Palace Personalities - Dominic Lieven on Nicholas and Alexandra

Excerpt from Nicholas II by Dominic Lieven

CHAPTER 3

Tsar and Family Man

On 1 January 1894 the Tsarevich Nicholas wrote in his diary, 'Please God that the corning year will pass as happlly and quietly as the last one. In fact 1894 was to transform Nicholas's existence. At the begining of the year the heir was first and foremost a young Guards officer, much of whose life was devoted to reading, dancing, skating, the opera and his mistress, Mathilde Ksheshinskaya. Twelve months later he was Emperor of all the Russias, the bearer of theoretically absolute power over a vast empire. He was also a married man.

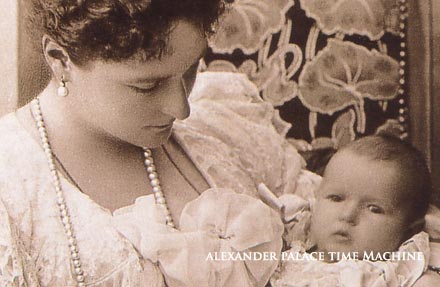

Nicholas's bride was Princess Alix of Hesse, the youngest daughter of Grand Duke Louis IV of Hesse and his wife Alice, who was herself Queen Victoria's second daughter. In 1884 Alix's elder sister, Elizabeth, had married the Grand Duke Serge, younger brother of Alexander III. Alix had her first experience of Russia, aged 12, when she attended her sister's wedding. There she met the 16-year-old Tsarevich Nicholas for the first time. Subsequently they met again, both in Russia and abroad. In December 1891 Nicholas confided to his diary that it was his 'dream - to get married one day to Alix of Hesse .

The heir's choice was eminently suitable. Many of Nicholas's Romanov relations were to marry a bewildering collection of ballerinas, commoners and divorcees in the quarter century before the 1917 revolution. By contrast the heir's eye had lighted on a very beautiful young woman closely connected to many of the greatest royal families in Europe. There is no evidence that Alexander III or the Empress Marie opposed their son's choice of bride. On the contrary, almost Nicholas's first thought after his engagement was that the news would delight his parents. The problem with Alix was quite different. A Russian Empress had to be of the Orthodox faith. Therefore any foreign princess marrying the heir to the throne must convert to Orthodoxy. This the young Princess of Hesse was not prepared to do. Not until April 1894 did Alix change her mind. On 2 April Nicholas had set off with a large contingent of Romanovs to attend the wedding of Allx s brother, Grand Duke Ernest Louis of Hesse, to another grandchild of Queen Victoria, Princess Victoria ('Ducky') of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Much of Europe's Protestant royalty descended on Darmstadt for the occasion, including Queen Victoria herself and the Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany. On 5 April Nicholas was left alone with Alix for a time. 'She has grown wonderfully more beautiful', wrote the Tsarevich in his diary, 'but was looking very sad. They left us alone and then began between us the conversation which I had long since greatly wanted and yet very much feared. We talked until twelve but without success, she is very opposed to a change in religion.'

Three days later the young princess gave in. 'A wonderful unforgettable day in my life,' wrote Nicholas,

the day of my betrothal to my beloved Alix. After 10 o' clock she came to Aunt Miechen and, after a conversation with her, we sorted things out together. God what a mountain has fallen from my shoulders; how this joy will make dear Mama and Papa rejoice! I walked around as if in a dream all day, not fully understanding what had happened to me! Wilhelm [the Kaiser] sat in a neighbouring room and awaited the end of our conversation with the aunts and uncles.

No one can be sure what caused Princess Alix to change her mind. It was certainly not overt pressure from her relatives nor a simple desire to wear a crown, for not long before she had stoutly resisted attempts to marry her to the eldest son of the Prince of Wales, 'Eddie', the Duke of Clarence. Perhaps the atmosphere surrounding her brother's wedding and the ill-suppressed hopes of many of her relatives influenced her. Perhaps she felt a little insecure at the thought of losing her position as leading lady in Hesse-Dannstadt to her brother's bride. The advice of her sister, Elizabeth, who became a voluntary and passionate convert to Orthodoxy in 1891 may have been important. When staying on her sister's estate at Ilinskoe, near Moscow, Alix seems to have conceived that romantic love for the Russian peasantry and village life which was so strongly to mark her thinking as Empress. But probably the simplest answer is the best one. Not even Alix's worst enemies ever denied that she loved her husband devotedly. And if love for a handsome, sensitive man with high ideals was allied to a romantic excitement at the prospect of life in Russia and the challenge of a throne, no young woman could fairly be blamed for that.

