Bob Atchison's guide to rare and antique roses and where to buy them with special focus on David Austin Roses and Antique Rose Emporium

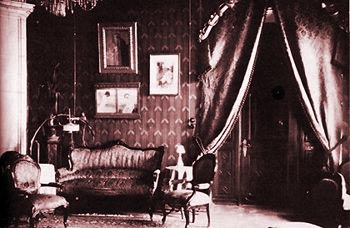

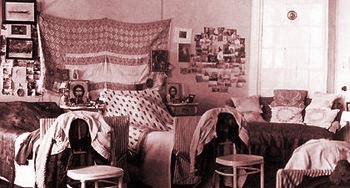

Chapter XXXTobolsk, August 1917 to April 1918The difficulties at Tsarskoe Selo before the departure showed how unwilling were the extremists to let the Imperial Family out of their clutches, and how little authority the Government really enjoyed. The place of exile chosen by the Government was Tobolsk, a town far off in the most deserted part of Siberia. Here they arrived safely on August 19th. At Tobolsk was the shrine of St. John, to which the Empress had sent Mme. Vyrubova on pilgrimage on her behalf in 1916, and she tried to see a good omen in this coincidence. The Government had seen to the outward comfort of the travellers during their long journey. They had a special train, made up of first-class sleeping cars, to which a restaurant-car was attached. There were armed soldiers with them, but the men on duty were at the end of each coach and not actually in the carriage. A member of the Duma, Vershinin, had been deputed to accompany them, as well as the engineer, Makarov, who had made all the arrangements for the journey, and two members of the "Soviet." In order not to excite suspicion, and to avert the possibility of delay, the train was said to be taking a Japanese Red Cross mission across Siberia. There were, however, a few stoppages, and when the train passed through any large station all the blinds were drawn. The train was stopped daily for about half an hour to allow the Emperor and the children to take exercise. The Emperor was asked by the deputies to keep away from the engine in case the driver might recognize him. The Grand Duchesses, with the elastic spirits of youth, when they had got over their first grief at leaving Tsarskoe, began to take an interest in their new surroundings. The Empress lay all day in her carriage, utterly exhausted in both body and mind. She had been terribly disappointed at not going to Livadia. This was really exile, and she felt that Siberia had been chosen to emphasize the point. She got some consolation from the fact that the deputies were civil to the Emperor. The few soldiers in the train were a vast improvement on the horde at Tsarskoe, as Colonel Kobylinsky had carefully chosen the most reasonable men from the Rifle regiments to form their guard. Some of the men talked in a friendly way to the children, and even, at one stopping-place, picked some cornflowers and gave them to the Empress who was leaning out of the window. At Tyumen the whole party was transferred to the steamer Russ, as there was no railway line to Tobolsk. It was said that the company had wanted to put their largest and finest boat at the Emperor's disposal, but the river Tobol was too shallow at that time of year and the smaller Russ had to be used. It was a fairly comfortable boat, and the Imperial Family were delighted with this part of the journey. They had the illusion of freedom, and the scenery reminded them of their trip on the Volga during the Romanov celebrations. The country along the banks was very thinly populated, and they passed very few villages during their thirty-six hours' voyage. One of these villages was Pokrovskoye, the birthplace of Rasputin. The Empress could not help remembering that he had said to her that, willingly or unwillingly, they would pass his house some day. The population kept away from the river banks. They were not hostile to the Imperial Family, but, even if they knew who were the travellers in the Russ, they feared to get into trouble by showing their sympathy with such political prisoners. The first impression of Tobolsk, as seen from, the steamer, was a favorable one. The town was picturesque, built for the most part on the high banks of the river at the spot where the Tobol falls into the mighty Irtysh. The sunset light gilded the domes of the churches, and the bells, ringing for vespers, reminded the travellers of the bell-ringing on official visits in happier times. It looked peaceful and pretty.  Above: The Governor's Mansion in Tobolsk; the Romanovs where imprisoned here. They discovered too soon, however, that this was an outward impression only. Nothing had been prepared for them in the house destined for their use. The want of proper arrangements for their departure from Tsarskoe had already shown that the former Sovereign was of no importance even to those who were not aggressively hostile. Prince Dolgorukov and General Tatistchev, who went to inspect the house with Colonel Kobylinsky, pronounced it uninhabitable in its present state. It had originally been the Governor's residence, but had since been used as a barracks and was indescribably filthy. The Archbishop Hermogen, who had fallen into disfavor with the Court owing to his hostility to Rasputin, had been appointed by the Provisional Government to the see of Tobolsk. He now offered his own residence to the Imperial Family. This house had the advantages of a private chapel and a garden, but the rooms, which were really only a series of large halls, were most uncomfortable, and it had to be declined with many thanks. It was finally decided that the Governor's house should be painted and cleaned, and while this was being done the Imperial Family stayed on board the steamer. This they really enjoyed. They were allowed to take short trips up the river, and disembark for walks, the guard following them at a reasonable distance. They were encouraged to hope that the captivity at Tobolsk might be milder, especially as the gentlemen-in-waiting were allowed to walk freely about the town while they were making the arrangements for the furnishing of the house. All the necessary furniture was bought from private individuals in the town, and the house was ready on August 26th. The Imperial Family moved into it on that day, the Household being lodged in a house opposite, belonging to a merchant named Kornilov. The Emperor and Empress went to see the quarters of their suite on the day of their arrival. This was to be the only time they were allowed to leave their house. There had been vague suggestions before leaving Tsarskoe that the Grand Duchesses might be given more freedom. It had been pointed out several times by the Commandant that they were not under arrest, but had only joined their parents willingly, as had the members of the Household. Kobylinsky had even hoped that the Emperor might be allowed to have some shooting when he was settled at Tobolsk. The actual conditions turned out to be very different. The Imperial prisoners were not permitted to leave the house, except to go to church occasionally on Sundays, or on great holy days, and then they were accompanied by a strong armed escort. The severity towards them increased as time went on.  