Biographies - Alexander I

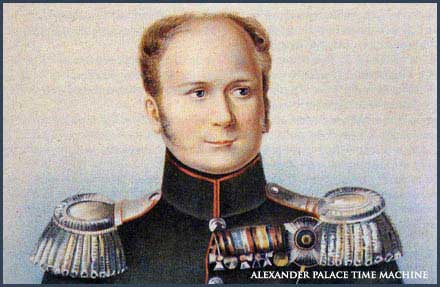

Emperor Alexander I

His parents were Paul, son of Catherine the Great and Maria Fyodorovna, the former Princess of Wurttemburg. At his birth he was taken to be raised by his Grandmother Catherine the Great. Alexander was a blond, handsome and intelligent boy. His childhood was troubled by the divisons in the family. Both sides tried to use him for their own purposes and he was torn emotionally between his grandmother and his father, the Heir to the throne. This taught Alexander, very early on, how to manipulate those who loved him and he came a natural chameleon, changing his views and personality depending on who he was with at the time.

He was tutored by the Swiss republican philosopher, La Harpe, who was personally chosen by Catherine to mold Alexander's personally and give him a broad education. The Empress had no fear of having a future Tsar's education in the hands of a republican, for she knew the strength of the autocracy and the underdeveloped political awareness of Russia at the time. Catherine expected that a liberal education would help Alexander to reign wisely for the benefit of the country. Under La Harpe's tutelage Alexander was well versed in European culture, history and political principals - the young prince became an idealist in the tradition of the Enlightenment - however, La Harpe's focus on theoretical, abstract principals left Alexander without the strength of character and resolve to be a truly effective leader.

Alexander was 17 in 1793 when he married the lovely Elizabeth of Baden, a pretty princess who was only fourteen years old. They were very happy together in the first years of their marriage. Elizabeth looked upon Alexander as her handsome 'prince charming' and he loved her in return. As a wedding present, Catherine gave Alexander the Alexander Palace, showing her preference for his grandson over her son, Paul, by granting Alexander a larger court than his father's. This further poisoned the atmosphere in the family.

Catherine died on November 6, 1796 and her son Paul assumed the throne. He quickly instituted a number of new laws to undermine those aspects of his mother's reign he disagreed with. Paul's actions went much too far, he infuriated the country and especially the nobility. Aristocratic plots were hatched against Paul's life. With the tacit approval of Alexander, the Tsar was murdered at the Mikhailovski Castle in St. Petersburg during the night of March 11, 1801.

Alexander was crowned Tsar to succeed his father. His mother, Maria, refused to speak to her son for a long while, she never entirely forgave him for his complicity in his father's murder. In his first years on the Russian throne, Alexander tried to rule in an enlightened way. The country was very excited at the prospects of Alexander's reign; there were great hopes for the future of Russia and an anticipation of a more liberal form of government and increased freedom. Some went so far as to hope for an end to the institution of serfdom, which sapped the nation of it's energy. At first the Tsar did little to discourage these aspirations. Slowly, for a number of reasons, Alexander turned away from his childhood dreams and principals. Increasingly he found it easier to get results by using the power of autocracy. Once he began using autocratic power, administered through men who served at his will, it corrupted him. The longer he used this method of ruling Russia, the more difficult he bagan for him to return to the principals of good government and the role of the monarch he had learned in his youth.

The war with Napoleon, which ravaged Russia taking hundreds of thousands of lives and destroyed some of the Empire's finest cities, took it's own, personal toll on Alexander. He was troubled by the loss of life and the war itself, which he saw as a not only a battle between nations, but also a spiritual battle between the forces of good and evil. After many battles and setbacks, the victory of the Allies over Napoleon was crowned by a triumphal entry of the triumpant generals into Paris. Alexander rode at their head. He was the apogee of his reign. Instead of resting on his laurels and enjoying the hero status he enjoyed across Europe, Alexander was more and more troubled spiritually. While in western Europe with the Russian Army he sought out and came under the influence of spiritual advisors from foreign countries. He toyed with some of their concepts and ideas, eventually discarding them for the Orthodox faith of his own country. His last years were filled with an obsession with God and Christianity. At the end of his reign he left his Polish mistress of 13 years, Maria Naryshkina, and returned to his wife, Elizabeth, who had suffered from his infidelity and neglect for years. He was a troubled and broken man. One fall he and Elizabeth travelled to the south of Russia. There, on November 19, 1825 in the town of Taganrog, it is claimed to have faked his own death, disappearing to become a monk named Kuzmich, wandering the forests of Siberia for years afterward. The Soviet Government fanned the flames of these rumours when it announced his coffin had been opened in the 1920's and was found to be empty.

Please send your comments on this page and the Time Machine to boba@pallasweb.com

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map