About the Site and Bob Atchison - Boy who Dreamed of a Palace - Bob Atchison

From Reader's Digest

September 1993

September 1993 by Kristin von Krielser

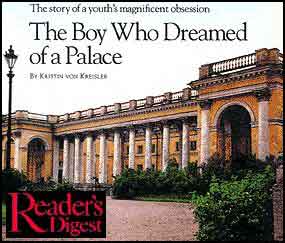

When Bobby Atchison decided to read all the books in his elementary-school library, he came upon a tattered, blue volume with a faded title: I Am Anastasia. It was the story of a woman who claimed to be the daughter of the last czar of Russia-and it was the beginning of a magnificent obsession that would shape the course of the boy's life..

As he turned the book's pages, Bobby's eyes grew wide. Anastasia had lived near St. Petersburg in the Alexander Palace with her parents Nicholas and Alexandra, her brother Alexis, and her three sisters. After Russia was ripped apart by revolution in 1917, the family was taken as prisoners to Siberia, where Bolshevik secret police killed them all - except, perhaps, for Anastasia. No one knew for sure, because the bodies had disappeared.

Bobby, a tall, thin 2nd-grader with a blond cowlick, studied the book. Alone in his room in the town of Mountlake Terrace, Wash., he marveled at the splendor of the Romanovs' life in the Alexander Palace. The boy longed to find out more about such a place, and soon he had read every book on Russia in the town's library.

Bobby, a tall, thin 2nd-grader with a blond cowlick, studied the book. Alone in his room in the town of Mountlake Terrace, Wash., he marveled at the splendor of the Romanovs' life in the Alexander Palace. The boy longed to find out more about such a place, and soon he had read every book on Russia in the town's library.

He pored over photographs of magnificent paintings, gilt furnishings and jewel-encrusted Easter eggs made by the famous jeweler Faberge. He learned that Catherine the Great had built the Alexander Palace in the 18th century. Its style was neo-classical, with the straight lines and perfect proportions of classical Roman temples. Inside, in its more than too rooms, the light from crystal chandeliers glinted off giant urns of malachite and jasper. Portraits of the Romanovs, dressed in satins and brocades, looked down on guests. Silk rugs covered parquet floors of ebony and rosewood.

For a class project, Bobby wrote and illustrated a 100-page report about the palace, including its history, tales of the Romanovs and an imaginary account of visiting them. He also quoted a sentence that his reading had burned into his brain: 'As the Germans retreated from Russia toward the end of World War II, they destroyed all the palaces."

At night, he lay in bed and wondered whether the Alexander Palace had been burned to the ground. In all the books he consulted, he never found an answer. So he whispered a wish night after night: "Please let the palace be all right." Then he vowed: "If it really has been ruined, I'm going to fix it."

Bobby didn't tell anyone about his promise, least of all his parents, who saw the Russians as evil at dinner one night as the family watched the news on television, they saw a furious Soviet premier, Nikita Khruschev pounding his shoe on a desk at the United Nations

Bobby rushed to his room and closed the door. Sprawled on the floor, he started a letter on notebook paper. "Dear Nikita," he printed in large block letters. Even if the powerful leader threatened the world with bombs, Bobby would address him friend to friend. He asked Khrushchev if he'd restore the Alexander Palace and send photos of the building, looking new again. Then the next day, he spent his week's allowance on stamps and dropped his letter in the mailbox.

For months Bobby waited for an answer. None came.

As he grew older, Bobby did all the ordinary things boys do. He earned Boy Scout badges and played little league baseball. He bred guppies in a bowl beside his bed and built camps in the forest.

The more and more he learned about the Romanovs, the hungrier he grew to confide his dream to someone. One day Bobby approached his sixth grade teacher and poured out all his hopes of restoring the palace.

The teacher looked at him. "That's really stupid. You're not going to accomplish your silly dream. get your feet back on the ground."

Bobby blinked and wanted to run away.