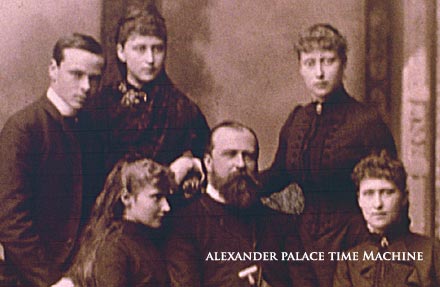

Alix's father, Grand Duke Louis IV, had died in 1892. Though she loved her father and was greatly upset by his death, it does not seem that Alix inherited much of his personality. The Grand Duke was a rather amiable, easy-going and unintellectual man. He was a professional soldier, and in later life Alix used to take pride in calling herself a soldier's daughter. She shared her husband's liking for military pageantry and the officer's code of values and behaviour. Perhaps her love of flowers was also inherited from her father, an enthusiastic gardener. Darmstadt in the broader sense did, however, influence the young princess in ways that mattered later in Russia. The Grand Duchy and its royal family were not rich, especially after the wars of 1866 and 1870-1. Managing the household first of her father and then of her brother, the young princess learned habits' of thrift and careful accounting which were to contribute to her unpopularity among the extravagant, generous and often reckless aristocracy of Petersburg.

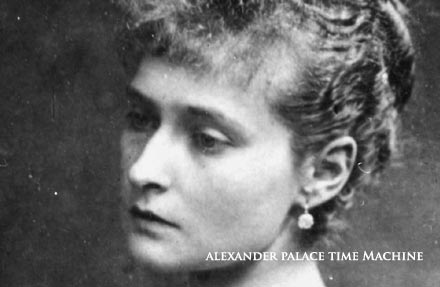

Alix was in some respects very similar to her English mother, Princess Alice. Alice was an intelligent woman, who shared the intellectual interests and the seriousness of purpose of her father, the Prince Consort, and her elder sister, Victoria, the mother of Wilhelm II of Germany. Like Victoria she encountered much criticism from German courtiers because of her English ways and sympathies, but Alice was more tactful than her elder sister and Darmstadt a less difficult place for an English princess than the intrigue-ridden and arrogant Prussian capital.

Alice was a deeply serious and thoughtful Christian.

The princess's absorption with religion began in the period of nervous strain after the death of her father. She read Professor Jowett's Esssays and Reviews and F.W. Robertson's Sermons, starting her along the path to spiritual freedom. She conversed with the leading churchmen, who were among the few visitors to the Queen in the initial mourning period, and before she was twenty had engaged Dean Stanley in an earnest discussion of the Apocalypse and the Psalms.

In Darmstadt Princess Alice became a great friend and admirer of David Strauss, the author of Life of Jesus and a biblical scholar of worldwide renown and radical views. The two used to discuss not merely religious questions but also Voltaire. Strauss read lectures on religious topics to the Princess, and when these were published he dedicated them to her. Strauss did this unwillingly, knowing that in parochial and God-fearing Darmstadt the association of Princess Alice with unorthodox religious ideas would cause a stir. But where her personal friendships and her religious convictions were concerned, Princess Alice was prepared to scorn public opinion. Later, in the much wider, crueller and more important context of Russia, her daughter Alix was to do the same.

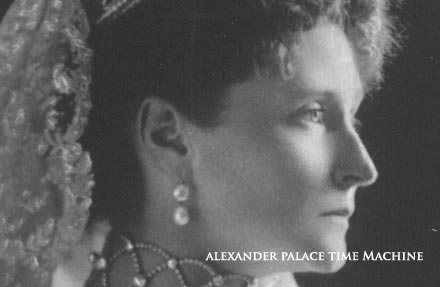

An intelligent and well-informed friend wrote of Princess Alice that 'Christianity to her was not a profession to be made lightly. If she could not embrace its essential doctrines with her whole soul and without reservation it became a meaningless lip-service which it was her clear duty to abandon.' Like her mother, Alix was a fervent Chnstian. She abandoned Protestantism only after a great struggle. In her bedroom at Tsarskoe Selo 'was a little door in the wall, leading to a tiny dark chapel lighted by hanging lamps, where the Empress was wont to pray'. When in Petersburg, the Empress used to go to the Kazan Cathedral, kneeling in the shadow of a pillar, unrecognized by anyone and attended by a single lady-in-waiting. For Alix life on earth was in the most literal sense a trial, in which human beings were tested to see whether they were worthy of heavenly bliss. The sufferings God inflicted on one were a test of one's faith and a punishment for one's wrongdoings. The Empress was a deeply serious person who came to have great interest in Orthodox theology and religious literature. She loved discussing abstract, and especially religious, issues, and her later friendship with the Grand Duchesses Militza and Anastasia owed much to their knowledge of Persian, Indian and Chinese religion and philosophy. Alix 'zealously studied the intricate works of the old Fathers of the Church. Besides these she read many French and English philosophical books.'

