Palace Personalities - God in All Things - the Religious Beliefs of Russia's Last Empress

by Janet Ashton

“God in all things”: the religious beliefs of Russia’s last empress and their personal and political context.

In his beautiful account of his stay in St Petersburg in 1991 Duncan Fallowell describes the mental picture evoked by the frantic finale of Scriabin’s Song of ecstasy: ‘….the Tsaritsa lays out the cards on the ebony tarot table in the Winter Palace while outside the snow falls softly and ceaselessly through the night. She longs for Rasputin but he is gambling in a casino over the bridge and does not come…’[1]

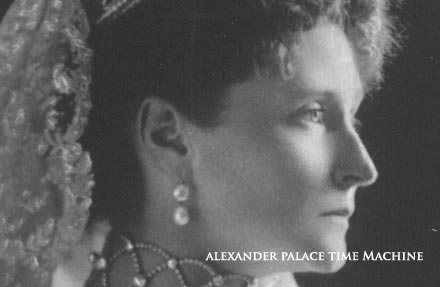

This is one of the most enduring popular images of Aleksandra Feodorovna, the last Empress of Russia: a table-tilting hysteric, the epitome of the decadence and neurosis of upper-class Edwardian Russia. Deriving from the more purple contemporary accounts of the fall of Tsarist Russia, it vies with the image of the sad-eyed lilac lady, the deceived victim of manipulation and circumstance favoured by her friends and sympathizers to present unbalanced and unenlightening pictures of an important figure and of the religious or spiritual interests that drove her.

Christianity lay at the core of Aleksandra’s mental world and of her personal life, and was a live political factor in her husband’s reign – both as the motivation for the popular movements of the extreme right and as the justification for Nicholas II’s and Aleksandra’s view of their own role. I have long been interested in her religious views, but curiously enough one of the prime keys in unlocking these for me has been a set of manuscript letters here in the British Library. These letters, from Aleksandra to the English Bishop William Boyd-Carpenter, have been cited in part just once previously in a journal article - by the American historian Robert Nichols, who used them to illuminate the Empress’s thinking around the time that she became interested in popular saints and mass spirituality [2]. I have found them more broadly enlightening. Reading them in conjunction with references in notebooks and letters and the odd comment in the memoirs of her franker friends has allowed me to build up a fairly full picture of the origin, context and influence of the Empress’s religious views.

Religion and her private life

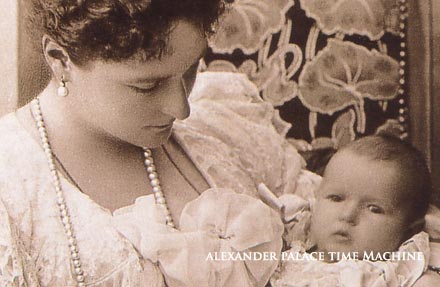

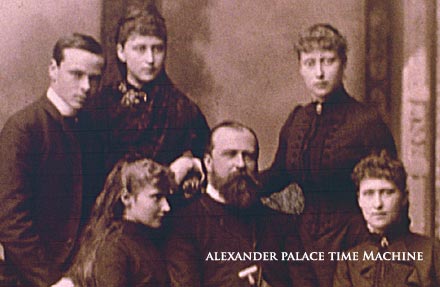

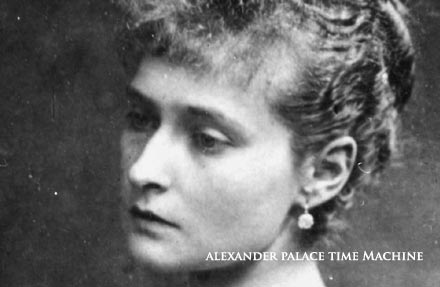

The last Russian Empress was born and baptised into the Lutheran church in Darmstadt in1872. Originally christened Alix, she was the youngest surviving child of Queen Victoria’s daughter Alice and Grand Duke Louis IV of the German state of Hesse and by Rhine. It’s an arguable proposition that the death in childhood of the brother and sister closest to her in age, as well as of her mother when she was six, increased her tendency to introspection. In contemporary idiom, Alix was something of a control freak, who clung tenaciously to what was important to her in constant dread of losing it too. She lacked lightness of spirit and never was to find life very easy to cope with.

As a teenager she met her future husband, then Heir to the Russian throne, and the attraction was genuine and mutual, as well as unpopular with Nicholas’s parents who sought a bigger catch. At some point it became clear to Alix that in order to marry him she would need to adopt his Orthodox religion, and her reluctance to do so was spelt out in the first open letter she wrote him about him her own feelings.

‘I have tried to look at it in every light possible, but I always return to one thing. I cannot do it against my conscience. You, dear Nicky, who also have such a strong belief will understand me.’[3]

Five months later he managed to persuade her to change her mind. Several other Protestant princesses who had renounced their faith when they married Russian Grand Dukes were involved, and it is usually assumed that in talking to her they emphasised the doctrinal similarities between Protestantism and Orthodoxy. Robert Nichols believes that the Pietism popular in the German courts such as the one where Alix grew up may have assisted them in their task. Pietism tends to emphasise a personal spiritual connection with God that over-rides considerations of dogma and creed. [4].

Nicholas himself was affected by and interested in other religions and their possible similarities to his own. In particular he was drawn to Buddhism, with its various traditions of semi-divine monarchs reincarnated from the Buddha. In 1891 while visiting Siam as part of a ‘grand tour’ to complete his education he recorded in his diary that,

‘Each time I see a temple distinguished by grandeur, order and reverence, as in Russia, as I enter I begin to feel a religious mood, as if I am in a Christian church!’ [5]

Alix is often said - once her decision was taken - to have hurled herself into the Orthodox Church with the immoderate zeal of many converts. Certainly she came to embrace the Church wholeheartedly, and to observe all of its practices with an ardour that embarrassed many of her contemporaries. And yet her progress to this point was in fact rather a slow and measured one.

She was formally converted – taking the name and patronymic Aleksandra Feodorovna – in November 1894, just days before her wedding. This was a time of great spiritual torment for both Alix and Nicholas, hurled onto the throne by the sudden and early death of his father. He found much of his time absorbed by ministers, visitors and affairs of state. She sat alone in the rooms they shared studying Russian and writing to friends with descriptions of her alternating happiness and sorrow.

In early 1895 she wrote to William Boyd-Carpenter, who as Bishop of Ripon who was also court chaplain to her grandmother Queen Victoria, that she was trying hard to come to terms with external trappings of her new faith. ‘Now that I am more used to hear the Russian language I can understand the service so much better, and many things have become clear to me and comprehensible which at first rather startled me. The singing is most beautiful and edifying, only I miss the sermons, which are never preached in the Imperial chapels…..I saw by the papers that you had been at Osborne, and wish I could have heard your sermon. I have often read through the one you so kindly gave me, and each time it did me good.’[6] Her choice of confidant is, I think, very illuminating. Boyd-Carpenter was a mystic, in the sense that his relationship with God was personal and ongoing and extensively documented in the diaries and notebooks in which he constantly examined his own ethics and appealed directly to his creator for help and guidance. [7].

I should take a moment to define ‘mystic’, since misunderstandings over the meaning of this label – often and with justification attached to Aleksandra herself - are probably behind some of the wilder legends about her religious beliefs. The psychologist William James – the most influential writer on religious topics of Aleksandra’s generation – puts this into a nutshell: ‘The words mysticism and mystical are often used as terms of mere reproach, to throw at any opinion which we regard as vague and vast and sentimental, and without any basis in either facts or logic. For some writers a mystic is any person who believes in thought-transference, or spirit return. Employed in this way the word has little value.’ He then proceeds to describe the mystical state as precisely one which defies transmission to anyone else, either verbally or in any other way. ‘They are states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect.’[8]. Mystical experience has nothing to do with seances or any other such thing, but is a state of brief and intensely personal inner understanding of God arrived at largely through prayer and contemplation.