The following year, Bobby started dating a girl he was to go out with for six years. her mother was Ukrainian. She fixed him Russian foods and taught him Russian folk songs. As they sat around the kitchen table one afternoon, Bobby said, "I wish we were in Russia."

"You'll get there eventually," she said. "If you believe in yourself and don't give up, there's nothing you can't do."

Bobby Atchison shoot up to six-foot-five. In 1970 he went off to college, where he continued to study Russian culture. After graduation he got a job in San Francisco as a travel agent.

For a year, Atchison skimped and saved and at last, in 1977, at age 24, he flew to Moscow. A few days later he traveled by train to St. Petersburg, then boarded a tour bus to the Alexander Palace.

As flakes of snow pelted the windshield, the bus driver rounded a bend, and through the leafless tress Atchison got his first glimpse of the palace. Heart pounding, he fixed his eyes on the stately yellow building, with white columns and rows of floor-to-ceiling windows.

The palace truly was the magnificent treasure Atchison had always imagined. Now, through the snow, it seemed to shimmer like a vision. It's safe! Atchison thought, relieved and thrilled. Now if I can only get inside...

Leaving the tour group behind, Atchison slogged through the snow toward a fierce looking guard, "I want to get in," he said.

The guard just glowered.

"Pozhaluista... please, can't I go in?" Bob pointed to the building.

"Nyet." The guard's glare warned Atchison not to even step toward the palace. He walked around the fence, craning to see inside. Then he counted the windows, trying to locate Nicholas's study and Alexandra's famous mauve boudoir.

Since 1954, Atchison later learned, the palace had been used as military installation by the Soviet Baltic Fleet; no one without special clearance was allowed inside. Yet whenever he could afford to travel, he returned and tried to sneak in.

Finally, in the summer of 1987, after a dozen visits, Atchison took along a Russian Friend to tell the guard he wanted to speak with the commandant of the palace. This time he was allowed beyond the gate to the palace door, where another guard sent him down a short corridor painted military green, then up a musty flight of stairs. Ahead was a door with a small window.

"How did you get here?" snarled a woman on the other side.

"I want to speak to the commandant," Atchison demanded. "I've been studying this palace all my life. I have to see it."

The woman reached for a telephone and talked excitedly into the receiver, hands waving as she spoke. At last she snapped at Atchison. "There's nothing to see. You have to go! "

On his way out, Atchison noticed 18th-century carvings around two huge doors. So everything isn't gone. The palace had not been completely gutted. Now, even more than as a child, he was determined to see the Alexander Palace restored. But what could one man accomplish alone?

Back home, Atchison had a demanding career managing a staff of 50 people in Apple Computer's corporate travel department. Yet the palace was never long from his thoughts. Even in his dreams he wandered through its rooms. He wasn't sure if he was called to carry out a mission or just obsessed. What was the purpose of his lifelong interest in the Romanovs? Why did they matter to him? Should he push to accomplish his childhood vow? Was it just a fantasy? The words nyet and da chased each other around inside his head.

Atchison traveled to libraries throughout the United States, tracking down every scrap of information available on the Alexander Palace. He enlarged old photographs and studied tiny details of paintings, furniture and window frames. In 1990, he wrote to the directors of every museum in St. Petersburg to win them over to his cause. As with his childhood letter to Khrushchev, he never heard back.

Then he telephoned authors of books on Russia. Many never returned his calls, but some did.

"How should I go about getting the Alexander Palace restored?" he asked. "What do you think the chances are for my success?"

"Nil," they all answered-except for Suzanne Massie, an expert on Russian culture and the author of a book about Pavlovsk, a palace built for Catherine the Great's son and his wife. "You can do it," Massie told him. "But it may take your whole lifetime."

"I still want to try," Atchison responded, unabashed.

Hoping for strength in numbers, he organized the Committee to Restore the Alexander Palace, and through Massie he made contact with the palace's former curator, Anatoly Kuchumov.