As Empress, Alix held to an intensely emotional and mystical Orthodox faith. The superb ritual and singing of the Orthodox liturgy moved her deeply, as did her sense that through Orthodoxy she stood in spiritual brotherhood and communion with her husband's simplest subjects. But alongside this strain of Christian belief, Alix was also a born organizer, an efficient administrator and a passionate Christian philanthropist. Though her interests included famine and unemployment relief, and professional training for girls, her charitable work was above all concerned with help for the sick and the world of medicine. Typically, even on holiday in the Crimea, Alix toured the hospitals and sanatoria in the neighbourhood, taking her young daughters with her because' they should understand the sadness underneath all this beauty'. Setting up medical rehabilitation centres for the wounded, busying herself with training young women, and organizing hospitals and medical services in war-time - all of this was very reminiscent too of the activities of Alix's mother. Like her daughter, Alice was an efficient, practical, down-to-earth administrator who loved organizing a range of charitable activities. Also like Alix, the world of nursing and care for the sick was closest to her heart. Princess Victoria of Hesse recalled the Franco-Prussian War in her memoirs, when 'my mother was very busy with Red Cross work and regularly visited the wounded, both German and French, and I often accompanied her'.

In both mother and daughter the spirit was a good deal stronger than the flesh. Both were exhausted by numerous pregnancies. Already tired and ill by her late thirties, Alix once wrote that 'Darling Mama also lost her health at an early age.' Devoted mothers, both women insisted on nursing their own children whenever they were sick. When Nicholas II contracted typhoid in 1900 Alix nursed him herself, day and night. 'I rebelled at a nurse being taken and we managed perfectly ourselves.' Unfortunately she added, 'now I suffer from head and heartache, the latter from nerves and many sleepless nights'. When her children went down with diphtheria in 1878 Princess Alice exhausted herself looking after them. When she too contracted the disease she was unable to resist it and died on 14 December 1878, aged only 35.

Alix and her mother were similar not only in their physical frailty but also in their highly strung, passionate temperaments. Princess Alix was a proud, strong-minded, very emotional woman who fought to control her anger and nerves. Her mother once complained to Queen Victoria that 'people with strong feelings and of nervous temperament, for which one is no more responsible than for the colour of one's eyes, have things to fight against and put up with, unknown to those of quiet, equable dispositions, who are free from violent emotions, and have consequently no feeling of nerves. . . One can overcome a great deal - but alter oneself one cannot.'

When her mother died Alix was 6 years old. Simultaneously she lost her sister and playmate, May, also to diphtheria. One can only guess at the impact of these deaths on the small child, though Baroness Buxhoeveden may well be right in suggesting that they 'probably laid the foundations of seriousness that lay at the bottom of her character'. The gap in the children's lives left by their mother's death was to some extent filled by Queen Victoria. The Queen frequently visited Darmstadt, and the Hesse family took a long annual holiday in England. As the youngest and most vulnerable of the Hesse children, Alix was the Queen's favourite. Grandmother and granddaughter always adored each other. As Empress, the only time when Alix was seen to weep in public was at the memorial service for Queen Victoria at the English church in Petersburg. Lili Dehn, who knew Alix very well, believed that she owed a good deal to Victoria's influence.

The Empress inherited much of her illustrious grandmother's tenacity of purpose, and she refused to be dictated to . . . her morals were the ultra-strict morals of her grandmother. . . in many ways she was a typical Victorian; she shared her grandmother's love of law and order, her faithful adherence to family duty, her dislike of modernity, and she also possessed the 'homeliness' of the Coburgs, which annoyed Society so much. . . Queen Victoria had instilled in the mind of her granddaughter the entire duties of a Hausfrau. In her persistent regard for these Martha-like cares, the Empress was entirely German and entirely English - certainly not Russian.

In the first days of the 1917 revolution, when all the imperial children were ill with measles, Lili Dehn discovered to her surprise that the Empress not only knew, how to make a bed, but was also 'especially expert in changing sheets and nightclothes in a few minutes without dlsturbmg the patients' Alix commented, 'Lili . . . you Russian ladies don't know how to be useful. When I was a girl, my grandmother, Queen Victoria, showed me how to make a bed. . . I learnt to do useful things in England. '

It may well be partly true that Alix's 'English point of view on many questions in later life was. . . due to her many visits to England at this most impressionable age', in other words during childhood and adolescence. In any case, Princess Alice had always remained 'intensely English', and 'life in the Palace was organised on English lines, and was so carried on after the Princess's death'. The nursery, ruled over by Mrs Orchard, operated according to the English system of fresh air, simple food and a strictly observed timetable. Thence, Alix graduated to an English governess, Miss]ackson, an intelligent woman under whose direction 'the princesses were trained to talk on abstract subjects'. Not surprisingly, 'English was, of course, her natural language' and England the focus for many of her loyalties. During the First World War, Alix was to be deeply reviled in Russia as a 'German', whose sympathies lay with Russia's enemies. There was no justice whatever in this, for Alix never had the remotest loyalty to the Prussian-dominated German Reich or to its ruler, Wilhelm II. Had war broken out between Russia and Britain, however, as was entirely possible at any time between 1894 and 1906, Alix would most certainly, and more justifiably, have been denounced as an Englishwoman. Such was the inevitable fate of a foreign consort amidst the nationalist passions of late Victorian Europe. In later life Queen Victoria became doubtful of the wisdom of dynastic marriages through which her daughters and granddaughters were exposed to the strains and perils that faced foreign queens at European courts. It was Alix, for whom the Queen had particular affection, who was to confront these perils in their most cruel form. Not surprisingly, Victoria's joy at her granddaughter's love for Nicholas and her splendid marriage was tempered by fear for her fate on such a great, but also such a dangerous, throne.