With Boyd Carpenter, mystical self-examination was more than simply an expression of conscience and faith; it was a necessity. Born in 1841, he was in some ways the classic product of a ‘muscular’ Victorian Christian education. He studied mathematics at Cambridge, and his interests as a student were sport and socialising rather than profound theological questions. As a clergyman, he was renowned for his gripping sermons, full of references to literature and everyday life. ‘The Bishop…by his preaching,’ wrote his student and biographer H.D.A. Major. ‘[gave] educated laymen the luminous impression that Christianity is essentially rational, moral, and spiritual : that it is in the highest and best sense world-embracing, not world-renouncing.’ [9] His family background was evangelical; he believed in service and self-sacrifice. All this was fairly standard Victorian Anglicanism, and it had shaped Alix of Hesse as strongly as it had many of her relatives.

But Carpenter was more marked by the intellectual upheavals in the world of his adolescence than he may have realised until many years afterwards. The publication in 1855 of Darwin’s Origin of species shook many peoples’ faith in the teachings of the Bible. Eighteenth-century rationalism had attacked the existence of God from a logical and philosophical perspective, but Darwin’s scientific evidence was more accessible and had a more profound affect upon both the layman and the church. In 1871 the theologian David Strauss published his massively controversial Life of Jesus, which also questioned the literal truth of many Biblical passages. He dedicated the book to his patron and pupil, Queen Victoria’s second daughter Princess Alice – the mother of Alix of Hesse.

Alice was condemned at the time (erroneously) as ‘an absolute atheist’, but before the end of the century a mainstream figure, Boyd-Carpenter himself, would argue that accepting the literal truth of certain parts of the Bible was not the be-all and end-all of Christianity. ‘I am ready to admit that in the history of Christendom there has been a tendency to…speak as though salvation came to the man who rests only on the belief in certain historic facts or theological propositions; but this is foreign to the primitive spiritual realisation.’[10] ‘The New Testament gives to us the picture of Christ without; the religious conscience of Christendom bears witness to the Christ within…it is not Proof, if you will; it does not banish all questions; it does not solve all difficulties; but it is the drawing together of two facts which are enough to evidence the presence of a great religious power in the world….surely there is enough moral power in this Christ of fact and experience to make Him a good working hypothesis of life and conduct.’ [11]. Boyd-Carpenter affirmed the supreme importance of internal personal experience of Christ, and the daughters of the troubled Princess Alice have left evidence that they found this helpful in their own religious thinking. Several of them – including Aleksandra herself – were very interested in science, and when in 1902 Boyd Carpenter gave his own book of thoughts on the Bible to Aleksandra’s sister Irène, the latter wrote happily to him of how helpful she had found it in terms that suggest she too had been affected by this interest: ‘I shall never forget the shock I got when still very young when someone said to me that the Bible was a book one could not go by…and I felt so helpless to find an answer.’[12]

Boyd-Carpenter, this wordly mystic of a bishop, corresponded widely with royalty, above all with the many descendants of the Queen he served. Even his biographer makes a wry reference to the ‘nice life’ of a Victorian bishop, running between parties and dinners and whispering into the ear of the monarch. But the overwhelming subject matter of the letters is religious and the tone intimate and informal: royalty here goes by its nicknames because he knew them all so well.[13]

Later, in 1913, the Empress Aleksandra was to share details of a near-fatal illness in her son which was infamously kept from the majority of people outside the family, even those in daily contact with them: ‘We trust before long to see him on his legs again running about. It was a terrible time we went through, and to see his fearful suffering was heartrending - but he was of an angelical patience and never complained at being ill - he would only make the sign of the cross and beg God to help him, groaning and moaning from pain’ [14]

As a wife in the first year of marriage, her husband taken up with the duties of the throne, the new Orthodox Empress Aleksandra Feodorovna comforted herself by reading a sermon that this Anglican Bishop had given her at Windsor during her engagement. She alluded to it in her letters to him for years to come. [15] Then as the children began to arrive, it was to another Protestant whose writings she turned; those of an American Presbyterian minister called James Russell Miller.

To the end of her life she kept notebooks full of jottings from poets, philosophers and theologians, full of conventional piety and goodness that underscored the “correctness” of her actions. Her letters to Boyd-Carpenter and to other occasional correspondents have quite a different tone from the private correspondence with her husband and friends. They are prim, polite, often rather wistful (not to say cloying); very different from the woman who could write of a minister she disliked, ‘I longed to fling my fury into his face!’ and whose intimate letters are alive with irony and emotional frankness and are even occasionally downright spiteful. Aleksandra struggled all her life against her own perceived bad behaviour and lack of faith. To her immediate family she was anything but the paragon of piety some of her friends and sympathisers suggest. In 1919, her eldest sister Victoria would write of the imprisonment and murder of her two ‘Russian’ sisters, ‘[Ella’s] wonderful faith will have upheld and sustained her in all she has gone through, so that the misery poor Alix will have suffered will not have touched Ella’s soul.’[16]

Aleksandra had been raised in the Victorian tradition of service and self-abnegation: her father was a soldier, her mother a tireless founder of hospitals and womens’ training colleges. When their mother died, Alix’s eldest sister Victoria had taken on her role as guide to the younger children and head of domestic arrangements, and when Victoria became engaged many relatives were astonished. ‘I thought she would not have married at all – nor would she if she had had to leave her poor Father,’ [17] commented her grandmother and namesake the Queen.

With this background, it is not fanciful to suggest that Aleksandra felt almost guilty at the pleasure she took in her family life, and that she sought in Miller reassurance that this pleasure was more than simply selfish. During their engagement she wrote to Nicholas – albeit not entirely seriously, ‘I am selfish and greedy and want the best things for myself – shocking, is it not?…Me want you, and only for me. You see how greedy I am.’[18] Later though she would copy from Miller: ‘We are made for love – not only to love but be loved……each must forget self in devotion to the other’[19]

Religion and the role of an empress

There is much in Miller about service and helping others. ‘Our Lord gave us the full truth when he said of His own mission that He came “not to be ministered unto, but to minister”…Love seeks to give, to minister, to be of use, to do good to others.’[20] Aleksandra sought to practice his instructions in the public as much as the private sphere. She feared the social obligations that had traditionally been the obligation of the women of the Russian Imperial family, lacking the charm and easy conversation to make a success of them. Her administrative and charitable work, however, was the successful and perhaps more symbolically relevant side of her role as a twentieth-century consort. She established – and tirelessly visited – sanatoria for tuberculosis patients in the Crimea; she held bazaars to raise money for them; she endowed schools in her name and her childrens’ from their private funds. As often noted, she served as a nurse during World War One. What is less often remembered is that she also took the organisation of the entire hospital system for St Petersburg under her wing so that by 1915 she was patron of 85. [21] Her sister Irène underlined the religious inspiration of this charity work by writing to tell Boyd-Carpenter about it: ‘Alix goes almost daily to a hospital in the Park in Zarskoe where she even reads to the poor soldiers in Russian – she has a school for them where they do basketwork, and tailoring, and carpentering and boot-making…Then a newly-founded hospital for Babies where nurses are trained for nursery work…also answers well….then her two trains are still running for the sick and wounded in Siberia – and her depot of clothing and necessaries still greatly in demand.’[22]

Aleksandra was following the example her mother had set in defining the role of modern princess almost as vicar’s wife writ large. Patronising charities and undertaking committee work in the Victorian style were to become the raison d’être for the British royal family as the twentieth century advanced and its real power declined. Aleksandra like her more effective and remarkable mother anticipated this to a degree, but in Russia at that date such behaviour was unappreciated. She was openly mocked by members of the aristocracy for what they saw as hopelessly provincial behaviour – not because they lacked charitable impulses themselves, but because of the self-righteously obvious and personal ways in which she went about it. It was a formulaic role that rather lacked depth.