Above: Alexandra's Sitting Room in Tobolsk. The house, when it was finally ready, was fairly comfortable. Some private possessions, carpets, favorite pictures, etc., had been sent from Tsarskoe by order of Makarov. Their Majesties had a bedroom, the Emperor a dressing-room, the four Grand Duchesses shared a bedroom, and the Tsarevich had his own, with his sailor servant in a room next door. There was a sitting room for the Empress and a study for the Emperor on the first floor, besides a large hall where, later, a portable church was erected. The dining-room was on the ground floor. M. Gilliard and some of the personal servants also lived in the Governor's house, the rest of the servants were with the Household in the house opposite. Countess Hendrikov, Mlle. Schneider, and the gentlemen-in-waiting had all their meals with the Imperial Family. They were allowed to cross the street unattended, as the distance was quite short. For some time, indeed, the suite were allowed to take walks by themselves in the town, but this was gradually discontinued. At first they were allowed to go out on certain days only. Then their walks had always to be taken under the escort of an armed soldier, and after the New Year even these restricted outings were very seldom allowed. The Imperial Family got what air they could in the kitchen garden belonging to the Governor's house. This was a very small space with nothing in it but a few cabbages, and to it a part of the street had been added, hastily enclosed by high wooden palings. This enclosure became a quagmire in autumn, as it was unpaved. There was not a single tree or bush in it. Winter begins early in those northern regions, the first snow generally falling in September, but 1917 was an exceptionally mild year and there were no heavy snow falls before the beginning of November. But the climate in Tobolsk is severe, and in January the temperature went down to 50 C. below freezing point; there was, however, no wind, which made it bearable, and the sun shone brightly every day for a couple of hours. Above: Nicholas and Alexei cut wood in Tobolsk. The great drawback of the house was its extreme chilliness. In the Governor's time there had been a special system of heating, used, probably, regardless of cost, but now there was not much fuel, and the whole family suffered terribly. The temperature in the rooms was often not more than +7 C. Even the Empress felt half-frozen, and her fingers were so stiff with chilblains that she could not wear her rings, and could scarcely move her knitting-needles. The Grand Duchesses, who always felt the cold, wore all the warm clothing they could find.Tobolsk was a small town of about 30,000 inhabitants and was quite out of the world. It was only during the four summer months that the navigation of the river was possible, and during the rest of the year all communication with Tyumen, 287 versts away, had to be kept up by horses. It would have been impossible for the prisoners to escape. If they had attempted it, the alarm could have been given by telegraph before they were twenty miles away, and there were very few villages on the long stretch of land from Tyumen to Tobolsk. Any such idea, however, was far removed from the thoughts of the Emperor and Empress. They were glad to be away from the political turmoil, and hoped that in that desolate place they might be forgotten and allowed to stay in Russia, their own wish to the last. On New Year's Eve, 1917, the Empress wrote to me: " Thank God, we are still in Russia and all together." The people of the town were not hostile. It was too far away for propaganda to have penetrated, and patriarchal customs still prevailed. The Emperor was still the Emperor in Tobolsk, and many people bared their heads when they passed the Governor's house. When the Imperial party were taken to church, the crowd was kept at a distance, but there were many who crossed themselves as the Emperor went by. Many of the merchants, too, sent gifts of food, some openly, some anonymously. These were very welcome. In that severe climate the only vegetables were cabbages and carrots. Potatoes had to be brought from Tyumen. Fish was plentiful, of course, and there was an abundance of game. There was no garrison at Tobolsk, and the guard, under Colonel Kobylinsky, consisting of 350 men from the Tsarskoe Selo Rifles, was the only authority. At first they seemed inclined to a more gentle regime, and Colonel Kobylinsky and his officers kept control over their men. But under the influence of ceaseless propaganda, his authority weakened. The Provisional Government had appointed a civilian Kommissar, in the person of Vassili Semenovich Pankratov, a former political prisoner, who had spent the best part of his life in Siberia. He was not a bad man, though his first term of detention in his youth had been on a charge of manslaughter. He had been imbued with the most extreme doctrines of socialism, and was really a fanatic with ideals. He and his assistant, a coarse, half educated man called Nicholsky, insisted on reading socialistic lectures to the soldiers. At first these did not affect them, but gradually, out