The most tragic inheritance Alix received from her mother and grandmother was, however, the disease of haemophilia. This hereditary ailment is generally transmitted through females but strikes only males. Its effect is to stop the blood from clotting which, in the era before blood transfusions, was a certain recipe for prolonged suffering and offered the probability of an early death. Queen Victoria's son, Leopold, was killed by this disease, from which Princess Alice's younger son also appears to have suffered. At first glance, therefore, it might seem extraordinary that the Romanovs could allow the heir to the throne to run the medical risks that marriage to Alix entailed. In fact, Alexander III and his wife clearly knew nothing about the disease or the risks involved. Although Alix's elder sister had married the Grand Duke Serge the couple were childless, so the Russian imperial family had had no reason to confront the issue of haemophlia. Of course, having seen the disease destroy one of her sons, Queen Vlctoria herself must have known something about It. But the Queen can hardly be accused of deceiving the Romanovs or exposing them deliberately to danger, since she had done her utmost to persuade Alix to marry the Duke of Clarence, who stood in the direct line of succession to the British throne. The issue of haemophilia was 'a highly delicate matter rarely discussed in. royal circles. . . The whole subject was more or less taboo while Queen Victoria was alive.' The question was in any case complicated by the random nature of the disease. Of Queen Victoria's four sons only one was affected. Nor was haemophilia transmitted through her eldest daughter, Victoria, to Kaiser Wilhelm II, as could very easily have happened. Instead it was the descendants of her second and fourth daughters, Alice and Beatrice, who were affected.

Even had the risks been better understood, however, it is by no means certain how Nicholas and his parents would have reacted. In Japan in 1920 a huge political storm was caused by revelations that the intended bride of Crown Prince Hirohito came from a family in which colour blindness was a common affliction. The idea that any kind of hereditary ailment might be introduced by marriage into the imperial family caused justified consternation. By contrast European royalty appears to have been extraordinarily careless about such matters. To preserve royalty's status, cousins inter. married with no regard to eugenics. Haemophilia was treated no differently. In 1914, for instance, the possibility of a marriage between the Romanian Crown Prince and Nicholas II's eldest daughter was widely canvassed without anyone, seemingly, raising the issue of haemophilia. Unlike in Nicholas II's case, when in 1905 King Alfonso XIII of Spain proposed to marry Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenburg, another of Queen Victoria's granddaughters, the Spanish court does appear to have been warned of the risks involved. Alfonso seems, however, to have shrugged off these warnings, subsequently never forgiving his wife for the fact that two of his four sons were haemophiliacs. Nicholas II's case was more tragic than that of Alfonso in the sense that his only son, born at the end of his wife's child-bearing days, was struck by the disease. It is a measure of the Tsar's sensitive and chivalrous nature not to mention his deep love for Alix, that never once did he blame her for 'the fact that', in Alfonso's words, 'my heir has contracted an infirmity which was carried by my wife's family and not mine'. Haemophilia helped to destroy Alfonso's marriage, causing him to turn away from his wife in bitterness and even revulsion. If it were possible, their son's disease seemed to bring NIcholas and Alix closer together than ever.

In the summer of 1894, however, all thoughts of tragedy and disease were far from Nicholas's mind. The Tsarevich and his fiancee were deeply in love, In June he received his parents' permission to visit Alix in England. The day after his arrival he wrote in his diary, 'What happiness I felt, waking up this morning, when I remembered that I was living under one roof with my dear Alix.' The next few weeks passed blissfully, though not even the claims of his fiancee could stop Nicholas from visiting the barracks of the British Guards and revelling in the drill and horsemanship of the troops, From the moment of his departure every day that passed without a letter from Alix was torment. To guard against such misadventures Alix had carefully inserted loving messages in his diary for weeks in advance. Told by Nicholas of his affair with Ksheshinskaya, Alix wrote, 'God forgives us. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us. . . your confidence in me touched me, oh, so deeply and I pray to God that I may always show myself worthy of it.'

The Tsarevich's idyllic mood was, however, to be destroyed in the early autumn of1894 by his father's illness. In January 1894 Alexander had been very unwell, his doctors stating that the problem was influenza. Alarm spread in court and government circles, where it was recognized, in the words of General Kireev, that for all his 26 years the heir was still a child, with little training to take over the reins of government. By early March fears for Alexander's life had passed, but Lambsdorff reported that 'our monarch appears thinner, above all in the face; his skin has become flabby and he has aged greatly'. By late summer the Tsar's increasing tiredness was again causing worry, though not yet alarm. Professor Zakharin, brought in for consultations from Moscow, calmed the imperial family by saying that Alexander's life was not at risk. Nevertheless, he and Dr Leyden agreed on a diagnosis of nephritis, complicated by 'exhaustion from huge and never-ending mental work'. The Tsar stuck to his autumn routine of visiting his hunting lodge at Spala in Poland, but on 30 September he was forced to decamp to the Crimea, whose warm climate would, it was hoped, help him to recover. Although in early October Alexander was still travelling in the Crimea, by the middle of the month he was sometimes confined to bed all day and the Tsarevich had begun to read state documents on his father's behalf. On 20 October the Tsar's brothers, Serge and Paul, arrived at Alexander's bedside from Moscow. Two days later Alix arrived, Nicholas commenting, 'what joy to meet her in my own country and to have her so close - half my cares and souow seem to fall from my shoulders'. The Tsarevich was to need all the support he could get, for on 1 November Alexander III died. His appalled heir commented in his diary: 'My God, my God, what a day. The Lord has called to himself our adored, dear, deeply loved Papa. . . This was the death of a Saint! God help us in these sad days! Poor dear Mama. '