Their wedding itself apart, the single most important religious event of Aleksandra’s early married life was of course her own and Nicholas’s coronation. It took place in Moscow on May 26th 1896, when they had been married for just over a year. The Emperor and Empress spent a considerable amount of time praying in retreat before the service, and the ceremony was charged with symbolism concerning the relationship between the Emperor, God, the Church and the country. Nicholas and Aleksandra appear to have taken a lot of it literally.

Unlike the majority or European monarchs, the Emperor crowned himself, an act which theoretically underlined his status both as a priest within the Church and as autocrat by Divine Right, the rightful interpreter of God’s will on earth and the source of both civil and spiritual law. In the ideology of the Russian monarchy, there would be no obvious division between the civil and the spiritual, the church and the state. (Crowning in this manner actually dates back no further than Peter the Great, the least spiritual of Orthodox monarchs, and could alternatively be seen to emphasise the monarch’s or the state’s primacy over the church.) The words of the coronation oath re-emphasised the Divine and unassailable origin of his power, describing him as ‘chosen’ to be ‘Tsar and judge over the people’.[23]

This idea is one which had naturally been encouraged by the Church for century on century, ever conscious of the debt it owed those powerful monarchs of history who had driven the Tartars from Russia and resisted the re-unification of Orthodox and Catholic churches. Hand in hand with it marches the famous conception of Russia as a sort of chosen land and Russians as followers of the only true faith whose historic capital Moscow – in which the Emperors continued to be crowned even after St Petersburg had replaced it as the centre of political power – was destined to become the ‘Third Rome.’[24]

In the late nineteenth century the pan-Slav and other far-right movements were deeply interested in all of this; these medieval myths were significant factors in the political climate of Nicholas’s reign. Behind the forced russification and Orthodox-ization - of the Empire’s non-Russian provinces such as Finland and Poland lay a brutal political pragmatism on the one hand, but also on the other a sense of innate superiority based on language and religion. Religion and religious myths were being used to underpin the overwhelming power of the imperial state.

Nicholas and Aleksandra were rather too aware of their own foreign ancestry to swallow the nationalist agenda uncritically, but they were well aware of its importance in shaping Russia’s perception of herself. Nicholas’s first choice for the coronation crown, for example, had been the Cap of Monomakh rather than the enormous crown of Catherine the Great used by his immediate forebears. [25] The fact that the Cap weighed only two pounds may have been a consideration, but of no less significance is the fact that Vladimir Monomakh had received his own regalia from the Byzantine Emperor Constantine, who is said to have exhorted him to use them, ‘…oh god-loving and pious prince….for your glory and honour and for your enthronement over your free and autocratic Tsardom….thus the Church of God will be trouble-free, and all orthodoxy will be at peace…for you shall be called, henceforth, God-crowned Tsar, crowned with this imperial diadem.’[26] Nicholas’s attachment to Monomakh’s Cap can therefore be seen as another element in his mystic conception of his own role as autocrat without whom the nation would not exist at all, and legitimate inheritor of the Byzantine system of government which claims, as a recent writer put it, to ‘place Christ at its head’.[27]. In short, the coronation implied to Nicholas the inextricable popular identification of Russia, autocracy and Orthodoxy, and his wife absorbed this too, using religious justifications to underpin her faith in a political system that elevated her husband to a semi-divine role. What a psychologist would make of this can only be conjectured!

Merging the personal and the political

Aleksandra’s interest in the Orthodox Church developed to extend to every aspect of its teaching and observance. She was primarily interested in its philosophy; as a former Lutheran she had to put this first. But alongside all that came external observance, which to the Orthodox is a manifestation of inner faith. In Orthodoxy, there is no separation between the body and the spirit, so external observance can never be taken lightly. Nicholas and Aleksandra fasted; they took Communion – and asked forgiveness of one another – frequently[28] ; they exhibited clear faith in the Orthodox doctrine of perpetual prayer. Writing to his mother about his son’s near-death from haemophilic bleeding in 1912, Nicholas noted the child’s constant agonised repetition of the phrase,

‘Lord have mercy on me, Lord have mercy on me!’ This is the Jesus prayer, which the most pious mystics constantly intone, and whose importance had apparently already been impressed upon the suffering eight-year-old – though in his pain it probably came naturally to the poor child anyway.[29] ‘In the Orthodox Church,’ Aleksandra wrote to Boyd-Carpenter, ‘one gives children Holy Communion, so twice we let him have that joy, and the poor thin little face with its big suffering eyes lit up with blessed happiness as the Priest approached him with the Sacrament. It was such comfort to us all and we too had the same joy - without trust and faith implicit in God Almighty's great wisdom and ineffable love, one could not bear the heavy crosses sent one’ [30]

The boy, Aleksei, took his religious observance rather more lightly when well. Nevertheless, he and his four sisters were given an education in which Christianity received an emphasis even greater than that in most Edwardian childrens’ lives. ‘May God help us to give them a good and sound education and make them above all good little Christian soldiers fighting for our Saviour,’ the Empress wrote to Boyd-Carpenter [31]. They learned their charitable obligations at sanatoria and fund-raising bazaars when very young and were taken to church almost daily. When apart from them, Alexandra wrote to remind them of their prayers and to pass on snippets of advice about behaviour from their ‘Friend’ Rasputin [32]. Their return letters might be found lightly signed in the Orthodox manner, ‘servant of God Nastasia’. [33] This has an odd tone coming at the end of descriptions of siblings’ squabbles and taunts, and the tutors of at least one of these children felt that her own extreme preoccupation with religion was merely a case of going through the motions to please her parents. [34]

Yet there was a lighter side to religious observance. Neither Nicholas nor Aleksandra was too prim to laugh when untoward incidents occurred in church, and levity on religious topics extended as far as sexual innuendo; on one occasion Nicholas wrote to urge his wife to, ‘sleep well, dream gently – but not about Catholic priests!’ [35]

As this all suggests, Aleksandra’s personal faith was more than the conventional Victorian observation of piety that marked her public preoccupation with charity work. She developed her own strong ideas on aspects of religious belief and doctrine, and she was prepared to cherry-pick the Church’s history and teachings to find justification for her own opinions. She additionally sought further justifications through her own readings for accepting what it was asking her to do.

The Empress’s interest in religious texts that dealt not just with religious practice and a Christian lifestyle but with the very nature of God appears to have developed with her friendship with the Grand Duchess Militsa, one of the better-educated members of the imperial family, who learned Farsi in order to study Persian mystic texts in the original. Aleksandra read these eastern texts too in translation and adopted as a personal symbol the ancient indic sign of the swastika, symbolizing life and regeneration. The focus of her reading seems to have been the all-pervasive presence of God: there is no reason to think that Aleksandra actually considered leaving the Church, and indeed the entire thrust of her thinking was to find universal expressions of faith, the similarity rather than differences between religions.