of boredom-they had not much to do-they began to discuss their "rights." The Commander's orders began to be disregarded, and the little Soviet assumed greater importance. Pankratov himself was always afraid of the soldiers. He would have given more liberty to the Imperial children, whom, personally, he rather liked, but he would not take upon himself the responsibility of authorizing it. Much harm was unwittingly done at this time by the sudden arrival at Tobolsk of a girl friend of the Grand Duchesses, Marguerite (Rita) Serguevna Khitrovo, one of the honorary maids-of-honour. She had had no post at Court, but had nursed in the Empress's hospital, and had conceived a great admiration for the Grand Duchess Olga Nicholaevna. During her journey she behaved most foolishly, and wrote imprudently worded postcards to her family, which excited the suspicion that she was con-ling on a political errand. When she reached Tobolsk in September, she walked straight into the Kornilov house to see Countess Hendrikov. No one was allowed to enter the house without a special permit. She was, of course, seen by the soldiers the alarm was given, and Mlle. Khitrovo was immediately arrested and taken to Moscow. She had brought some perfectly innocent letters for the Imperial Family, which she intended to give to Kobylinsky to pass on to them, but she had broken the rules, and her visit to Countess Hendrikov resulted in a cross-examination and a day's arrest in her room for the Countess, and many anxious moments for the Commander. It was ultimately proved in Moscow that Mlle. Khitrovo had no political importance at all, and that her journey was undertaken solely from a desire to see her beloved Grand Duchess. She was released, but the prisoners at Tobolsk suffered from her escapade. Though the Imperial Family had not seen her, the soldiers were incensed by this breaking of rules, and increased their vigilance and severity. They feared that "plotting" was going on, and it was in consequence of Mlle. Khitrovo's visit that the suite were allowed out only under armed guard. When, in November, the Empress's dresser, Madeleine Zanotti, and two maids arrived from Tsarskoe Selo, they were not admitted, though they had the necessary authority from Kerensky. A similar fate befell me also, when I arrived. Though I was allowed to stay at the Kornilov house with the other members of the Household for some weeks I had ultimately to lodge in the town, though I could see the members of the suite every day; and while I lived in the Kornilov house, I was never once allowed to go out for a walk.  Above: The Bedroom of the Grand Duchesses. The morning after my arrival at the Kornilov house at Tobolsk the Empress wrote to me at 8 A.M.:Xmas Eve, 1917No one from outside was allowed to see the Imperial Family, except occasionally dentists, or an oculist for the Empress, all brought in by the Kommissar Pankratov and Kobylinsky. Doctor Derevenko's son, Kolia, was allowed to come and play with the Tsarevich. Even at Christmas the rule was not relaxed, and Doctor Botkin's son and daughter, who lived with their father in the Kornilov house, were not allowed into the Governor's house, on the plea that they were not the Imperial children's usual playfellows, as they had never been invited to the Palace, either at Tsarskoe Selo or at Livadia. In November the news of the Bolshevik revolution of November 7th reached Tobolsk. It was so far away that it produced no change. The officials of the Provisional Government, including the Governor, remained at their posts, the banks were open, and the law courts continued to work. Moscow was ignored, and while the money lasted Tobolsk ruled itself. The guard had become used to their prisoners and were, on the whole, polite to them. There were, however, continual small conflicts and occasional rows. There was trouble, originated by Nicholsky, over some St. Raphael wine which was kept in reserve for the children. This was triumphantly poured out into the river. But, on the whole, things jogged on till Christmas, when the soldiers allowed the Imperial Family to spend as many hours as they liked in their enclosure, presented arms to the Emperor, and greeted him with the usual "Good morning, Colonel," in answer to his salute. A more serious unpleasantness, and one that the Empress felt greatly, occurred at Christmas, when the priest made an unfortunate slip of the tongue in praying for the Imperial Family, and gave them their former titles. It was never discovered if it was the priest or the deacon who had done this, but the soldiers raised a hue and cry, and the priest was threatened with imprisonment. With the greatest difficulty, the Archbishop managed to have this sentence commuted, but the priest was sent away and the Imperial Family were bereft of the comfort of a "real" church. After that time their church-going was a rare occurrence, as the soldiers raised objections every time, and the Archbishop finally helped them out of their difficulties by allowing a temporary chapel to be erected in the house. When the soldiers realised that the November revolution seemed to have installed the Bolsheviks permanently in Moscow, they began to see that the authorities at Tobolsk had no Government to back them up. The soldiers enforced their opinions more and more and the officers had to conciliate them, knowing that they had now nothing to rely on but their personal prestige. So long as the men's pay was in Colonel Kobylinsky's hands, however, and he could pay it regularly, things went on more or less as before. They had obliged the officers to take off their badges of rank and decorations, and the Emperor was asked to do the same so as not to tempt the men to force him to do so. But the men were clearly getting the upper hand. The Empress saw the change in the soldiers, but she hoped it was only a passing phase. She wrote to me at Christmas: A blessed Xmas to you, Isa dearest! And a loving wish and kiss. Above all, I wish God to give you good