The weeks that followed his father's death were a nightmare for the young Emperor. Together with the numbing shock of the loss came awareness of the new and enormous responsibilities which he was ill-equipped to face. The day-to-day business of government, including audiences with ministers and receptions for other officials, bore down upon him. The endless series of religious services following the death of an Orthodox monarch took up much of his time. Still worse were the many receptions for Russian and foreign delegations who arrived for Alexander's funeral and to pay their respects to the new monarch. Frequently Nicholas had to make speeches at these receptions, something to which he was little accustomed and which caused him great strain. Worst of all in a way were the innumerable members of foreign royal families who descended on Petersburg for the funeral and who had to be met at railway stations, accommodated in the imperial palaces and treated with due deference and attention. On 18 December, the eve of the funeral, Nicholas received so many delegations that 'my head was dizzy'. Two days later, after greeting and dining with two hundred guests, 'I almost howled'. On 26 November court mourning was lifted for a day and Nicholas and Alix were married. Two days later the Tsar was so busy that he only saw his wife for one hour. Not surprisingly, the strain told on him. Alix (who was her husband's aunt by marriage) wrote in Nicholas's diary, 'it's not good to grind your teeth at night, your aunt can't sleep' .

The new monarch appeared rather lost in his role. On 13 November Lambsdorff commented that 'the young emperor, evidently, was shy about taking his proper place; he is lost in the mass of foreign royalties and grand dukes who surround him'. On 27 January 1895 Lambsdorff again noted that 'His Majesty still lacks the external appearance and manner of an emperor.' In February 1896 he described an incident at a ball where Nicholas waited his turn to ask Princess Yusupov to dance because others stood in the queue before him. Lambsdorff remarked that 'His Majesty goes too far in his modesty.' Not all members of high society were as kindly in their comments. Comparing the appearance of Nicholas II at his coronation with that of his father thirteen years before, Princess Radzivill remarked that, 'there, where a mighty monarch had presented himself to the cheers and acclamations of his subjects, one saw a frail, small, almost insignificant youth, whose Imperial crown seemed to crush him to the ground, and whose helplessness gave an appearance of unreality to the whole scene'. The Minister of War, General Vannovsky, complained that Nicholas 'takes counsel from everyone: with grandparents, aunts, mummy and anyone else; he is young and accedes to the view of the last person to whom he talks'

Petersburg high society was constitutionally incapable of keeping its mouth shut. The Emperor and Empress were surrounded by people only too happy to score off a rival by repeating an incautious or critical remark. It took no time for Petersburg's opinion about the monarch's lack of will or stature to reach the ears of the imperial couple. The main problem was that both Nicholas and Alix were themselves only too well aware of the Tsar's lack of experience and self-confidence. From her very first days in Russia Alix had tried to boost her husband's determination to assert himself. Together with reminders of her and God's love came the call to show who was in charge. As Alexander III lay dying, Alix advised her fiance not to be pushed aside. 'Be firm and make the doctors. . . come alone to you and tell you how they find him, and exactly what they wish him to do, so that you are the first always to know. . . Don't let others be put first and you left out. You are [your] father's dear son and must be told all and be asked about everything. Show your own mind and don't let others forget who you are. Forgive me lovey. '

At the same time as she was attempting to support her husband in his unaccustomed role as Russia's autocrat, Alix was also having to adapt herself to the enormous changes that had taken place in her own life. It helped her greatly that her marriage was, and always remained, very happy. For any young woman, however, the first months of married life can be difficult and few would relish a wedding which occurred one week after their father-in-Iaw's funeral. In Petersburg Alix knew no one. Even her sister Elizabeth, whose husband was Governor-General of Moscow, was seldom in the imperial capital. Nicholas himself was overwhelmed with work and saw little of his wife in the daytime. In the family circle Alix could speak her native English. But outside it, in Petersburg society, Russian or French was necessary. The young Empress had only just begun to learn the former. She was never very happy speaking the latter, which tended to desert her in moments of stress. In the first months of her marriage such moments were plentiful, for as Empress she was forced to be on perpetual show.

