Biographies - Nicholas II

The Last Tsar of Russia

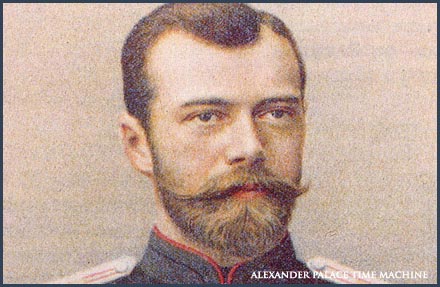

Alexander III was an impressive man, who dominated others by his size and powerful personally. Throughout the 19th century Romanov men had the reputation for being big and imposing. Unfortunately, Nicholas took after his mother. He was about 5'6" tall and his Romanov uncles all seemed to tower over him. He tried to compensate for his height by working out with weights and athletic equipment. No matter what he did to build up his size he still remained slight and wiry in physique. His legs were short, but this was less apparent when he was on horseback. Nicholas looked the most regal when mounted. Most people who meet the Tsar commented on his stunning Danish blue eyes, which some thought were the well to his soul. He always wore his brown hair parted on the left and grew a thick beard filled with golden highlights when he was a young man. It stayed with him throughout his life and became his signature feature, along with the nervous habit he had of brushing his moustache up with the back of his hand. From his father he inherited a pug nose, which he disliked as it reminded him of Paul I, who he considered the ugliest of his ancestors.

Nicholas had an excellent education and was perhaps the best educated European monarch of his time. His parents where astute enough to see the challenges of facing a 20th Century Tsar would be quite different than those of the past and tried to prepare him for his future responsibilities. The very real threat of terrorism loomed over the Imperial Family constantly. Once a bomb blew apart their train car, and only Alexander's powerful shoulders kept the roof from crushing the entire family. A powerful cordon of secret police and military guards protected them, but this meant Nicholas grew up in the isolation of his family. This held him back and he was late in maturing. He never gained a sense of confidence and self reliance. The lack of friends from outside the clan of European royalty deprived Nicholas of the benefit of understanding the way his future subjects lived. In this he was no different than most of his royal peers. But Nicholas was also purposely cut off from liberal thought and ideas by his parents. Since he had almost no contact with Russia's growing intellectual and artistic community he developed narrow ideas of honor, service and tradition which would harm his ability to govern Russia in the future.

While heir to the throne, as Tsarevich, Nicholas achieved the rank of Colonel in the Life Guards. He loved the military and always considered himself an army man. His character and social habits were strongly influenced by his years as a young officer and he made many of his longest lasting friendships among his brother officers. These where his happiest years, when he was almost free of care and worry about the future. His father was still relatively young and Nicholas could expect a few years to fill the role of a dashing, aristocratic officer before he was called to serve his country in an more serious role. The Tsarevich embraced the relative freedom of army life with gusto. He could drink and carry on like the most hedonistic of his fellow officers. Life was full of regimental dinners, concerts, dances and beautiful women. It was during this time he met a young dancer from the Imperial Ballet named Mathilde Kschessinka, who became his first, real girl friend. It wasn't a serious relationship. Both of them knew it couldn't go anywhere and besides, Nicholas had already given his heart to a young, sad eyed and withdrawn German princess named Alix of Hesse. Many thought it was not a good match. Alix wasn't thought to have the right personality traits and outgoing aggressiveness sought in a Russian Empress-to-be. Nicholas could not be persuaded to consider any other bride than Alix, and the couple where formally engaged in 1893. In fall, 1894, Nicholas' father developed a serious nephritis condition which became progressively worse. Alexander's doctors advised a trip to the gentle climate of the Crimea. The famous healer John of Kronstadt was summoned to the Tsar's bedside died in the arms of his wife at Lividia aged 47 from nephritis.

Nicholas felt he was not ready to rule. He knew the weighty task of ruling Russia was greater than his experience and abilities. Yet he believed, even with all his inadequacies and self-doubt, that God had chosen his destiny. The new Emperor took his coronation oath very seriously and saw anointing as Tsar as spiritual experience. After the crown was placed on his head Nicholas would look for support and guidance first within himself and then to God, who had given him this burden. Quickly realising he was surrounded by deceit and the self-interest of bureaucrats and sycophants, Nicholas concluded that on earth he could trust few people. Bullied and misled by his relatives he increasingly turned to his wife for support. Nicholas became cynical and mistrustful of human nature. Loneliness and isolation would be his lot in life.

Above all else, Nicholas loved Russia first and then his family. He thought the fate of the two was inseparable. No one knew the shortcomings of the Romanov Dynasty better than he and yet he felt the monarchy was the only force preventing Russia from coming apart at the seams. Nicholas was intelligent enough to realise the probably of his assassination was quite high. Alexandra's decision to marry him and share his uncertain future was a commitment he always appreciated.

Nicholas was a deeply religious and generally solitary person, who loved the faithful companionship of his dogs to the company of state ministers. Hunting on his estates was a favorite pastime, where he could avoid the tumultuous politics of St. Petersburg and the pestering affairs of his ministers. Rather than living in the Winter Palace at the center of the city, Nicholas chose to live in the countryside nearby. The Alexander Palace became his primary home and Peterhof his seaside retreat. In his palace, the Tsar worked alone at his desk. Refusing to have a secretary, he conducted business on his own, assisted by his aide-d-camp, officials of the Court and his valets. Nicholas was a hard worker and diligent about state business, although his accomplishments where severely limited by his tendency to focus on detail rather than the big picture. He was uncertain of his own opinions on things and felt asking for advice to be a sign of weakness or hesitancy. Therefore he tried to follow his own 'instincts' which were limited by his experience and narrow upbringing.

Nicholas loved music, particularly Wagner. Tristan and Isolde was his and Aleksandra's favorite piece of music. When he could find time, writing to friends or reading were favorite pastimes after spending time with his family. Nicholas was intensely private and abhorred being touched by strangers, though he wasn't standoffish. People fond him extremely affable and kindly in nature.

Though lauded for his admirable personal qualities, as an absolute autocrat Nicholas has been deemed a failure. He found it impossible to reconcile his own strict views of what was right and wrong for Russia with the responsibility of a modern monarch to compromise his own views for the good of the nation.

Not an unintelligent man, but hesitant to draw his own conclusions, Nicholas vacillated on important issues. Lacking political savvy and instinct, he was seldom sure how to handle the affairs of state. This made him come across as weak and contradictory to his ministers. They found it difficult to read his true thoughts and found it hard to follow his leadership. Although it has been strongly argued by others, Nicholas' political decisions were not dominated by his wife, Aleksandra. He made up his own mind and the fact that they agreed on so many points only indicates the closeness of their political instincts concerning Russia.

In the end, in the weeks before the revolution, Nicholas was completely broken by his responsibilities and family problems. His health was bad but he did his best to conceal his exhaustion and physical pain (further signs of his own weakness to Nicholas) from others. The suddenness of his abdication was a further sign of an uncertain and troubled man.

Please send your comments on this page and the Time Machine to boba@pallasweb.com

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map