health, peace of mind, "doushevny mir " [peace of soul], which is the greatest gift. We can ask for patience, which we all need in this world of suffering (and utter madness), consolation, strength and happiness. A "Joyful Xmas " might sound like mockery, but it means joy over the New-born King, who. died to save us all, and does not that renew one's trust and faith in God's infinite mercy? He is so far above all, is All in all: He will show mercy, when the right time comes, and we must patiently and resignedly await His good will. We are helpless to mend matters-can only trust, trust and pray and never lose faith or one's love to Him. Prayed for you, and shall again at mass - too hard you cannot go. I so hoped by a side door to another church. The Emperor and all the children send many a message and good wish. They share my regret. God bless you. Won't you look out of your window and tell Nastinka [Countess Hendrikov] when? At one, let's say, and then we can peep at the comer window, and perhaps catch a glimpse of you. just off to church! God bless and protect you.The Empress's deep religious faith had come to her aid and helped her to beat her trials with fortitude and be hopeful to the end. At Tobolsk she gained that unearthly calm which sometimes comes to those who feel the Great Shadow before them, without, perhaps, entirely realising, its nearness. She had fought so hard against her human weaknesses that she had attained to the real Christian humility and trained her proud spirit not to rebel. During those long months of introspection she learned to look, in all sincerity, at trials and hardships as a gift of God, a fit preparation for the future blessed life. She had always seen the Life Eternal as her ultimate goal, and now that her links with earthly things were slackening, she saw the gates of Heaven very near. Both the Emperor and Empress had realised the danger to their own lives from the beginning of the Revolution, but though the Empress hoped for no mercy from the extremists in Moscow, who were most of them not Russians at all, she still trusted that no real Russian would ever lay hands on his Tsar. She was convinced that her children were in no actual danger. She foresaw a sad future for her daughters, spending their youth in such tragic circumstances, but she did not fear for their lives. All through her own troubles, Alexandra Feodorovna thought of others, not only those actually with her, but those far away. Notwithstanding their ever-increasing financial difficulties, she managed to send parcels of food to humble friends at Tsarskoe Selo, where by this time people were nearly starving. Things were indescribably worse in Russia than they ever had been in Imperial times. All the Empress's letters at this time are full of concern for her friends, and show, more clearly than any words of mine, the thoughts that filled her mind. She wrote to Mme. Vyrubova from Tobolsk in March: My heart is troubled, but my soul remains tranquil, as I feel God always near. Yet, what are they deciding on at Moscow? God help us! ... Peace, and yet the Germans continue to advance further and further.Again: When will it all finish? How I love my country, with all its faults 1 It grows dearer and dearer to me, and I thank God daily, that He has allowed us to remain here and did not send us further away. Believe in the people, darling. The nation is strong and young and as soft as wax. just now, it is in bad hands, and darkness, anarchy reigns. But the King of Glory will come, and will save, strengthen and give wisdom to the people who are now deceived.She liked to believe that the Lenten season and coming Spring might work a change in men as well as in nature: Soon spring is coming to rejoice our hearts [she wrote to the same correspondent on March 15th, 19 18 ]. The way of the cross first, then joy and gladness. It will soon be a year since we parted, but what is time? Life here is nothing - Eternity is everything, and what we are doing, is preparing our souls for the Kingdom of Heaven. Thus, nothing, after all, is terrible, and if they do take everything from us, they cannot take our souls. . . . Have patience, and these days of suffering will end. We shall forget all anguish and thank God. God help those who only see the bad and don't try and understand that all this will pass. .In another letter she says: All is in God's will. The deeper you look, the more you understand that this is so. All sorrows are sent us to free us from our sins or as a test of our faith, an example to others. It requires good food to make plants grow properly and the gardener, walking through His garden, wants to be pleased with His flowers. If they do not grow properly, He takes His pruning knife, and cuts, waiting for the sunshine to coax them into growth again. I should like to paint a picture of this beautiful garden and all that grows in it. I remember English gardens and at Livadia you saw an illustrated book I had, so you will understand. just now eleven men passed on horseback - good faces, mere boys. I have not seen the like for a long time. They are the guard of the new Kommissar. Sometimes we see men with the most awful faces. I would not include them in my garden picture. The only place for them would be outside, where the merciful sunshine could reach them and make them clean from all dirt and evil, with which they are covered.Count Benckendorff had said of the Empress after she had heard the news of the Emperor's abdication: "Elle est grande, grande . . . mais j'avais toujours dit, que c'etait un de ces caracteres qui s' elevent au sublime dans le malheur." Those who were with her during her captivity at Tsarskoe Selo and at Tobolsk can vouch for the truth of those words. The Empress spent her long days in preparing the lessons she continued to give her two children, German to the Grand Duchess Tatiana and the Catechism to the Tsarevich, since the priest could not be counted on for lessons, after the trouble about the names in church. She got up