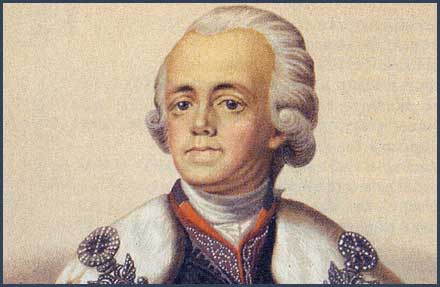

Biographies - Paul I

The Mad Tsar?

Before he was born in 1754, the court of Tsarina Elizabeth Petrovna, daughter of Peter the Great, hummed with gossip about the matrimonial antics of the "Young Court" of Grand Duke Peter, and his wife, Grand Duchess Catherine, or Ekaterina. They had been married over eight years and had yet to produce a child. The Grand Duke, who later was to rule as Tsar Peter III, was physically unable to consummate his marriage to his second cousin, born Princess Sophia of Anhalt-Zerbst. Finally, a courtier suggested a surgical solution to his problem. That courtier, Sergei Saltykov, was rumored to be the lover of Grand Duchess Catherine. In fact, the memoirs of that the Grand Duchess, who was to become Tsarina Catherine II, also known as Catherine the Great, strongly suggest that Paul's father was Sergei Saltykov.

What is known is that Catherine gave birth to her first child under conditions that would be appalling to any woman, regardless of her circumstances. She was placed in a room next to the Tsarina, and her child taken away from her moments after the umbilical cord was cut. The room was drafty, and no attempt was made for hours to clean, warm, feed, comfort, or give medical attention to the young Grand Duchess. Instead, she bled, sweated from the chill of open windows, and thirsted. She lacked the strength to call for help or return to her room. Needless to say, no time was provided mother and son to bond.

But what of the controversy regarding Paul's paternity? Most modern historians believe that there is ample evidence that the House of Romanov died out with Peter the Great's grandson, Peter III. They cite that Peter Feordorovich sired no children on his mistresses and his professed revulsion at Catherine. His early impotence was known at court, and after his surgery, sterility was also suspected.

Short of genetic testing, there is no way to conclusively prove Paul Petrovich's paternity. In spite of the historical consensus of Sergei Saltykov's fatherhood, there is an excellent case for Peter III's paternity of Catherine's son. First, there is a resemblance between other Romanovs and Paul. Catherine the Great, part of the immense Schleswig- Holstein- Gottorp clan, was not genetically related to the Imperial House. Her maternity was never not in doubt. There were also numerous physical and personality similarities between Paul and Peter III. Second, Peter III, who could certainly not be termed a people pleaser, never denied paternity. His hatred of his wife was intense. Had he suspected Paul's being sired elsewhere, he could easily have denounced Catherine as an adulteress. He did not. Third, some historians have theorized that Catherine's suggestion of Saltykov's paternity was an attempt to minimize her guilt in Peter III's subsequent murder by her partisans. She may have had Peter killed, so the theory goes, but she did not want to give the appearance of murdering the father of her son. Last, Catherine the Great was one of the world's most skillful politicians. Her position in Russia at the time was shaky at best, and her only hope for advancement was to perpetuate the Romanov dynasty. Are we to believe this most ambitious of women would jeopardize her hopes and dreams by not fulfilling her dynastic function?

During his childhood, the subject of Paul's paternity was moot. He was alternately smothered with affection from his great aunt, the Tsarina Elizabeth Petrovna, and neglected. His caretakers did not take time to form his character, and his diet was nutritionally deficient, in spite of his family's wealth. Deprived of the opportunity to bond with either parent, and often sickly, he reached adulthood as the ignored, but highly necessary, son of the reigning Tsarina, Catherine the Great.

First Marriage

Catherine faced a dilemma with her son. She needed him alive and well to maintain her fragile relationship with the Romanov family. On the other hand, she and Paul despised and mistrusted each other. Most importantly, he held her responsible for the murder of his father, Tsar Peter III, in 1762. She thought him stupid and ugly. The later was certainty true, but not the former. Something had to be done with Paul, and it was impossible for the Tsarina to share her power with him, or train to him in statescraft. So, she decided he should be married as means of keeping him occupied.