In 1903 she wrote to Boyd-Carpenter that she was reading Jakob Boehme and ‘the sixteenth and seventeenth century Dutch theosophists’.[36] This was an interest that many in the ‘esoteric’ circles to which Aleksandra is often assumed to have belonged would have recognised. Boehme was popular with people who dabbled in the tarot, spiritualism and astrology, not least because he larded his own work with (metaphorical) references to alchemy and the position of the stars. He has also however had a huge influence upon Christian thinking, particularly the puritanical Protestant sects and to a lesser degree the Russian Orthodox Church. It is most unlikely that Alexandra would have mentioned him to Boyd-Carpenter had her interest in him been anything other than Christian and wholly in line with seeking personal experience of God. There’s evidence that she may briefly have taken some interest in spiritualism, but if so, she was unimpressed: ‘I consider it a very a great sin to attempt to disturb the spirits of the dead, even supposing that such a thing were possible,’ she told a friend on one occasion. [37]

Jacob Boehme (1575-1624) was a shoemaker from Gorlitz in what is now eastern Germany. He had a large circle of educated friends and he traveled widely on business at a time when Europe was in a state of extreme religious ferment. There is some evidence that he was influenced in his thinking by radical Protestants such as the Hussites, the Anabaptists and the Moravian Brotherhood, and by people in contact with near-Eastern mystics. The central themes of his large and complex body of work are the birth of God and man’s knowledge of and relationship to Him.

Boehme was sporadically though not particularly harshly persecuted by the established church for his teachings, but they took root fast. He was especially popular in Holland and England, but within a century of his death a couple of his disciples had already set their sights on Russia. The activities of the earliest Behmenist missionaries there attracted the attention of Peter the Great and duly got some of them executed as heretics. [38]

‘For though I seek one to speak, teach and preach and write of God, and though I hear and read the same, yet this is not sufficient for me to understand him; but if his sound and spirit out of his signature and similitude enter into my own similitude, and imprint his similitude into mine, then I may understand him really and fundamentally, be it either spoken or written, if he has the hammer that can strike my bell,’[39] wrote Boehme of his search for understanding. He believed that good and evil were both equally present in God and man, and that it was partially due to environment which came to the fore and became dominant in an individual. ‘We then see that an evil man is often moved by a good man to repent of and cease from his iniquity, when the good man touches and strikes his hidden instrument with his meek and loving spirit…..in like manner how a good man corrupts among evil company’[40] Passages like these can be read as a reconfirmation of the doctrines Aleksandra had been taught from infancy: help people; seek knowledge of God and then use what you have learnt to go out into the world and do good. This sentiment could be read as a simple call to Christian charity, but it also increasingly as Robert Nichols has written, had political repercussions.

Nicholas and Aleksandra both saw their role as monarchs in religious terms. Since he believed that he held Russia on trust from God, Nicholas felt himself personally accountable to Him for the welfare of the Empire. ‘In the sight of my Maker I have to carry the burden of a terrible responsibility, and at all times be ready to render an account to Him of my actions. I must always keep firmly to my convictions and follow the dictates of my conscience.’[41] Thus he explained himself to his mother. That he was with this statement justifying to her his support for an aggressively ‘russifying’ policy in Finland says much about the conflation of righteousness and nationality in Nicholas’s mind.

Aleksandra was obsessed in the end with the symbolic importance of his coronation: ‘God anointed you at your coronation, he placed you where you stand, and you have done your duty, be sure, quite sure of that,’ she told him on one occasion.[42] The relationship between Russian Emperor, God and Church was profoundly studied, both then and now, and clearly influenced Nicholas and Aleksandra’s conception of their role even at the dawn of the twentieth century. The ancient Byzantine tradition of symphonic relations between church and state, with the Emperor attending ecumenical councils and pronouncing on religious matters, had been broken down gradually by successive Romanov Tsars, culminating in Peter the Great’s abolition of the Moscow Patriarchate and placing of the church beneath effective state control. Nevertheless, elements within the Orthodox Church – in particular the Russian Orthodox Church outside Russia - still insist that as late as Nicholas’s reign the relationship between the Russian autocrat and his church was different to strict church-state division leading to fraught power struggles that had existed between western despots and the Pope:

‘In Orthodox Russia there existed a society composed…of “government and priesthood” – a holy commonwealth. The Tsar was never placed outside the Church or above the law, but always within the Church and subject to the law of Christ. He was very much the servant of the Gospel: he was required to live by it and rule by it in order to be worthy of the blessings of God upon himself, his family, and his nation.’[43] Even if others acknowledged that it no longer existed – if it ever truly had - the necessity for returning to this sort of relationship was a crucial plank in nationalist thinking, and Nicholas and Aleksandra believed it too on moral and historical grounds. At one point in his reign, Nicholas was to consider re-establishing the Patriarchate. Aleksandra’s growing obsession with her husband’s saintliness was more than simply a reverence for his character: it is an idea specifically encouraged by the Church and by the nationalist myth (dating from no earlier than the nineteenth century) of the Tsar as the pinnacle and guardian of Holy Russia, sviataia rus. The Orthodox Church has a long tradition of canonizing its monarchs and princes that starts with Vladimir of Kiev and ends with Nicholas and Aleksandra themselves.

He accepted his role rather passively; she added a more aggressively crusading role, which she apparently extrapolated from her reading of Boehme and of Russian mystics influenced by him. She saw the monarch’s role as bringing the nation to God, and she and Nicholas both sought assistance in this role from others in whose goodness they believed and which they thought would reflect upon those around them and compensate for their own shortcomings. ‘A country where a man of God helps the sovereign will never be lost,’ she later wrote of Rasputin. ‘God opens everything to him, that is why people who do not grasp his soul immensely admire his wonderful brain, ready to understand anything…he will be less mistaken in people than we are; experience in life blessed by God.’[44]

Her belief in such guides was founded on a form of populism too. Boehme’s mysticism was profoundly opposed to sectarianism and clerical dogmatism, and this must have appealed to Alexandra in a number of ways. ‘Men contend or controvert much about the shell and outside of knowledge and religion but regard not the precious sap of love and faith which serveth and availeth to life…a real true Christian hath no controversy or contention with anyone’ her philosopher wrote[45]. Useful words for one had agonised so long over the differences between the Protestant and Orthodox churches; but also appealing words to someone whose family on her father’s side had a long tradition of political radicalism. Aleksandra inherited or acquired from somewhere a utopian belief in the goodness and wisdom of the ordinary person, perhaps even the uneducated person, who, unencumbered by other people’s teachings would feel his way instinctively to the truth. From this simplicity she and Nicholas would draw advice, and upon this simplicity they would build their nation, the Holy union of Tsar and people. They looked back in some ways to an idealized view of pre-Petrine Russia, in which the state was an instrument of crusading Christianity rather than the other way around.

Aleksandra developed and strengthened the ideas she found in Boehme through reading a variety of mystical and philosophical texts. A favourite was the work of the desert mystic St John of the Ladder – John Climacus - which muses on mankind’s steps to moral perfection. It is easy to see how such a thing would have appealed to a former Protestant.[46] Simultaneously, the ideas of John Climacus work on a national level in accord with Orthodoxy’s desire to see history as a progression towards spiritual perfection; a God-like state. Alexandra could use this book to chart her own attempts to improve herself morally; she could also hold it up as a mirror for the whole Russian nation.