Problems quickly arose with her mother-in-law. Because Nicholas's marriage had been arranged so hurriedly, no apartments were available in the Winter Palace or at Tsarskoe Selo until well into 1895. In the interim the young married couple had to live in four rooms in the Empress Marie's palace. Just like Queen Alexandra after Edward VII's death, the Empress Marie stressed her precedence over her son's wife in court ceremonies and hung on to many of the crown jewels, most of which should have gone to her daughter-in-law. Though the two empresses always remained on relatively polite terms they could scarcely have been more different. Alix was much more serious and intelligent but she sadly lacked her mother-in-law's vivacity or her social skills. Living under her mother-in-Iaw's roof, she quickly became aware of the many unfavourable comparisons being drawn between her and Marie in Petersburg society.

The Petersburg aristocracy never liked the young Empress and by 1914 had come to hate her with quite extraordinary venom. Neither Darmstadt nor Queen Victoria were much of a preparation for Petersburg. whose extravagant luxury and low morals shocked AIix. This was a world in which the following conversation could be overheard between two ultra-aristocratic youths: 'Baryatinsky said to Dolgorukov that he is the son of Peter Shuvalov, to which Dolgorukov very calmly answered that by his calculations he is the son of Werder [the former Prussian Minister].' If Alix had been exposed to the world of her uncle the Prince of Wales's Marlborough House set rather than that of his widowed mother. Queen Victoria, all of this might have come as less of a shock. Not even the Prince of Wales's circle, however, could have prepared Alix for the torrent of jealous, malicious gossip that was the hallmark of Petersburg high society.

It was difficult for an outsider to understand or come to terms with the Russian high aristocracy. Like their peers elsewhere, many of Petersburg's grandees were extremely proud. At its best such pride meant a shrinking from the servile flattery common in bureaucratic and, above all, court circles. At its worst it entailed unlimited arrogance and heartbss self-indulgence. Some Russian aristocrats were not averse to remembering that their own families were older than the Romanovs and had participated in successful palace coups in the eighteenth-century 'golden age' of the Russian nobility. Petersburg high society was always elegant and sophisticated. It was often sharp and witty. Of all Europe's nineteenth-century aristocracies, the Russians had produced by far the most renowned literary and musical figures. Even the head of Nicholas II's Personal Chancellery, A.S. Taneev, was quite a well-known composer. Many aristocrats, as we have seen, regarded the last two generations of Romanovs as rather uncouth. Almost uniquely in Europe, Russian aristocrats had no equivalent of a House of Lords through which they could aspire to a political role and enjoy the entertainment, status and glory that such a chamber provided. The aristocracy's civil rights were also not fully secure since the Russian state opened private correspondence and sometimes mistreated even members of the upper classes because of their religious views and activities. For a European aristocracy at the turn of the twentieth century all this seemed a shameful and humiliating relic of barbarism. In addition, by the late nineteenth century agricultural depression and the growth of a powerful state bureaucracy were beginning to push the aristocracy to the margins of Russia's economy, government and society. With rapid industrialization in the 1890s this process speeded up. So too did aristocratic resentment and criticism. The Bavarian diplomat, Count Moy, recalls that the term 'bureaucrat' was the supreme insult in Petersburg high society in the 1890s. The 'easily excited ladies of Petersburg society' were made so angry by reports of police repression that 'a good number of them took the side of the revolutionary elements'. The Empress Marie had lived in Petersburg high society for decades and understood its ways. She shared its love for a constant round of luxurious and extravagant entertainments. But Petersburg's aristocracy was by no means prepared to throw itself at the feet of the shy, aloof and in some ways rather gauche newcomer whose husband inherited the throne in 1894.

The young Empress was ill-equipped by temperament to win this society's loyalty. She danced badly, was extremely shy and loathed large gatherings of strangers, at which she became stiff, cold and silent. Prince Serge Volkonsky, who as Director of the Imperial Theatres met Alix frequently in the 1890s, commented that she

was not affable; sociability was not in her nature. Besides, she was painfully shy. She could only squeeze a word out with difficulty, and her face became suffused with red blotches. This characteristic added to her natural indisposition towards the race of man, and her wholesale mistrust of people, deprived her of the slightest popularity. She was only a name, a walking picture. In her intercourse with others, she seemed only to be performing official duties; she never emitted a congenial spark.

Quite unlike her mother-in-law, who was an expert in smoothing over awkward moments by her warmth and tact, Alix's combination of shyness and obstinacy made her extremely rigid. Even in trivial matters she seemed unwilling or unable to adapt herself to Petersburg society and its ways. Volkonsky recalled that when Nicholas II came to the theatre or ballet alone, he would chatter away amiably. 'But I must add, this was only when he was alone - without the Empress. Alexandra Feodorovna evidently acted as a restraining influence on her husband. She was cold and composed. Her entrances and her exits were in pantomime. She never made an observation or uttered an opinion, or asked a question. '

Alix was proud. She had a high sense of the majesty of her husband's position and of the need to support and maintain it. Knowing only too well Nicholas's natural modesty and shyness, she understood how these were seen as weak and un-imperial qualities by much of Petersburg society. No doubt this accentuated her determination to uphold the monarch's dignity. In addition, however, the Empress was simply an Englishwoman in a very foreign land.

