Palace Personalities - 1904 USA Article on the Romanovs

From Bay View Magazine

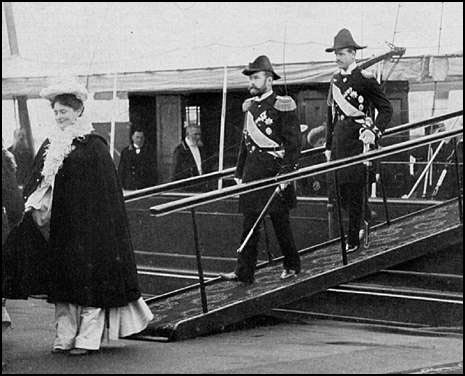

Above: Tsarina, Tsar and Grand Duke Michael; coming down the landing from their yacht in Peterhof. Peterhof, the Russian Windsor, is in the midst of a lovely forest park and lakes, five miles from the capital. It is a frequent comment that in none of the various photographs does the Tsarina look the same, an observation one can verify by comparing her in this picture with her face in others.

Left: The Tsarina in her wedding dress.

Left: The Tsarina in her wedding dress. The tsars of the house of Romanoff undoubtedly possess a powerful personal hold upon the imaginations and affections of the huge population whose titular rulers they are. Beyond the fact that they have been Russia's sovereigns for almost three centuries, history scarcely accounts for their prestige. To say that they have not been a line of strong men is to put the fact mildly. They have not been great warriors or great law-makers. None of them since the first Peter, who died in 1725, has been a great organizer. With one exception they have been identified with no genuine movement for the betterment of their people, and the vast extension of the Russian territory has been no achievement of theirs.

If anything in history is to be called chance, it was chance that raised the Romanoffs to the lofty place they hold. Why the Muscovite boyars, or nobles, in 1613 elected Michael Romanoff to the vacant throne, is one of the puzzles of the Russian annals. Feodor, the last descendant of the Rurik dynasty, which had ruled Russia for seven hundred and twenty years, had died childless. The extinction of the ancient royal house had been followed by anarchy and civil war. The boyars resolved to elect a tsar, and their choice rested on a boy of fifteen, a noble of only secondary rank. Different chroniclers have accounted for the strange choice on various theories. Some attribute it to the good repute of Michael's father, a high official of the church; other historians hold that Michael's name was put forward by certain nobles who hoped to be the real holders of the power nominally placed in the hands of the fatherless boy; while there are others who conjecture that the jealousies of stronger aspirants led to the election of what in American politics is termed a "dark horse." Thus it was that the Romanoffs were borne to the throne on the wave of a great national movement which they had done nothing to arouse.

The family history of the Romanoffs is in striking contrast to that of the Hohenzollerns. They have been short-reigned and short-lived, and their sons have usually been few. There have been sixteen tsars and tsarinas of the dynasty, besides the two Catherines who held the scepter by right of their marriage to Romanoffs. The reigns of these eighteen sovereigns span a period of two hundred and ninety years, an average of only sixteen years to each ruler. Excepting the second Catherine, a Teutonic princess, only one of the eighteen lived to be sixty. Only thrice since Peter the Great, has the crown descended in regular sequence from father to son.

In 1682, near the end of the reign of Charles II in England, and about the middle of Louis XIV's reign in France, Feodor, third of the Romanoff line, died childless, leaving an imbecile brother of fifteen, a ten-year-old half-brother, and a sister, to dispute the succession. It was settled that the two boys, Ivan V and Peter, should be joint tsars, with their sister Sophia as regent; but when Peter carne to manhood, sole power fell into his stronger hands, his brother resigning, and the sister being shut in a convent prison. From this Peter and his peasant wife, Martha Skavronska, the present Ronianoffs are directly descended. Peter was the outstanding personality of his house, the strongest tsar that Russia ever had. He remodeled the whole system of his country's government; he created an army, and though not successful in all his wars, he extended and consolidated his ernpire, securing its recognition as one of the great powers. He built St. Petersburg, "the window by which Russia looks at Europe." He abolished such old Tartar custorns as the seclusion of women and the whipping of debtors, and introduced at least the semblance of many Western institutions. Peter the Great pointed the way to civilization; but his idea of paternal discipline suggests a doubt whether the guide and guardian of his people had himself trodden very far along the path that led away from Asiatic savagery. His only son, the Tsarevitch Alexis, for the offense of criticising his father's political and social innovations, was seized and knouted to, death. The prince's untimely death was officially announced as having been due to an apoplectic stroke, one of those sudden ailments that have been conspicuously common in the medical history of the Romanoffs.