When Atchison visited him in his tiny apartment in a retirement home, Kuchumov, a frail man with gnarled hands and intelligent eyes, showed him Alexandra's desk, which he had rescued in 1944 from a trash pile outside the palace. Then Kuchumov brought out albums of photographs Atchison had never seen before and opened boxes of upholstery and drapery swatches that could be copied if the palace was restored.

"The Alexander Palace has been the most precious thing to me," the old man said and began to cry. "I was so afraid it had been lost forever, but you give me hope it will really be preserved."

"I'll do anything I can to save it," Atchison promised.

On a later trip of Atchison's, an admiral of the Baltic Fleet invited him and Massie for a tour of the palace. Atchison's eyes swept over the rooms. Two that had been used by Nicholas and Alexandra had not been completely destroyed: the marble columns in Nicholas's study gleamed in the light, as did the green marble around the fireplace in his reception room. These could be a starting point for the palace's restoration.

But Atchison still had to get Russian officials interested in the project. On a subsequent visit to St. Petersburg, he met Vladimir Gusev, then head of the city commission on culture. Gusev invited Massie and Atchison to attend an upcoming meeting of the commission. One of the topics to be discussed: the future of the Alexander Palace.

Atchison was stunned. Yet he knew he couldn't stay in Russia for the meeting. He'd already been away from his job as long as he dared and had to leave the next morning. Massie would have to speak for him there.

"I've waited my whole life for this," he said to her.

"I know."

For the next few weeks back home, Atchison lived in a fog of distraction. Then one night the phone rang, and he heard Massie's voice. 'Are you sitting down?" she asked.

"Why "

"The commission agreed, in principle, to the restoration of the Alexander Palace," she said. "They welcome your support." Atchison closed his eyes and pressed a hand against his forehead. How could a nobody-kid from Mountlake Terrace have gotten this close to his dream?

In the summer of 1992, just before Atchison left again for St. Petersburg, news came that the skeletons of five women and four men had been "burned from a grave outside

Ekaterinburg, where the Romanovs had been murdered, about 850 miles east of Moscow. Even if the bones were the Romanovs', 11 skeletons should have been in the grave, not nine. Nicholas, Alexandra, their five children and four attendants had died together, according to most reports.

Where were the other two? The czar's son, Alexis, was one of the missing, because no young boy's bones were found in the grave. Many are convinced the missing woman was Anastasia, because for more than 70 years, various women had claimed to be the imperial daughter - including Anna Anderson, whose story had fascinated Atchison as a child. Later, however, he concluded she was an impostor.

Then he read the account of Yakov Yurovsky, commandant of the execution squad, and decided Yurovsky had given a reasonable explanation. After the family had been killed, he claimed, the squad had difficulty disposing of the bodies. The executioners burned the corpses of Alexis and the family's maid, Demidova, whom they mistook for Alexandra. Finally the squad dug a mass grave, dumped in the other nine bodies and drove over them to flatten the earth. The remains of Anastasia, according to this account, should have been in the mass grave.

Some forensic experts, however, suggest otherwise, since they believe none of the remains from the grave are those of a 17-year-old female. Perhaps it was Anastasia's body that was burned along with her brother's. This part of the mystery endures. But scientists in Britain announced in July they had confirmed "virtually beyond a doubt" that the remains of Nicholas, Alexandra and three of their children were among those found in the mass grave.

Last summer, Bishop Basil Rodzianko of the Orthodox Church in America performed a memorial service in Russia for the Romanovs in their family church near the Alexander Palace. Three days later, Bishop Rodzianko, accompanied by Atchison and his committee, led a spontaneous prayer service in the palace's semicircular hall, where the Romanovs had spent their last night before being taken to Siberia. His- tory had at last come full circle: Bishop Rodzianko, whose grandfather led the state assembly that demanded Nicholas's abdication in 1917, was now bringing religion back into the palace. Rodzianko raised his hands and prayed. "Forgive what the Russians have done to you," he said. "Bless this palace. Bless its rebuilding and its restoration."

Please send your comments on this page and the Time Machine to boba@pallasweb.com

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map