the workshops of I.L. Vasiliev at the Yekaterinsky Canal. Dresses ordered for the imperial family were embroidered at the Novotikhvinsky Convent workshop that specialized in this gold threadwork. In the early 20th century, Olga's niece took over the practical management of the house.

Izembard Chanceau

Proprietor of a Petersburg fashion house which also made formal court gowns in the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries. The work of Izembard Chanceau is recognized by its use of paillettes, or sequins, rather than the ornate gold thread embroidery which was Madame Olga's hallmark.

A.T. Ivanova

St. Petersburg dressmaker who also had license to produce court gowns for private clients in the early 20th century. She largely produced gowns for private clients. Ivanova was a popular dressmaker, and her firm survived the revolution. Ivanova and her chief rival Lamanova, both became costume designers for film and theater in the Soviet era.

The Soviet period saw the end of not only the wearing of court attire, but the virtual extinction of the Russian art of ecclesiastical embroidery. Many of the women who were capable of this type of embroidery fled the revolution, and moved to France, where they were eagerly employed by couturiers such as Patou, Lanvin, and Chanel.

Convents are beginning to revive the art of embroidery in Russia, but the days of the paradnaya plat'e are over.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Russian Style 1700-1920; Court and Country Dress from the Hermitage Barbican Editions, London, 1987

Sharaya, N. and Moiseyenko, Ye., Costume in 18th to Early 20th Century Russia Leningrad, 1962

Korshunova, T.T. Costume from 18th to Early 20th century Russia from the collections of the Hermitage Leningrad, 1982

History of Russian Costume Metropolitan Museum, New York 1976

Onassis, J. (ed.) In the Russian Style Viking, New York 1977

Code of Laws of the Russian Empire, 1834 Facsimile edition, New York 1983, NYPL.

Please send your comments on this page to Nick Nicholson

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map