But the best known of Aleksandra’s influences is perhaps Auguste Jundt’s ‘Les amis de Dieu’, an historical and theological book from the 1870s which discusses in some detail the characteristics of a truly holy person as well providing details of some historical Men of God. This is one of only two religious works which gets a mention in Aleksandra’s wartime correspondence with her husband. [47]

From the turn of the century and the days of reading Boehme onwards Nicholas and Aleksandra were ardent in their search for new and popular saints. They promoted the canonisations of Serafim of Sarov, John Maksimovich of Tobolsk and other holy people and hermits who had won themselves a certain reputation amongst ordinary people but who did not always meet the established church’s strict doctrinal criteria for canonisation. This frequently brought them into conflict with the Synod, but they were defiant. Over John Maksimovich, whose canonisation the Synod opposed because it found insufficient evidence of miracles he had performed and because his body had partially decomposed, Nicholas was prepared to simply undercut the Procurator of the Synod – Aleksander Samarin – in ordering laudation to be sung. This stopped short of the full glorification of a saint, but plenty of people took it to be the latter and began celebrating at John’s shrine as if he were already canonised.[48]

Aleksandra was simply furious with Samarin. Her letters rail against ‘narrow minds’, ‘bigots’, ‘real Moscow types…all head and no heart.’ This is her faith in popular religion at work again. She understood that religion could be used to underpin the regime in the eyes of ordinary Russians; and perhaps her motives were pure. To Aleksandra, this was Holy Russia, again; the people know best because Christianity is the natural spiritual state of the people of Russia.

After 1917 there were to be monarchists who felt that the revolution had been caused largely by the weakening of the church’s influence over ordinary Russians. Many historians attribute this weakening to precisely the nature of the church-state relationship that had developed in Russia from the time of Peter the Great and the establishment of the Synod. This overt sublimation of church to monarch undermined it in the eyes of the peasants, who regarded priests as little more than police spies and whose own Christianity was not much more than a veneer on their ancient pagan religion.[49] When people such as this began moving to the cities with industrialisation their religious faith could not survive, particularly since the disorganised urban missions were themselves subject to police infiltration. Even Father Gapon, who led the marchers through the terrible events of the Bloody Sunday massacre that did so much to alter popular perception of the monarchy, was himself a double spy.

In the early years of the twentieth century both conservatives and liberals recognised the problems and wanted Christianity revitalised from the bottom up. Nicholas and Aleksandra were very much a part of this movement: for a variety of reasons the views of a genuinely prayerful peasant would always mean more than the views of the Synod.

Holy fools, Holy Rus

The infamous Grigorii Rasputin was the chief beneficiary of Aleksandra’s and Nicholas’s trust in the holiness and wisdom of simple men. The religious and philosophical basis of this trust is often over-looked though because of the obvious connection between Rasputin’s ascendancy and the illness of their youngest child and only son.

Every school child knows that the peasant preacher Rasputin was the only person able to halt the boy’s bleeding episodes, often when the doctors despaired of his life, and was believed to have become the ruler of Russia as a result, bringing down ministers without rhyme or reason by whispering in the ear of the Empress and her husband, unhinged through fear for their son. This is grossly exaggerated of course: Rasputin had no sway whatsoever over the disastrous policy that lay behind all of Nicholas and Aleksandra’s ministerial decisions, and his influence over individual appointments was smaller than most believed. Although his ability to help the heir to the throne may have secured his position it wasn’t why he was introduced to the couple in the first place. Before Aleksei was even born, Nicholas and Aleksandra had been seeking their spiritual guides. Whether their policies and decisions in ruling Russia were sensible or justifiable is of course a matter for historical debate; but there was nothing especially neurotic or – in Orthodox terms - even unusual in their seeking spiritual assistance in pursuing those policies. Neither can it be said that Rasputin was the only person to whom they listened when they sought advice in choosing ministers or endorsement of their choice.

Rasputin always cast a shadow many many thousands of times bigger than himself.

He tested Aleksandra and Nicholas’s faith severely on several occasions. Most of this had to do with the reports they were sent concerning debauched behaviour, and on one occasion he was asked to go home to Siberia until the scandal abated. Frequently, in popular and widely-read sources, Aleksandra is depicted as primly or foolishly refusing to believe that the dark side of the Holy Man’s character even existed. [50] Although based on the well-meaning assertions in the memoirs of most of Aleksandra’s friends and apologists, this is rather a simplistic view. She was well aware that his behaviour was often less than ideal, but she found herself – or more precisely she commissioned - a book which explained his bad behaviour in terms devout contemporaries would understand. This book is Iurodovye sviatye russkoi tserkov, a treatise on holy fools in the Russian church. The holy fool is a figure well known in Russian religious and literary tradition, tracing its origins to the ancient Byzantine Church and the aspiration of would-be saints to living martyrdom. Monasticism and extreme asceticism belong to the same tradition, but the Holy fool is a more provocative and aggressive figure, an ostensible follower of the Apostle Paul, seeking to lose himself totally in order to gain true wisdom and self-knowledge. Female holy fools of the ancient church posed as prostitutes and invited men to rape them; both sexes drank and incited jeering and stone-throwing. Such people had often played the part of court jester, speaking bluntly with the powerful without any fear of personal repercussion.

Rasputin was a sort of voluntary fool – itself a common enough figure, since it was pride rather than intelligence which distinguished a would-be fool as a charlatan. He very often behaved in ways that brought others’ contempt upon him. When she lent Iurodovye sviatye to a friend, the Empress pointedly underscored paragraphs which explained that holiness and sexual dissolution often went hand in hand [51]. Her letters also casually mention his drinking: ‘He was very gay and merry, tho’ not tipsy’ she told Nicholas after one war-time meeting.[52]

Thus, even in commissioning books to her own specifications, Aleksandra was not simply rationalising or clutching at straws. Ancient though the tradition was, it appeared frequently in contemporary writing: in Dostoevskii, in Tolstoy, in the revolutionary Maksim Gorkii. Gorkii caricatured the fool’s attitude of mind: ‘Don’t you see, Lord, how I torment and lower myself for the sake of your Glory? Don’t you see, People, how I torture myself for the sake of your salvation?’[53]

Many claimed that Rasputin sexually exploited hysterical Petersburg women by preaching a doctrine of actively sinning in order to be saved. They may have been distorting what was a relatively commonplace acceptance of the role of human failings and active humiliation in bringing people to God. At the very least, it is likely Aleksandra thought so. Rasputin’s own thinking on the subject of his sex life and spirituality was undoubtedly more complex.

Aleksandra was familiar with the principles of Christian Science; she read the works of Mary Baker Eddy [54] and believed in the importance of prayer and faith in effecting healing. And yet her own prayers brought no benefit to her child when he was sick. The ascendancy of Rasputin thus throws a further interesting light on Aleksandra’s profound doubts and uncertainty: her own faith was insufficient; she needed the Man of God to pray for her son. Her reading of Mary Baker Eddy appears to suggest that she was well aware of the psychological nature of the Holy Man’s power. ‘“The power of faith shall save the sick” says the Scripture. What is this healing prayer? A mere request that God will heal the sick has no more power to gain more of the Divine presence than is always at hand. The beneficial effect of such prayer for the sick is on the human mind, making it act more powerfully upon the body through a blind faith in God.’ Thus wrote Mrs Eddy. ‘Prayer to a corporeal God affects the sick like a drug, which has no efficacy of its own but borrows its power from human faith and belief.’[55] All the more must reading things like this have emphasised to Aleksandra the inadequacy of her own faith, which on its own could do so little for her child.

Anxiety over Aleksei affected her own health; she developed a heart condition and breathing problems which sound to the contemporary ear like the symptons of prolonged hyper-ventilation. ‘The months of physical and moral strain during our Boy's illness brought on a collapse - for seven years I suffer from the heart and live the life of an invalid most of the time,’ she wrote to Boyd-Carpenter in 1913.