During this time in Europe, Germany, which was not unified until the 19th century under Bismark, was chock-full of small principalities. These states, including Catherine‰s Anhalt-Zerbst, provided a steady supply of royal marriage partners to the rest of Europe. So, it was in Germany that Catherine found her son's brides.

The first to marry Paul was Princess Wilhelmina of Hesse-Darmstadt, who took the Russian name of Natalia Alexievna, upon her marriage on September 29, 1773. At first, all was well, and Paul was happy, while Natalia charmed everyone. It was not to last, as the new Grand Duchess was not at all what she seemed. To start with, she was not loyal, as she soon took Paul's best friend as her lover. Next, she had Catherine's ambition and interest in politics, while lacking her mother-in-law's skill and savvy.

Fortunately for the Imperial Family, but unfortunately for Natalia, she died in childbirth in April 1776. She was unable to birth the child, so her baby died, too. Paul, who had grown to despise his wife as his father had hated his bride, was, at the age of 21, a widower.

A Happy Marriage

The happy marriages that set the Romanovs apart from other ruling houses during this period began with Paul's marriage on September 26, 1776. The second German bride was Princess Sophia Dorothea of Wurttemberg, born October 25, 1759. The princess, who took the Russian name Maria Feodorovna, was serious and purposeful. She and Pavl had 10 children in all over a 22 year period. It was a feat of royal childbirth which few could equal.

Among their children were two future tsars, Alexander I, and Nikolai I, and two future queens, Catherine of Wurttemberg and Anna of the Netherlands. The present Dutch royal family is descended from Anna Pavlovna, who is still greatly loved in her adopted country.

The couple remained devoted for the rest of their lives. Paul did take two mistresses later in his life. His liaison with one of his wife‰s ladies-in-waiting was particularly painful for Marie Feodorovna, as the other woman had been her friend. Paul's relationship during the last three years of his life with a young woman, beginning when she was 19, has the familiar ring of mid-life crisis to it. Nonetheless, by the standards of the day, their marriage was deemed successful and happy.

Also noteworthy is that all of Paul's children remembered him as a tender, nurturing parent. Maria Feodorovna could be cool and remote, seeing them for formal visits only. Her husband was known to go out of his way to include his children in his daily routine. In this, he triumphed over his own emotionally barren upbringing, giving so generously what he himself had never received.

Paul and the Palaces

For a ruler who has been much-maligned, Paul is closely associated with four Russian palaces of historic significance. These are Pavlovsk, Gatchina, our own Alexander Palace, and the Mikhailovski.

In 1777, with the birth of their first child, Alexander, the couple was gifted with Pavlovsk, named, of course, for Paul. At the time, it was a shabby gift, especially when compared with the more opulent treasures Catherine was heaping on her favorite, Potemkin. With his wife's thrift and acumen to back him up, Paul recreated the estate as a masterpiece. Today, thanks to the work of many Russians , and American writer Suzanne Massie and others, Pavlovsk has been restored to its pre-Revolutionary greatness. It is a "must see" for anyone traveling to the St. Petersburg area.

In 1783, the couple had their first daughter, Alexandra. In response, Catherine gifted her son and daughter-in-law with Gatchina, another estate outside of St. Petersburg. Gatchina became their primary home during the later part of Catherine's reign. It was here that Pavl engaged in his paradomania, constantly drilling his soldiers with Prussian precision. As Pavl has often been criticized for this, it is worthwhile to point out that he was a grown man, a husband and father, who was permitted little involvement in the "family business." The blame for this behavior must be shared by the Great Catherine, who was not such a great parent. In later years, Gatchina became the home of Alexander III, and his son, the Imperial Successor, Mikhail Alexandrovich.

Catherine, who suffered so much with Paul being whisked away from her at his birth, did not end the unfortunate pattern. While not as draconian as Elizabeth, she commandeered her grandsons Alexander, Konstantin, and Nikolai away from their parents to raise herself. (Their fourth son, Mikhail, was saved this fate because he was born after his grandmother‰s death.) When Alexander reached manhood, she gifted him with the Alexander Palace. Located in the Imperial Park at Tsarskoe Selo, this kept Alexander close by her at the Catherine Palace. Thus, the Alexander Palace came into being from the affection Catherine felt for Paul's first born, and her desire to control his life.