In character Alix was very different to her far more resilient first cousin, Victoria Eugenie of Battenburg, who married King Alfonso XIII of Spain. Nevertheless, as English consorts in very un-English countries, the two women had something in common. In temperament. religion and habits Victoria Eugenie was at variance with the Spanish aristocracy, to whom she always remained an outsider, an Englishwoman. The Queen trod on many Spanish toes. Very much an English princess of the Victorian era, Victoria Eugenie enjoyed organizing charities and involving herself in activities which in Spain had always been the preserve of the Church. Faced with haemophiliac sons, a notoriously unfaithful husband and the harshly critical high society of Madrid, the Queen's very self-discipline, most prized of Victorian royal qualities, gained her 'a reputation of frigidity. She was suspected of being all the things most Spaniards least admired: cold, aloof, insensitive, Anglo-Saxon.' The equally Victorian Empress Alix 'was never able to understand the intricacies of the Russian character, with its suppleness, its Slavic charm, and its languid indifference to what the morrow might bring.' C.S. Gibbes, an Englishman who came to know both the Empress and Russia well, concluded that her unpopularity owed much to 'her want of a "theatrical" sense. The theatrical instinct is so deep in Russian nature that one feels the Russians act their lives rather than live them. This was entirely foreign to the Empress's thought, shaped mostly under the tutelage of her grandmother Queen Victoria. '

A whole series of minor 'scandals' erupted between the Empress and Petersburg society. In 1895, for instance, Alix patronized a charitable bazaar which was allowed to take place in the Ermitage, an unprecedented gesture of imperial goodwill. The resulting discontent was universal: other charities were jealous; shopkeepers complained of unfair competition since the bazaar's goods were untaxed; the director of the Ermitage and the chief of security for the imperial family protested bitterly; and gossips in Petersburg society had a field day. Some of the hostility no doubt reached Alix's ears and the Empress behaved at the bazaar in an even more than normally shy and stiff manner. Nor did Alix win friends by her efforts to inject Victorian earnestness into Petersburg society by setting up sewing circles to make clothes for the poor. The smart set scoffed, the proud kept their distance from anything that might seem like seeking imperial favour, and others complained that the ways of an English vicarage were inappropriate in Russia. Since some of the great ladies who avoided Alix's sewing circles were active in encouraging and marketing peasant handicrafts from the neighbourhood of their estates their criticisms were not always merely selfish or without point.

It is true that in the 1890s the gulf of mutual bitterness and resentment between the Empress and Petersburg society was not nearly as great as in the years after 1905, when it was much increased by the collapse of Alix's health and the arrival on the scene of Rasputin. V.I. Mamantov, who served cheek-by-jowl with the imperial family in Nicholas II's personal suite, recalled that in the 1890s

Her Majesty was different to what age, illness and difficult moral sufferings subsequently made her. . . At that time the Empress still fully enjoyed life . . . Extremely shy with outsiders, and at that time still hampered by imperfect knowledge of Russian, which she later completely mastered, the Empress soon became accustomed to us, who were part of her everyday life, and enchanted us by her friendliness, simplicity and attention. Being very observant and quickly noticing each of our weaknesses, the Empress never lost an opportunity to tease us but she did this very delicately without the slightest wish to offend.

Alix also still had her defenders in high society. Vladimir Lambsdorff, himself a recluse, responded to complaints that the Empress looked bored and ill-at-ease in society by saying that she was evidently a serious woman who had no time for nonsense. General Alexander Kireev commented in his diary that, months before Alix even arrived in Russia, Petersburg society was slandering her and 'already saying that the future Tsarevna has a difficult character'. In January 1896 he added that the young Empress was lovely and sweet but was very easily embarrassed and terribly in need of encouragement to talk. Despite what the idiots of the Petersburg beau monde said, she did not possess a permanently bored expression but was simply very shy. Even by 1900, however, Lambsdorff and Kireev were very much in the minority. Alix always found it much easier to get on with the very old or with children, rather than with people of her own age. At the tum of the century Kireev remarked of Alix's position: 'Poor unfortunate Tsaritsa! Naryshkin says that the young Empress commented that she and the Tsar saw few people. [Naryshkin replied] "Then you both need to see a few more people." Alix answered, "Why? So as to hear still more lies?"

How much Alix's estrangement from Petersburg society actually mattered is debatable. Partly because of this estrangement the imperial couple lived a very isolated life in their suburban palaces of Tsarskoe Selo and Peterhof. Petersburg society was the source of much of the slander that so damaged the dynasty's prestige in the last years before the revolution and much of this slander was rooted in hatred of the Empress. In addition, by distancing himself from Petersburg society Nicholas reduced his circle of acquaintances and the opportunity of drawing on men and opinions different to those he encountered through official channels. None of this would have mattered if the Emperor and Empress had replaced traditional links with the Petersburg aristocracy by forging ties with Dewer Russian elites. By 1900 Petersburg high society was by no means as important as it imagined. The monarchs could justifiably have asked themselves whether leading the capital's social round should absorb so much of their time and energy at a crucial moment in Russian history. The Romanovs' regime was too closely associated with the landowning aristocracy for its own good. It would have been an unequivocally positive move if Nicholas and his wife had tried to build bridges to the new industrial and financial elites of Petersburg and Moscow, some of whose members were not only powerful, but also exceptionally cultured and interesting. Nor were Russia's entire intellectual and cultural elites so radical in sympathy that they would have been immune to all advances from the crown.