Aleksandra’s faith in Rasputin and related personal interest in peasant spirituality did not impress those who thought they understood that basis for some of the religious customs found in the countryside was paganism rather than Orthodoxy. Some years before she was even born, there was a celebrated controversy in the form of an open letter from Vissarion Belinskii to Nikolai Gogol. This defined the two contrasting views of peasant spirituality that came to exist among intellectuals in the last years of the Tsarist regime. ‘According to you, the Russian people is the most religious in the world. This is a lie! The basis of religiousness is pietism, reverence, fear of God, whereas the Russian man utters of the name of God while scratching himself somewhere. He says of the icon : if it isn’t good for praying, it’s good for covering the pots. Take a closer look and you will see that it is by nature a profoundly atheistic people. It still retains a great deal of superstition but not a trace of religiousness.’[56]

Ironically, the majority of educated society seems to have concurred with view of the cynical critic Belinskii rather than with Gogol’s and the church’s conservative one. It looked down on popular faith and on the Empress’s interest in it.‘She was interested in outward forms of religious worship,’ wrote Paul Benckendorf, the Grand Marshall of the imperial Court with some incredulity, ‘and went so far as to take an interest in local superstitions.’[57]

Certainly Aleksandra’s wartime letters contain some evidence of behaviour that appears to be rather superstitious. She asked her husband to use a comb Rasputin had given him before talking to ministers[58]; this has been read as a sign that she thought the comb had magical powers. That may be a little harsh. Having read Boehme, Aleksandra should have well understood the psychological aspects of faith, and the importance of objects with religious associations. Her faith in the comb was possibly no more than an understanding of its importance as a reminder of what she believed their Man of God stood for and would help Nicholas do.

In the Orthodox Church, icons above all have power in this regard. ‘Man is not pure spirit; he needs tangible representations which evoke for him realities inaccessible to his senses. Thus the Greek Church allows images, while stating very precisely their value as symbols.’[59] Aleksandra accepted this use whole-heartedly. During the Great War she was ever keen for Russia’s holiest icons to be shown to the troops as an inspiration and a reminder of the nature of the war they were fighting for the survival of Holy Russia.

Both she and Nicholas apparently had some faith in prophecy and the importance of dreams, but it is curiously difficult to determine on what level. In December 1916 she took her daughters to visit the ancient Holy Woman Maria Mikhailovna in Novgorod, and reported back to her husband, ‘[She] said the war would soon be over “tell him that we are satisfied”. To me she said, “and you, the beautiful one, don’t fear the heavy cross (several times) “for your coming to visit us, two churches will be built in Russia”….said not to worry about the children, will marry, and could not hear the rest.’[60] Aleksandra sounds oddly casual about the substance of what Maria Mikhailovna was saying, and adds, ‘such love and warmth everywhere, feeling of God and your people, unity & purity of feelings,’ so it may possibly be that she interested herself in these prophets and latter-day saints as an expression of the popular religiosity of the nation rather than a literal source for divining the future.

If she took an interest in superstitions it was not so much that she accepted them wholesale and was naively unaware of their pagan origins so much as that she regarded them as evidence of some form of universal spirituality.

Their tendency to glorify instinct, the uneducated, the irrational, the ‘little man’, which underpinned Nicholas and Aleksandra’s interest in Rasputin and other peasant holy men places them in my opinion broadly within an intellectual movement that was growing across the whole of Europe at that time. At its worst, it prefigured fascism, and Russia’s proto-fascist groups included the vicious Union of the Russian People, which laid great emphasis upon the ostensible religiousness of its members. Nicholas and Aleksandra were happy to patronize this group, and to enroll their baby son, naively seeing it as a form of popular religious and monarchist re-awakening. Nicholas also shared many of its deepest prejudices; Aleksandra however did not. During the war she was to urge the Emperor to make sure that Russian troops entering Turkey as conquerors behaved respectfully towards Mosques and religious shrines: - ‘Please give the order most strongly that our troops should not touch anything that belongs to the Mohammedans - they can use them again for their religion. We are Christians and not barbarians.’[61]

Like many of her age and class, she was however instinctively suspicious of Jews; she was quick to note if a trouble-maker had a Jewish name. On the other hand she did not go so far as to condemn the entire race - in this she and her husband differed strikingly - and she was vocal about the injustice of the legal and settlement restrictions upon Jews to the point where members of the Imperial Family believed her to be personally behind Nicholas’s attempt too late in his reign to repeal them.[62]

Beyond this, Aleksandra respected those who on religious grounds opted out of the mores of civil society in Russia. During the war, she took steps to avoid the conscription of Methodists, reminding Nicholas that it was, ‘against their religious convictions’, and urging him to ensure that they could serve as nurses and nursing assistants instead.[63]

Sainthood and suffering

The Orthodox Church possibly more than any other emphasises the redemptive power of suffering. Even before she had Aleksei, and long before the First World War, Alexandra was profoundly interested in this idea. The letters of even her courtship make morbidly frequent reference to deaths in the family and to natural disasters. Part of this may of course be superstition: she may have been protecting her happiness by showing fate that she wasn’t complacent about it - but this in turn makes it even more clear that the early deaths of her mother and her siblings – not to mention her family’s interest in medicine and the sick - had had an enormous psychological effect on her. Suffering preyed on her mind. Aleksandra seems to have sought to find a meaning for it that was answered by the Orthodox Church’s emphasis upon mankind’s redemption through misery. ‘The school of life is indeed a difficult one, but when one tries to live by helping others along the steep and thorny path ones love for Christ grows yet stronger, always suffering and being almost an invalid, one has so much time for thinking and reading and realises always more and more that this life is but the preparation to yonder real life where all will be made clear to us.’ [64]

She and Nicholas had genuine Holy Fools brought to their homes long before Rasputin appeared on the scene. War, revolution and her son’s illness only intensified her interest, and in 1915 she explicitly mentioned the purifying potential of the war: ‘After suffering and strife, may peace and consolation find their place in the world & all hatred cease and our beloved country develop into beauty in every sense of the word. It is a new birth and cleansing of minds and souls.’[65] ‘This war can mean so colossaly much in the moral regeneration of our Church and our country.’[66]

‘France,’ she wrote to Boyd-Carpenter, ‘where systematically the government was trying to crush out the influence of Church and Religion, has been obliged to get priests for the army. Well, certainly, prayer and work alone can help one through such times of sorrow…’ [67]

After the revolution she continued to be hopeful, both on Russia’s behalf and on her husband’s (the latter now elevated to He and at times referred to as ‘my suffering Saint’). ‘They write so much filth about Him…It gets worse and worse, I throw the papers down…How greatly he suffers inside, seeing all the ruin….I remember the suffering of the Saviour; He died for us sinners and perhaps he will still be mollified….for those who sincerely believe in God, this will be (I can’t find the right word here) as a trial for perfecting their souls.’[68]

She viewed the behaviour of the revolutionaries and those who followed them as anti-Russian and thus - because of the Holy Russia myth - irreligious in destroying discipline and passively bringing about a German victory: ‘One shouldn’t fear being stronger than the bad destructive forces that only try to hasten Russia’s death. They are not patriots and there’s nothing holy in them…the psychology of the masses is a terrible thing.’[69]

‘Oh, people, people! Petty dishrags. Without character, without love for their Motherland, for God…..Just as parents punish their children so he acts with Russia. She sins and has sinned before Him and is not deserving of His love. But he is all-powerful – can do everything He will hear, finally, the prayers of the suffering, will forgive and save….We’ll have to suffer, and the more we have to suffer in this world, the better it will be in the next.’[70]

The Orthodox Church offers numerous examples of people – often princes and rulers - who almost invited martyrdom. Besides the celebrated early Passion-bearers Boris and Gleb, who were murdered by their half-brother, and whose murder was later on the basis of scant or non-existent evidence painted in church texts as a unresisting death, there was also amongst others Prince Iaropolk Isiaslavich, who apparently prayed,

‘Oh Lord my God, receive my prayer and grant me a death from another’s hand, so that I may wash away all my sins with my blood.’[71] Aleksandra’s letter suggests that she wanted to think along the same lines, that she felt she should welcome some form of martyrdom – although when she wrote these words there was no real suggestion that the family might be killed, and in the last weeks and months of its life they were pathetically eager to escape and stay alive. Once again there’s a dichotomy in Aleksandra between what the human woman felt and what the Christian felt she ought to feel.