The taking off of Alexis left Peter, at his death, with only one descendant, his grandson Peter, who died childless after a three years' reign, and again there was a contest between claimants who were inere puppets in the hands of rival groups of nobles. The crown went to Anna, Duchess of Courtland, a princess of the elder line, one of the two daughters of the imbecile Ivan V. She, too, died without issue and was succeeded by her sister's infant grandson, who after reigning nominally for a few months as Ivan VI, was deposed by the partisans of Elizabeth, youngest daughter of the great Peter. Elizabeth, who is described by her biographers as "an idle, superstitious woman of lax morals," was another Romanoff to die childless. The crown fell to her sister's son, Peter III, a drunken weakling, who five months later was dethroned by his ambitious German wife, aided by Alexis Orloff and others. The Saxon princess who now came to the throne of Catherine II, was the second Russian sovereign to earn the title of "great." In spite of her foreign birth she thoroughly adopted Muscovite ideas. A strong ruler, successful in war and in diplomacy, she left a greatly enlarged empire to her son Paul.

The new tsar was below the Romanoff average, a tolerably severe statement. After a reign of four years, at first in active warfare against republican France, and then in close alliance with her, he was murdered by nobles who disapproved of his wavering and spendthrift policy. Assassination, it must be remembered, was then and is still the only effective way of voicing political opposition in Russia. Paul's foreign minister, Count Pahlen, one of the murderers, wrote to the British government: "It has pleased the Eternal to call to himself His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor Paul, deceased in the night of the eleventh of this month (March, 1801), by a stroke of apoplexy." The beneficiary of the plot, - to which indeed he is said to have been privy, - was Paul's son, the first Tsar Alexander. Like his father, Alexander was now the bitter enemy and now the sworn friend of Napoleon I. Personally, lie was a benevolent and cultured mystic, who regarded himself as a special envoy of the Almighty, and who talked alternately of his desire to resign the intolerable burden of a crown, and of the sacred duty of suppressing liberal ideas throughout the world, for which purpose he organized the Holy Alliance.

In 1825 Alexander I died childless; his brother, Constantine, refused the crown, and Paul's third son, Nicholas, took it at the cost of suppressing a futile insurrection. His reign of thirty years was successful until it ended with the Crimean War, a costly blunder for France and Britain, a disaster for Russia. The sting of defeat helped to cause Nicholas' sudden death, which brought to the throne his son, Alexander II. The second Alexander, the one Romanoff tsar who had both liberal views and personal strength to enforce them, is immortalized as the emancipator of the serfs from their bondage to the soil. Had he lived only a few more days, perhaps even a few more hours, he might have won a still grander fame and done a much more important service to his country. There is good reason to believe that on the very afternoon of his terrible death by a nihilist's bomb, he was about to sign a ukase giving Russia a constitutional government. The full bearing of so tremendous a reform can scarcely be estimated. It belongs to the vague realm of the "might have been," but it is safe to say that it must have begun a wholly new and better era for the great empire and her people.

It is understood that Alexander III, son and successor of the murdered tsar, brought his father's edict before the next meeting of the councillors, expressed his intention of signing it, and secured their approval; but before the momentous document could be promulgated, the reactionary Pobyedonosteff persuaded him to suppress it. And never since has Russia had a statesman like Louis Melikoff, the enlightened mentor of Alexander II.

The two latest emperors have at least added nothing evil to the record of the Romanoffs; nor, on the other hand, beyond the bettered moral tone they have given their court, have they added anything markedly good. Nicholas II, who is now tsar of all the Russians, was born at St. Petersburg, May 18, 1868, and was the eldest son of Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna, farmerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark. Nicholas received the education ordinarily given to grand dukes, and a certain amount of military training. In 1891 he made an extended tour through Asia, and while in Japan narrowly escaped assassination at the hands of a Japanese maniac. At his father's death on Nov. 1, 1894, he became tsar. In November of that year he married Princess Alix of Hesse-Darmstadt, and in May, 1896, they were proclaimed sovereigns with a brilliant coronation ceremony. The new tsar assured his people that his policy would be peaceful, and as far as Europe is concerned, his policy has been carried out. The most notable act of his administration was the peace rescript of 1898, which resulted in The Hague Peace Conference. Some of the ablest statesmen of Russia are in his service, and it is, therefore, difficult to determine just what he has personally accomplished for Russia.

From various contributors to recent periodicals, the following sketch of the Tsar and Tsarina of Russia has been gleaned:

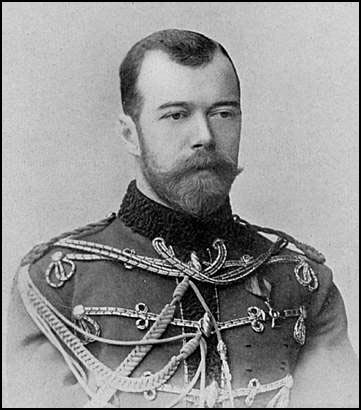

Above: Nicholas II, latest and finest of all of the photographs of the Tsar.

Nicholas II is a curious contrast to his father both in appearance and in character and disposition. He has no love for pomp and ceremony. When his father drove about the capital, he bad the streets lined with troops and drove in a splendid equipage surrounded by guards and attendants. But the present Tsar gives no notice of his drives and is fond of going alone with the Tsarina and with a small attendance. Under his regime the court etiquette has become much less strict, and all his subjects may be admitted to his presence. Peasants will travel hundreds of miles to present their petitions to him, assured that the Tsar will grant them an audience.