late at times, and had her meals with Alexei Nicholaevich in her own room. She read a great deal, worked, copied out music and practise the singing of the responses for the church services, at which both she and her daughters joined in the chants. She very seldom went out, but sometimes, when it was fine and warmer, sat in the sun on her balcony, well wrapped up. When the others were out she would often spend hours at the piano. She had no music, but played from memory, passing from one favorite piece to the other, as the spirit moved her. In the evenings, when all the Household were present, if the Emperor did not read aloud the Empress would play bezique with him. She had, all her life, had a feeling that cards were a little wrong, but sacrificed her own conscience in this case in order to amuse him and help him to pass the time. His days were terrible in their monotony. He read, and gave history lessons to his son, but for a man of active brain and body, such a life was unutterably wearisome. Happily, they could all go out into their courtyard whenever they wished, so that he could get exercise in the open, either in shovelling away the snow or in sawing wood. He also helped the children to build a small ice-hill for the Tsarevich, which was a great pleasure to all the young people. It was a sign of the change of mood in the soldiers after the New Year that they destroyed this ice-hill on the ground that from it the children could see the people passing in the street. For a long time before Christmas the Empress and her daughters worked at Christmas presents for all the Household and servants. They made most of these gifts themselves. This gave the presents greater value and was, at the same time, a saving of expense. There was a Christmas tree, and the commander and the little Tsarevich's tutors took part in the family fete. The Botkin children and I were not allowed to join the party, and to us the Empress sent little trees adorned by herself. Even my old governess whom she had never met was not forgotten. The Empress had drawn her a little picture of holly to remind her of Christmas in England, which she sent with a note begging her to "allow a countrywoman's daughter to send her the small gift she had made for her, with her warm wishes." The young people seemed cheerful enough, but the two elder realised how serious things were becoming. The Grand Duchess Olga told me that they put on brave faces for their parents' sake. The younger children did not realise their danger, and the Grand Duchess Marie said once to Mr. Gibbes, in the early days of their stay, that she would be quite content to remain for ever in Tobolsk! In the course of the winter they even acted a few small plays in French and English, which made a welcome diversion. The two tutors coached them, and the Grand Duchess Anastasia, in particular, showed a decided talent for comedy. Even the Empress laughed during these performances, and took great interest in them, for her children's sake, writing the programmes, and helping the actors to dress up. The sole audience were the suite and the servants living in the house, and, of course, the commander was present. After January new difficulties arose for the Imperial Family. Matters of which they had never even thought now forced themselves on their notice. Up till this time the Government had paid for the upkeep of the establishment. When the first Provisional Government was replaced by the Bolsheviks, funds ceased to come from Petrograd, and Kobylinsky had difficulty in providing the pay of his men. In order to supply the wants of the Household, Prince Dolgorukov and General Tatistchev signed bills in their own names, but the merchants were becoming anxious ; and the shops were reluctant to give further credit. There was still some money left of that provided by Count Benckendorff for the journey, but in order to make this last as long as possible, it was necessary to practise the most rigid economy. When Prince Dolgorukov explained this to the Empress, she talked the matter over with the gentlemen-in-waiting and it was settled that she, Prince Dolgorukov and M. Gilliard, a practical Swiss, would undertake the housekeeping together and work out the lines on which it could be managed with the minimum of cost. Some of the servants had to be discharged, the Empress giving them enough money to take them back to Petrograd, should they wish to go there. Those that remained offered to work without pay. This the Empress would not agree to, though she was much touched by their offer, and all the salaries were proportionately cut down. The members of the Household joined in paying the kitchen bills. The one o'clock dinner was the chief meal, and consisted of soup, a dish of meat or fish, and some stewed fruit. Supper was generally of macaroni or rice or pancakes followed by vegetables. Often "gifts from Heaven," as the Empress called the anonymous presents of fish and game, came to supplement this somewhat meagre fare. When these were not forthcoming, there was only just enough to go round - no second helping for anyone. There were no luxuries, of course, except when as a very rare treat a rich merchant sent some caviar or some specially fine fish. Sugar was very scarce, three lumps a day being doled out to each person. Coffee was unknown to everyone, except to the Empress, to whom it played the part of a medicine. Butter was dispensed with, except when it came as a gift. The Empress's fine underlinen gave way under the merciless washing of the local laundry. There was no money to buy new things, and in any case neatly all the shops, except those that sold necessaries, were closed, the few articles that were smuggled through from Japan being sold at fancy prices. As it happened, a few friends heard of this particular difficulty, and sent the commander some underlinen and warm clothes for the Empress and her daughters. She was quite overcome with gratitude, and afraid that the givers must have deprived themselves on her