More than ever though, she became the mystic, reading the Bible daily, studying Church Slavonic, and advocating prayer and contemplation as the steadying and consoling factor in an uncertain world. ‘Life is vanity, eternity is everything. We ready ourselves in our thoughts for admission to the Kingdom of Heaven…everything can be taken away from a person, but no-one can take away the soul.’[72]

Yet there is an unattractive side to some of Aleksandra’s religious pronouncements after the revolution. An element of the ‘sin’ for which she claimed Russia was being punished by God was its ‘ingratitude’ towards her husband in overthrowing him – not just because in her opinion he was a good man who had tried to do his best in a impossible situation, but also because he was the Lord’s Anointed and no-one had the right to touch him. One early chronicler of the Russian monarchy wrote, ‘As the Apostle Paul says, every soul obeys the ruler, for the rulers are established by God…those who oppose the ruler oppose the law of God.’[73] That Aleksandra accepted this idea is clear from her shock in March 1917 that Duma members dared confront and entrap her husband, their Sovereign, and coerce him into abdicating. To ardent monarchists, a blow against a good man is a sin for those implicated, but a blow against God’s Anointed is a stain upon the soul of the entire nation, for which the entire nation must suffer and atone.

‘Don’t you see the miracle of the wrath of God on Russia for their innocent blood?’ thundered one priest a few decades later of the murder of the imperial family.[74]

For Aleksandra it was simpler to characterise the revolution as a ‘sin’ on the part of the nation - or as God's punishment for a sin committed by the nation - than to examine the reasons why it had happened and to confront the possibility that the autocratic policies she and her husband had insisted upon might have played their part.

And yet her comments on sin and ingratitude need in fairness to be kept in the context of her own personal beliefs and value system. She didn’t set her husband above the law inviolable no matter he did; she was genuinely concerned for him to act in total accordance with Christian principles, according to her conception of the Byzantine system, and her fury at ‘ingratitude’ has probably to be seen in this light. In prison, she regarded his submissive character with something approaching adulation, but this did not extend to any illusions about her own, and she wrote much that was conventionally pious about her hopes and fears and love for Russia, ‘ingratitude’, faults and all. ‘…What do people live on now? They take away everything – houses, pensions, money.’ [75]

‘I am still the mother of this country and I suffer its pains as my own child’s pains…At times I am not as patient as I ought to be. I get angry when people are dishonest, or when they unnecessarily hurt and offend those I love’.[76]

In 1981 the last Tsar and Empress and their five children were canonised by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad as martyrs, a status which in doctrinal terms many claim they do not strictly merit. After much discussion, the Church inside Russia followed suit in 2000, but insisted upon the lower and more correct status of Passion Bearers – that is to say, people who underwent suffering and death with great faith and submissiveness, but who did not strictly die for their Christian beliefs. Historically, most passion bearers have been princes, who are thus supposed to intercede in heaven on behalf of the nation just as they interceded in the political sphere in life.

Both canonisations have been the subject of great controversy, since they appear to ignore the political crimes committed by the imperial regime and even by Nicholas personally in his role as Emperor. It has even been argued that the canonization finds favour in Far Right circles specifically because of those crimes: that approval for it is linked to approval for the pogroms of Nicholas’s reign. The ROCA’s canonization in particular seems to be a monarchist gesture, designed to emphasise the sanctity of the imperial regime. The murder of Nicholas II was not merely an immoral act in human terms, the Church literature states, it was a crime against Holy Russia and the Orthodox religion. This is why Nicholas and his family are martyrs to their church for all that their murder was a political one and its spiritual implications were the last thing on the mind of its perpetrators. ‘He was killed precisely because he was a crowned ruler, the upholder of the splendid concept of the Orthodox state.’[77] This concept of the murder as one whose meaning transcends its own immediate reason is indeed linked, furthermore, to the preposterous notion that the murder of the imperial family was perpetrated by Jews, and unfortunately the Orthodox Church Abroad has allowed this blood libel to be repeatedly published in its own literature. [78]

The canonization, whether it be as Passion-Bearers or as martyrs for the imperial regime, tallies nicely with the way the family saw itself in its last days (Nicholas’s diary does not hesitate to blame Jews for the revolution). I doubt though whether Aleksandra would have agreed that she personally deserved it.

Acknowledgements: Greg King drew the Wilton reference to my attention and commissioned the first version of this article. Professor Joe Fuhrmann gave me permission to quote from his work-in-progress, Rasputin, a life for the Tsar. Both my friends are also owed my more general, grateful thanks.

[1] Fallowell, p.143

[2] See Nichols, Robert L. The canonisation of Serafim of Sarov, in Religious and secular

forces in late Tsarist Russia

[3] Alix of Hesse to Tsesarevich Nicholas, 8 November 1893, in A Lifelong

passion

[4] Nichols, Robert L. The canonisation of Serafim of Sarov, in Religious and secular

forces in late Tsarist Russia, p.218

[5] Nicholas’s diary, January 28th 1891, in Wortman, p.327

[6] Aleksandra Feodorovna to William Boyd Carpenter, January 1895, in British Library

add. Manuscript 46721 ff.231-234

[7] Numerous examples cited in Major

[8] James, at www.psywww.com/psyrelig/james/toc

[9] cited, Major, p.136

[10] ibid., p. 155

[11] ibid., p. 149-150

[12] Irène, Princess Henry of Prussia to William Boyd Carpenter, 7th January 1903, in

British Library add. manuscript 46721 ff. 222-4

[13] Various letters in British Library add. Manuscript 46721

[14] Aleksandra Feodorovna to William Boyd Carpenter, February 1913, in British

Library add. manuscript 46721 ff. 240-3

[15] ibid.

[16] Victoria, Marchioness of Milford Haven, to Nona Kerr, 10 November 1918, cited in

Hough, p. 327

[17] Queen Victoria to Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia, 15 June 1883, cited in

Lambton, p. 184

[18] Alix of Hesse to Tsesarevich Nicholas, July 29th 1894, in A lifelong passion

[19] Aleksandra’s notebooks, 1897-1901, cited in Wortman, p.334

[20] Miller, p. 7-14

[21] The complete wartime correspondence, fn., p. 384

[22] Princess Henry of Prussia to William Boyd Carpenter, 1904, in British Library add.

Manuscript 46721 ff.223-6

[23] King, p.107

[24] Cherniavsky, p. 36

[25] Massie, p. 52

[26] Cherniavsky, p. 42

[27] Liebman, Zacariah, The Life of the Tsar-martyr Nicholas II, in The Orthodox Word,

vol. 26, no. 4, p.193

[28] Numerous examples in N to AF and AF to N, 1914-1917

[29] Nicholas II to Marie Feodorovna, 20th October 1912, in A lifelong passion

[30] Aleksandra Feodorovna to William Boyd Carpenter, February 1913, in British

Library add. manuscript 46721 ff. 240-3

[31] AF to Boyd-Carpenter, 11th January 1903, in British Library add.