Nicholas II is grave in public but in private is full of fun and very fond of joking with the members of his intimate circle. The stories that have been published as to his brooding melancholy and incipient insanity are said to be pure inventions of the press. That he has moods of depression is probable, for he is human, and the task which lies before him is one from which the stoutest heart might well shrink appalled. The solemn oaths of the coronation are sacred in his eyes, and he has conscientiously endeavored to fulfill them. He has selected his ministers of state with great wisdom, and is striving to guide Russia to greater things.

It is said that many of the Tsar's most highly commended acts have been prompted by his lovely wife, who is a true helpmate in every sense of the word. The look of settled melancholy on the face of the Tsarina has lead many to suppose the marriage is an unhappy one. But those who write of the home life of the imperial family assure us that the marriage was one of love. The Tsar's affection for his wife dates from the time when she was a child of twelve, and they met at the Grand Duchess Serge's wedding. She was twenty-two when the subject of marriage was broached and at first she opposed it, but an enormous pressure was brought to bear on every side and she finally yielded her consent. It meant closer relations with Germany and England, and a woman of royal blood must consider political advantages. At first her grandmother, Queen Victoria, with-held her consent to the marriage on the ground that Princess Alix was too young and too delicate for the anxieties and responsibilities of a Russian throne. The necessary change of religion made Princess Alix waver again and again in her decision. She clung to the evangelical faith in which she had been brought up, while as tsarina she must be a member of the Greek Orthodox Church. Teachers were sent from Russia to instruct her in the Greek faith, and at last she consented to marry the coming Tsar. She has discharged the duties of her position with even a stronger sense of duty than her predecessor, the Dowager Tsarina Dagmar, and has the good of her empire at heart. She is a woman of cool judgment and her advice is always good and well-balanced. She takes life seriously, but is always cheerful and amiable. One of her most earnest endeavors has been to ameliorate the lot of the women of the poorer classes.

Right: Tsarina Alexandra in the uniform of her Uhlan regiment.

Unfortunately the Tsarina is very reserved and extremely sensitive. In the midst of a court circle she is ill at ease and apt to relapse into silence. She has not the abandon or familiarity characteristic of the Russians. They do not deny her charm, her beauty, her virtues, her many talents, but they do not like to be kept at a distance. But an empress who has no sons is even worse than an empress who is silent and distant among the courtiers. Her first four children were all daughters, and the nation was greatly disappointed that the Tsar had no son and heir. But the recent birth of an heir to the Russian throne is regarded by the people as a mark of divine favor, and the Tsarina is no longer looked upon with displeasure. The Tsar and Tsarina are devoted to their four sweet little daughters and love them as dearly as if they had been heirs to the crown. When the little Grand Duchess Olga was born, the Tsar is reported to have said: "I am glad the child is a girl; had it been a boy he would have belonged to the people; being a girl, she belongs to us."

The Tsar has many palaces, but those lie most frequently occupies are the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Peterhof, and Tsarskoye Selo in the suburbs of the city, and Livadia in the Crimea. The favorite sojourning place of the imperial family is at Tsarskoye Selo where they have a simple quiet life apart from the wearisome routine of court functions. Though the Tsar and Tsarina of Russia are the richest sovereigns in the world they are very simple in their tastes. The Tsarina used to be almost puritanical in her ideas of dress, and even now she despises showy attire.

Although she has wonderful pearls, starsapphires, and Cabachon rubies, she seldom wears jewels, and the royal pair set no extravagant fashions for their people.

The languages used by the Tsar and Tsarina in their private life are English and German, though they speak also French and Italian. The Tsarina did not learn Russian until after her betrothal, and though she has a good accent she speaks it very slowly. The eldest child, Olga, born in 1895, can converse fluently in English and French, as well as in Russian. The second daughter, Tatiana, made her appearance in 1897. The bestowal of this name upon her delighted the Russian people, for it has from time immemorial been a favorite name among the middle and working classes, but had never been borne by a member df the imperial family. The Grand Duchesses Anastasia and Maria, with Baby Alexis, born August 12, 1904, complete the family group.

The Tsar's eldest brother George, until his death five years ago, was heir to the throne. Since then and until the recent birth in the imperial family, Prince Michael, a young man of twenty-four and a soldier, has been the heir. The younger children with their mother, the Dowager Tsarina, used to spend much of their time in England, the Riviera, Germany, and Denmark. Among the members of the court are many who sigh for the times. when Maria Feodorovna was the tsarina because she cherished all the tradition of court ceremonials, but most of the Russian people prefer the simple, democratic manners of the present Tsar and Tsarina, and the unostentatious life of the royal pair commends itself strongly to the masses."

Please send your comments on this page and the Time Machine to boba@pallasweb.com

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map