account. Thus the long, dark, winter days dragged on monotonously, all striving to keep up intellectual interests in order not to be affected by the small, petty incidents of semi-prison life. What was particularly painful during those tedious months was the lack of reliable news as to what was happening in the world. Letters came irregularly. The Bolshevik regime had stopped the working of the post, and there were so many Tchekas to be passed by letters before they reached Tobolsk that numbers were lost on the way. When letters did come, no one dared write openly, even to the Household. The newspapers that reached Tobolsk contained nothing but official telegrams, distorted and coloured by the Bolshevik authorities. I remember, for instance, having seen an account, giving full details, of a revolution in Denmark in 1918, and was very much surprised when 1 arrived there next year to hear that there had been nothing of the kind. Still these papers, such as they were, gave us all the news we had, and through them we were able to gain a slight impression of the effects of the Revolution. The Emperor and Empress were distressed beyond words at the state into which the country was drifting. This was the thing that poisoned their lives. Russia's fate was still their main thought. All the Empress's notes to me were filled with this idea. Her letters to Mme. Vyrubova show the same feeling, though more carefully worded, as these letters had to pass the censorship of the post. She wrote: "I cannot think calmly about it-such hideous pain in heart and soul. Yet I am sure God will not leave it like this. He will send wisdom and save Russia, I am sure." The Brest-Litovsk peace was a great blow-their real agony, for the Emperor's great sacrifice had been in vain. In February orders came from the regimental headquarters at Tsarskoe Selo that some of the older men of the guard were to be relieved, as their time was up, while others would be sent to take their places. It seemed that the men had become rather uneasy at being still under the orders of the old Provisional Government, and had secretly sent two of their number to Moscow to see what was going on. These men had been well received, and on their return had told their comrades that the new rulers seemed firmly established and had to be reckoned with in the future. In the meantime Moscow had remembered Tobolsk. A Soviet was elected in the town by Moscow's orders, the Governor retired, and in the second half of February Pankratov and Nicholsky left hurriedly, as the new soldiers from Tsarskoe Selo had threatened to imprison them. Soon after a man called Doutzmann was appointed Commandant in succession to Pankratov, and took up his quarters in the Kornilov house. These new soldiers were of the same type as those under whom we had suffered at Tsarskoe. When the old guard left, some of the men came secretly to take leave of the Imperial Family. They had ended by having a real liking for the children, and were altogether less hostile than they had been at first. At the end of March more soldiers arrived at Tobolsk. Up till this time the town had been spared. At Tyumen bands of sailors had struck terror into the inhabitants, looting and imprisoning under the pretext of "requisitions," but they had not undertaken the long horse journey to Tobolsk. Now Tobolsk had unwelcome visitors in its turn. No one knew if they were sent under orders from Moscow or not, but it was surmised that the new arrivals came of their own accord. On Match 26th a band of soldiers arrived from Omsk, the chief town in Eastern Siberia, and its administrative centre. They took up their quarters in the girls' schools, under the command of a certain Dementiev. Except that they saw that the Bolshevik regime was carried out everywhere, their arrival did not cause many changes in the town, and they did not interfere with the Imperial Family's guard. They were followed by another detachment from the neighboring mining centre, Ekaterinburg. The soldiers that formed these detachments were mostly Letts, some former sailors and some Ekaterinburg workmen. The people of Tobolsk were terrified by them. Well-to-do merchants were arrested and imprisoned every day, in order that they might be bailed out by their families for large sums. Requisitions began, and posters were hung up in the streets, saying that all gold and silver and valuables must be given up to the authorities under penalty of death. The men started domiciliary visits with, or often without, search-warrants from the local Soviet which was now in command. The Omsk and the Ekaterinburg bands did not seem to get on well together, and in April the Ekaterinburg men departed to exact requisitions from Beresov, a town in the extreme north. They were replaced in a few days by another detachment from Ekaterinburg with a Jew, Zaslavsky, at their head. Though every party of newcomers may have hoped, secretly, to get possession of the Emperor and his family, they did not try to do this forcibly ; for the regular guard announced that if anyone tried to take their prisoners from them, they would kill the whole Imperial Family themselves before they gave them up. The soldiers of the guard were getting perceptibly nervous, however, at all these new arrivals. They feared that they would be replaced if they did not show extreme severity in their treatment of the prisoners, and, in consequence, they forbade the suite to go out, were very severe with the servants, and even insisted on paying a domiciliary visit to the Governor's house, to see that there were no arms hidden away there. Colonel Kobylinsky managed to pacify his men by providing new occupations, and charged them with guarding the wine stores in the town. This was a paid duty that had been carried out by Austrian prisoners, but as the latter were leaving in accordance with the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, they had to be replaced. In April orders came from Moscow for the arrest of the "citizens Dolgorukov, Tatistchev, and Hendrikov", and the two gentlemen and the two ladies (Mlle. Schneider being included by Kobylinsky) were taken over to the Governor's house (April 13th). This was now greatly overcrowded, and the newcomers had to live two and three in a room, as the ladies were accompanied by their maids.  