Even Wilhelm II had some friends among his country's industrial tycoons. Edward VII got on famously with some of his country's new millionaires and played a role in the forging of the aristocracy and plutocracy into a new upper class. Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria carefully cultivated intellectual and artistic circles in Munich. By accident Nicholas's younger brother, the Gnnd Duke Michael, also mingled in such circles through his marriage to the divorced daughter of a Moscow lawyer, one of whose friends was the composer Rachmaninov. Not surprisingly, Nicholas and his mother were appalled at the news of Michael's marriage, which Marie described as 'another terrible blow . . . so appalling in every way that it nearly kills me'. No European monarch before 1914 would have viewed a son's misalliance in any other way. Nevertheless there ought to have been less dramatic methods by which the monarch and his family could have come into contact with the new Russia that the government's own policies were helping to create.

Nicholas occasionally visited a shipyard. The imperial couple toured the All-Russian Exposition of Trade and Industry in 1896. But old Russia, the world of the Guards officer, the peasant and the priest, was far more congenial to the Emperor and Empress than the milieu of industrialists, financiers or intellectuals. Court etiquette, tradition and lack of imagination also stood in the way. It was impossible to have sensible meetings with representatives of middle-class Russia unless the court's rules were relaxed and opinions could be freely exchanged. The conventions and pecking order of Victorian royalty and the aristocracy had to be disregarded. Nicholas and his wife were too conventional, too afraid to tread on their entourage's toes, to do this. Staying at Sandringham in 1894 the Tsarevich Nicholas was bewildered by the guests of his uncle, the Prince of Wales, who included the Jewish financier, Baron Hirsch. In this company he kept as silent as possible. Conscious of the Romanovs' need to embody the cause of Russian nationhood, Alix tried to get the Almanach de Gotha to drop the words Holstein-Gottorp from the imperial family's name,. Perhaps inevitably, despite their idealization of the Russian peasantry, the world of the Gotha remained a part of Nicholas and Alix's way of life, as did the archaic and intricate rules and conventions which guided the Romanov house and the imperial court. The son of Evgeni Botkin, the imperial family's doctor, commented that although 'the Sovereigns themselves insisted that they valued in people nothing so much as simplicity and sincerity . . . at the same time, without being conscious of It, they actually appraised people almost solely according to the amount of attention these people gave to quite outward and often nonsensical etiquette'. A view of the world partly shaped by the court's etiquette and the pages of the Gotha was inevitably in many respects out of touch with contemporary Russia.

Appropriately enough Nicholas and Alix spent most of their married life in a little town called Tsarskoe Selo, fifteen miles south of Petersburg. The town's name means 'Tsar's Village' and Tsarskoe was indeed a world apart from the rest of Russia. Tsarskoe contained two adjacent imperial palaces. The enormous and superb Catherine Palace was used for parades and other ceremonial occasions. In the smaller but very elegant Alexander Palace the imperial family lived, The interior decoration of the family's apartments was largely English Victorian and was executed according to the Empress's tastes. As Nicholas's cousin, Prince Gavriil Romanov, remarked, 'its style did not at all fit that of the Alexander Palace, which was consistently constructed in style Empire'. in other words on strictly dassicallines.

Nicholas himself, however, loved the family's quarters, On first seeing the newly decorated apartments in September 1895 he wrote to his mother.

our mood . . . changed to utter delight when we settled ourselves into these marvellous rooms: sometimes we simply sit in silence wherever we happen to be and admire the walls, the fireplaces, the furniture... the mauve room is delightful. .. the Wroom is gay and cosy; Alix's first room, the Chippendale drawing-room is also attractive, all in pale green... Twice we went up to the future nursery: here also the rooms are remarkably airy, light and cosy.

The best known room in the private apartments was Alix's boudoir where, particularly as she became older and iller, she spent much of her day. The Empress's loyal friend, Lili Dehn, wrote that the boudoir 'was a lovely room, in which the Empress's partiality for all shades of mauve was apparent. In spring.time and winter the air was fragrant with masses of lilac and lilies of the valley, which were sent daily from the Riviera, , . the furniture was mauve and white, Heppelwaite [sic] in style, and there were various 'cosy corners". On a large table stood many family photographs. that of Queen Victoria occupying the place of honour,' Baroness Buxhoeveden, no less loyal but possessed of rather better taste, commented that Alix liked things more for their associations than for their beauty and that the rooms were, therefore, rather cluttered: 'her's was a sentimental rather than an aesthetic nature'.

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map