Manuscript 47621 ff.236-8

[32] See for example Aleksandra Feodorovna to her daughter Grand Duchess Mariia

Nikolaievna, 6 December 1910, in A lifelong passion

[33] Anastasiia Nikolaievna to Nicholas, 28 October 1915, in A lifelong passion

[34] Sidney Gibbes to Robert Wilton, 1919, referring to Tatiana Nikolaevna; in Wilton,

p. 254.

[35] N to AF, April 8th 1916

[36] AF to Boyd-Carpenter, 11th January 1903, in British Library add.

Manuscript 47621 ff.236-8

[37] Leeds University Manuscript 7376 ff.1134 (notebook of Baroness Sophie

Buxhoeveden, 1917)

[38] Jacob Boehme: essential readings p.15-60

[59] ibid., p.57

[40] ibid, p.59

[41] Nicholas to his mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, 20th October 1902, in Bing

[42] AF to N, 22nd August 1915

[43] Church statement at www.roca.org/oa/14/14c

[44] AF to N 5th December 1916

[45] Jacob Boehme : essential readings p.77

[46] Nichols, Robert L. The canonisation of Serafim of Sarov, in Religious and secular

forces in late Tsarist Russia, p.219

[47] AF to N, December 4th, 1916. The other book, a Persian text called “Teachings of

God” was mentioned on September 22nd in the same year.

[48] Fuhrmann, p.135-6

[49] Pipes, p.241-5

[50] See for example, Massie, p 361

[51] Fuhrmann, Rasputin, a life, p.53, and manuscript, Rasputin, a life for the Tsar, which contributes the previously obscure fact that Aleksandra actually commissioned this book.

[52] AF to N, 5th November 1916

[53] Gorkii, p. 158

[54] Anna Vyrubova in Dorr, at www.alexanderpalace.org/palace/annainterview

[55] Eddy, at www.spirituality.com

[56] Cited in Pipes, p. 160

[57] Benckendorff, at www.alexanderpalace.org/lastdays

[58] AF to N, 15th September 1915

[59] Pascal, p.18

[60] AF to N, December 12th 1916

[61] AF to N, 5th April 1915

[62] Grand Duke Aleksandr Mikhailovich (Nicholas II’s cousin and brother-in-law) to his own brother Nikolai Mikhailovich, 14 February 1917, in A lifelong passion

[63] AF to N, Sept. 22nd 1916

[64] Aleksandra Feodorovna to William Boyd Carpenter, February 1913, in British

Library add. manuscript 46721 ff. 240-3

[65] AF to N, April 8th 1915

[66] AF to N, April 5th, 1915

[67] AF to Boyd-Carpenter, 2nd February 1915, in British Library Additional Manuscript

47621 ff.240-3

[68] AF to Aleksandr Syroboiarskii, 29 May 1917, in Steinberg and Khrustalev,

p. 150

[69] ibid., p152

[60] AF to Maria Syroboiarskaia, October 17th 1917 in Steinberg and Khrustalev, p. 197

[71] Rancour-Laferriere, p.19

[72] AF to Anna Vyrubova, 9 January 1918, in Steinberg and Khrustalev., p. 219

[73] Cherniavsky, p.12

[74] cited at www.orthodox.net/russiannm/nicholas-ii-tsar-martyr-and-his-family. Unfortunately this page no longer exists, but there are numerous similar examples

[75] AF to Anna Vyrubova, 9 January 1918, in Steinberg and Khrustalev, p. 220

[76] AF to AV, 16 December 1917, ibid., p. 214

[77] 1981 statement by the ROCA, cited in King, p. 390

[78] See for example http://www.fatheralexander.org/booklets/english/nicholas_ii_e.htm#n6 and Orthodox Word, Vol. 26, no. 4, 1990, which both contain references to “ritual” killings. The web version elaborates to include “strange symbols” on the wall of the murder room. For a scholarly examination of the true ethnic and religious composition of the Tsar’s murder squad, see Greg King and Penny Wilson, “The fate of the Romanovs” (New York, 2003)

Bibliography

Almedingen. E. M. The Empress Alexandra, 1872-1918. (London, 1961)

Beckendorff, Paul. Last days at Tsarskoe Selo. (London, 1927)

Bing, Edward J. (ed.) The secret letters of the last Tsar. (London, 1927)

British Library Additional Manuscript 46721

Buxhoeveden, Sophie. The life and tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress of

Russia. (London, 1928)

Cherniavsky, Michael. Tsar and people : studies in Russian myths. (New Haven, 1961)

Dorr, Rheta Childe. Inside the Russian Revolution (New York, 1918)

Eddy, Mary Baker. Science and health (Boston, 1991)

Fallowell, Duncan. One hot summer in St Petersburg. (London, 1994)

Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (ed.) The complete wartime correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra, April 1914-March 1917 (London, 1999)

Fuhrmann, Joseph T. Rasputin: a life. (New York, 1990)

Fuhrmann, Joseph T. Rasputin, a life for the Tsar (work-in-progress)

Gorkii, Maksim. Literaturno-kriticheskie stat’i. (Moscow, 1937)

Gvosdev, Nikolas K. An examination of church-state relations in the Byzantine and

Russian empires with an emphasis on ideology and models of interaction.

(Lampeter, 2001)

Hough, Richard. Louis and Victoria. (London, 1974)

James, William. The varieties of religious experience (New York, 1997)

King, Greg. The last Empress. (London, 1995)

King, Greg and Penny Wilson. The fate of the Romanovs. (New York, 2003)

Kozlov, Vladimir A. and Vladimir M. Khrustalev (eds). The last diary of the Tsaritsa

Alexandra. (New Haven, 1997)

Lambton, Antony. The Mountbattens. (London, 1989)

Leeds University Manuscript 7376 ff.1133-1134

Lunde, Ingunn (ed.). The holy fool in Byzantium and Russia. (Bergen, 1995)

Major, H.D.A. William Boyd Carpenter: his life and letters. (London, 1925)

Massie, Robert K. Nicholas and Alexandra. (London, 1968)

Maylunas, Andrei and Sergei Mironenko (eds). A lifelong passion: Nicholas and

Alexandra, their own story, (London, 1996)

Miller, James Russell. The beautiful life. (London, 1894)

The Orthodox Word, xxvi, no. 4 (1990)

Paléologue, Maurice. Alexandra-Féodorowna, impératrice de Russie. (Paris, 1932)

Pascal, Pierre The religion of the Russian people. (New York, 1976)

Pipes, Richard. Russia under the old regime [2nd ed.] (Harmondsworth, 1995)

Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel The slave soul of Russia: moral masochism and the cult of

suffering. (New York, 1995)

Steinberg, Mark D. and Vladimir M. Khrustalev. The fall of the Romanovs: political

dreams and personal struggles in a time of revolution. (New Haven,

1995)

Timberlake, Charles E (ed.). Religious and secular forces in late Tsarist Russia. (Seattle,

1992)

Waterfield, Robin (ed.). Jacob Boehme : essential readings, (Wellingborough, 1989)

Wilton, Robert. The last days of the Romanovs. (London, 1920)

Wortman, Richard. Scenarios of power: myth and ceremony in Russian monarchy.

(Princeton, 1995-2000)

Web resources:

www.alexanderpalace.org

www.roca.org/oa

www.spirituality.com

www.orthodox.net

www.psywww.com

www.fatheralexander.org

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map