Above: One of the last pictures of Alexei; from Tobolsk. The Empress was not blind to the meaning of these changes. She wrote to Mme. Vyrubova on April 3rd, 1918 : "Though we know that the storm is coming neater out souls are at peace. Whatever happens will be through God's will. Thank God, at least, the little one is better." She had anxiety for the Tsarevich added to her other burdens, for he had been dangerously ill. He had caught whooping-cough from his playfellow, Kolia Derevenko, and had burst a blood-vessel in coughing. The internal haemorrhage was nearly as bad as during his attack at Spala. Dr. Derevenko was in despair, for he lacked nearly every drug he needed in the badly stocked little town. Alexei Nicholaevich had been very well up till this time, as had his sisters. They had German measles in January, but on the whole had not suffered from the climate. The Empress sat day and night with her boy, only allowing the Grand Duchess Tatiana to relieve her for a few hours. The pains were intolerable, the fever was high, and the boy's life hung in the balance. Happily, Dr. Derevenko tried a new remedy, which proved successful, and the bleeding stopped. The fever was still extremely high, however, and the patient very weak when the blow fell. The leaders in Moscow had at last turned their attention to the prisoners at Tobolsk. No one in Tobolsk knew why they chose that particular time nor what they meant to do. The arrival of the special envoy, Yakovlev, was a surprise to Kobylinsky, and, apparently, to everyone else. Yakovlev came on April 22nd, provided with full powers. His arrival was shrouded in mystery. He was guarded by a band of mounted soldiers and had two assistants, a sailor, called Khokhriakov, and a former officer, Rodionov. The first named had apparently been a stoker on the Alexander II. Yakovlev himself, though he, too, wore the dress of a blue-jacket, was of higher social standing. It appeared that he had been a political refugee, and was a man of some culture. His arrival completely threw Doutzmann into the shade. He assembled the guard and loaded them with praises, telling them that the Government intended to pay them highly as a reward for their loyal service. He seemed to Colonel Kobylinsky to be a man accustomed to handle the masses. The soldiers and local Soviet were impressed by his credentials, which were signed by Sverdlov himself. According to them, it was for him to give orders now. He had to be obeyed, as he could have anyone executed without trial if he wished. He was, evidently, an important person. Nothing was said at first about the motive of his mission, but it was soon evident to Colonel Kobylinsky that he intended taking the Imperial Family away. He seems to have realised that it would be impossible to move Alexei Nicholaevich in the state he was then in, for, after having been to the Governor's house and seen the whole family, he returned a second time to see Alexei Nicholaevich and then had long telegraphic communications with Moscow. Yakovlev had told the guard that they and Colonel Kobylinsky would now be relieved of their duties. The Colonel remained nominally at his post till May 14th, but all the orders were given by Yakovlev and Rodionov. Kobylinsky gathered the impression that Yakovlev was not personally hostile to the Emperor, and he was, in fact, rather optimistic after he had got over the first shock of the new regime. General Tatistchev was not so hopeful, and told me that he considered this the most dangerous crisis the Imperial Family had ever gone through. On April 25th Yakovlev told the Emperor that he was going to take him away, though he did not say why or where. When the Emperor refused to leave, Yakovlev said that if he persisted in his refusal, he should have to use force, as his instructions were to remove him. There was general consternation. Everyone thought that it was to Moscow that the Emperor would be taken, and who knew what might happen there? This was the most terrible time of all for the Empress. She was torn between her feelings as a wife and as a mother. She felt that she could not allow the Emperor to go alone. On the other hand, her boy lay dangerously ill, and the idea of leaving him in that state drove her nearly out of her senses. It was the only time that she completely lost her self-command, pacing up and down the room for hours in her perplexity. The Emperor's departure was imminent and some decision had to be taken. At last the Grand Duchess Tatiana forced her mother to come to a decision. "You cannot go on tormenting yourself like this," she said. The Empress summoned all her courage, and went to the Emperor to tell him that she had made up her mind to go with him. The Tsarevich could be looked after by his sisters, and she felt she must be with the Emperor. The girls settled among themselves that the Grand Duchess Marie, who was the strongest, physically, of the sisters, should go with their parents. Olga Nicholaevna was to take charge of the house, Tatiana Nicholaevna was to look after her brother, Anastasia Nicholaevna was too young to be taken into account. Prince Dolgorukov had asked the Emperor which of the gentlemen should go with him, and the Emperor had chosen him. Dr. Botkin also appeared, carrying his well-known small black bag, and when he was asked why he had brought it, said that as he was, naturally, going with his patient (meaning the Empress), he might need it. The Imperial Family spent the rest of that day alone. The sick boy had to be prepared for his parents' leaving, and the Empress spent most of the time with him, trying to treat her departure in a casual way so as not to frighten him, and telling him that he and his sisters would soon follow her. In the evening the Household joined the Imperial Family at tea. The Grand Duchesses all sat as close to their mother as they could, looking the picture of despair. About three a.m. their Majesties took leave of their Household and the servants. About four some springless carts were drawn up before the main entrance.  