Paul had the immense Mikailovski fortress built near the turn of the century. This later became an engineering school, attended by Dostoievski, among others. Unfortunately, it was also the site of Paul's murder in 1801.

Tsar of Russia, 1796 - 1801

Catherine the Great died suddenly on November 6, 1796. Although she had expressed an intention of having Alexander succeed her, she never followed through. Thus, at the age of 42, Paul Petrovich became Tsar of all the Russias. He immediately set out to undo as much of his mother's work as possible. In this, he was driven by pettiness and spite, two traits his mother kept under control when it came to her politics.

His first action as tsar, however, was driven by his astute analysis of the shortcomings of the law of succession instituted by his great grandfather. Peter the Great believed that Russian tsars should be able to choose their successors. In practice, this policy was disastrous for the stability of Russia. It caused three palace revolutions during the 18th century, with Peter II, Ivan VI, and Peter III all being deposed. The dynasty lost considerable prestige as a result of the instability of the Romanov dynasty. To correct this, the new tsar issued a manifesto that separated the Imperial Family legally from the rest of the Empire, and established an orderly succession to the throne through the male line. The Pauline law, as it became known, was an important Russian contribution to the Enlightenment period of European history.

While Catherine caused many ordinary Russians to be enslaved through serfdom, Paul was the first Russian tsar to limit the work required of these unfortunate people. At Gatchina, Paul educated their children, lended them money, instituted a system of free medical care, gave them more land for their use, and upgraded agricultural technology. In short, he was a model landlord. When it came to Russia's most humble people, as both tsar and grand duke, he sought to end their suffering and improve their lives. In this, he put into action the Enlightenment ideas parroted, but never followed unless it suited her, by his mother.

To the nobility, Paul was a scourge. He awarded titles randomly, and sought to undo most of the privileges they had gained under Catherine. What Paul lacked was political savvy. Catherine never dispensed a reward or a punishment without carefully thinking it through. Blinded by hatred of his mother, and lacking her as an available target for his rage, the Tsar struck out at her supporters, the aristocracy. Naturally, these powerful people began to plot against this tsar who so loved the peasants, and so mistrusted them.

Paul used much of his wait for the throne studying statescraft. He was owner of 40,000 books, and was as avid a scholar as his mother. In his writings, he was clearer and more precise than his august parent. Unfortunately, he was precluded from practicing what he preached by his mother before he became tsar, and by the nobles who ended his life.

Paul pardoned many of those imprisoned by Catherine, including the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko. He had his father‰s remains reburied in the Fortress of Peter and Paul, and made sure his parents were together in death as they had rarely been in life. In all, he was an inconsistent ruler. For this, his mother must share the blame for his fall by excluding her son from matters of state. If we are to hold Alexander I culpable in the death of his father, we must name Catherine the Great as an accessory.

Deposition and Murder

Plots to remove Paul as tsar brewed for at least a year before Russia's last palace revolution actually happened. Among the chief conspirators were the head of the State Police, Count Pahlen, and Catherine‰s‰ last lover, the politically inastute Count Platon Zubov. The extent of Alexander Petrovich‰s involvement may never be completely revealed, as the Judas-like Pahlen used his office to destroy many documents that could elucidate the matter. What is clear is that a coup conspiracy hatched in 1800 collapsed due to Paul's expulsion of foreign diplomats, including the British Ambassador, who collaborated.

While Pahlen provided the means to dethrone his tsar due to his control of strategic offices, the spark for the successful conspiracy came from the Zubov family. Platon Zubov used his favorite status as Catherine's lover as a career opportunity to advance himself and his family. Naturally, this was lost with Catherine's death. The tsar made a tactical error when he issued a general amnesty in 1800. The parasitic Zubovs used this to return to the capital.

On the night of March 12, 1801, Pahlen, Count Bennigsen, and the Zubov brothers Nikolai and Platon entered the Mikhailovski Castle with the assistance of a co-conspirator, an unfaithful aide-de-camp of Paul's. They found the tsar's bed empty. The conspirators, who were drunk, found their head of state hiding behind a screen in his chamber. In an alcohol induced frenzy, they proceeded to murder the man to whom they had sworn their loyalty. Thus died Pavl Petrovich Romanov, who left the world in circumstances as lacking in love as his entrance.

Please send your comments on this page and the Time Machine to boba@pallasweb.com

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map