Above: The waiting carriages. The one destined for the Empress had a hood, and into this she was lifted; Dr. Botkin said that it was impossible that she should travel in such discomfort -the carts had no seats - so some straw was brought from a pigsty to put at the bottom of the cart, over which some rugs and pillows were arranged. The Empress motioned to the Emperor to follow her, but Yakovlev said that he had to travel with him, and the Grand Duchess Marie got in beside her mother. Yakovlev stood at attention when the Emperor came out, and the sentry presented arms. Yakovlev was, on the whole, respectful in his manner to His Majesty, and was even considerate, insisting that the Emperor should take an extra coat. In the third tarantas, as the springless Siberian carts are called, Prince Dolgorukov and Dr. Botkin took their seats. In the fourth were Matveyev, an officer of the Tobolsk guard, and one of the Empress's maids, Anna Stepanovna Demidova. The Emperor's valet, Chemodurov, and a servant, Sednev, completed the party. A mounted escort, consisting of some of Yakovlev's men and a few of the Rifles, who had insisted on accompanying the Emperor, surrounded the carts and the whole convoy drove off at four a.m. at full speed, clattering over the streets in the dim, morning light. The three Grand Duchesses stood looking after them, and it was a long time before their lonely figures disappeared behind the open door. The journey was terrible, and it can be imagined what the Empress suffered when she was rattled at full speed over the awful Siberian roads. These roads are shocking at the best of times, and just then were at their worst, for the snow and ice melted during the daytime, and froze again into hard lumps at night. The Empress sent me a line from Tyumen, saying that all her "soul had been shaken out." Several times wheels came off and broke, and the harness gave way. They travelled all day, spending some hours at night fit in a peasant's house! where they slept on the camp-beds they had brought with them, the Emperor and Empress with their daughter in one room, the gentlemen in another. The ladies were nearly frozen. Someone who saw them at one of their stops said that when the Grand Duchess got out to arrange her mother's cushions, her hands were so cold that she had to rub her numbed fingers for a long time before she could use them at all. She and the Empress wore thin coats of Persian lamb suitable for motor-car driving in Petrograd. They had to get over several rivers, where the ice was so unsafe that they were obliged to cross by planks on foot. At one place the Emperor had to wade knee-deep in ice-cold water, carrying the Empress in his arms. The state in which they reached Tyumen can be imagined, yet the Empress begged Yakovlev to send an encouraging telegram to her children, saying that they had "arrived all well." At Tyumen a train was awaiting them. It seems likely that it was Yakovlev's original intention to take them to Moscow. There are two ways of reaching that city from Tyumen. The one westward, through Ekaterinburg, the other by going first eastward to Omsk, branching off from there via Cheliabinsk. Yakovlev chose the latter to avoid Ekaterinburg, where there was an ultra-Red Soviet. They reached the station before Omsk safely, but the authorities at Omsk were evidently afraid that the prisoners might escape further east and would not allow them to be taken beyond their town. Yakovlev had many discussions with the Omsk Soviet, and spoke direct to Moscow. As a result of the instructions he got, the train was turned back towards Ekaterinburg, which had evidently been warned of their arrival. When the train stopped outside the town, a large band of soldiers surrounded it. Yakovlev went to the local Soviet, and there, apparently, resigned his powers, and the Emperor and Empress were handed over to the Ural (Ekaterinburg) authorities. The Emperor, Empress and their daughter, with Dr. Botkin, the maid and the two men-servants were taken in motor cars to the house of a local engineer named Ipatiev where they were imprisoned. Prince Dolgorukov was taken to the prison in the town (April 30th). The Empress was utterly weary in body and spirit. She was hardly able to stand when she left the car. She had no news of Alexei Nicholaevich. The letters she had written daily to her children had no answer, and she was desperately anxious. Happily a telegram soon came from the Grand Duchess Olga Nicholaevna describing an improvement in the boy's health, but she never got most of the letters the children wrote her. Still she seems at first to have had hopes that the stay at Ekaterinburg would not be a long one, and her chief trouble seems to have been her children's absence and the idea of their journey. |

|

Alexandra Feodorovna was the last Romanov Empress of Imperial Russia. This online book - The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feororvna was written by Countess Sophie Buxhoeveden, Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress, who served the Empress for many years and followed the Imperial family into exile. |

- Early Surroundings

- Childhood

- A Young Princess

- Engagement

- Marriage

- Her New Home

- Coronation

- Journeys

- Charities and Life

- Queen Victoria

- Foreign Trips

- Birth of Alexis

- Gathering Clouds

- On the Standart

- Rasputin

- Her Family

- Empress at Home

- Last Years of Peace

- Wartime 1914

- War Work

- Without the Emperor

- Visits to Headquarters

- Before the Storm

- Warning Voices

- Rasputin's Murder

- Revolution 1917

- Abdication of the Emperor

- Prisoners

- Five Weary Months

- Tobolsk

- Ekaterinburg 1918