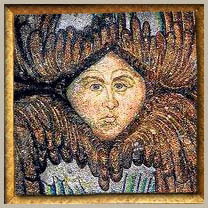

This page from the Hagia Sophia website is about the famous 15th century image of angel on the left side of the apse whose face was recently uncovered

Chapter XXITsarskoe Selo Without the EmperorThe retreat of the summer of 1915 was marked by many glorious deeds. The officers and men were wonderful in their heroic endurance and resistance to forces superior in numbers, in arms, and in equipment. The losses were terrible. The continual reverses which gave the Whole country reasons for the gravest anxiety pointed to some serious defects in the Organization. The Emperor heard much criticism of the Staff. From the very outset of the war the Emperor had been displeased to note that orders from Headquarters were often in opposition to orders from the Home Office in the parts of the country near the seat of war, and grave inconvenience resulted. There also the Staff was blamed. The troops, on the other hand, were beginning to be discouraged by the disasters. The Grand Duke Nicholas could not be persuaded to make a clean sweep of those of whom the most bitter criticisms were made. There seemed to be only one way in which to make a complete change and at the same time inspire the army with new energy. The Emperor decided to take the supreme command himself. His first idea was to retain the Grand Duke Nicholas at Headquarters so as to avoid any appearance of slight to him. The course presented many difficulties, and the Grand Duke was appointed Commander-in-Chief on the Caucasian front. The Empress Alexandra Feodorovna had an idea that the Grand Duke Nicholas was unlucky. Intrigues of every kind were rife in Kiev, where the Grand Duchess Nicholas resided, intrigues of which the Grand Duke himself was probably ignorant, but which ill-disposed people attributed indirectly to him. Her Majesty knew that the Emperor's whole soul was at the front, and was convinced that his presence would put new spirit into the troops, and though to her personally the separation was a real tragedy, she felt it her duty to support him; it would mean victory. On September 4th the Emperor left for Headquarters. In an Ordre du Jour, dated September 5th, he reaffirmed his former resolution not to conclude peace while a single enemy was left on Russian soil. These words were now more impressive', for nearly all Poland was in the hands of the enemy. The Empress wrote to her sister: Nicky will take over the command, General Alexeiev will have the chief work to do, as head of Nicky's Staff. He will guide the whole thing here as the other place [Mohileff] is still further off and then he will constantly go and see the troops and know what's going on at last.... It's a heavy cross Nicky takes upon himself, but with God's help it will bring better luck.The Emperor's idea in taking the command in hand was to make short stays only at Mohileff, leaving the actual command to General Alexeiev, his Chief of the Staff. This plan, unfortunately, was not adhered to. The crowds of people of every class and condition, flying from their homes., some with a few of their goods and chattels, some quite penniless, even reached Petrograd. They were put by the municipality into every available building. The Empress immediately went to see all the places where they were housed, even the emergency barracks on the island of Golodai, where hundreds of people, men, women, and children, were all herded together, glad to get even this miserable shelter. The Empress visited every corner, questioning the people about their needs, and devising measures to improve their condition. After the Emperor had taken over the command, news from the front became better, and General Alexeiev succeeded in keeping the Germans in check until winter put a stop to serious military operations. This improvement seemed to the Empress a good omen, and her belief in the wisdom of her husband's decision was strengthened when she heard all the officers in her hospitals praising it. With the Emperor at Mohileff, twenty-six hours distant from the capital, life at the Imperial Palace became, if possible, even quieter. The whole place seemed dead. There was no movement in the great courtyard. We ladies-in-waiting went to the Empress through a series of empty halls. The Empress gave audience daily, but only to those people whom it was imperative to see, including a few on charitable business. Her latest bout of activity had exhausted her much more quickly than at the beginning of the war, and a month after the Emperor's departure, Her Majesty, though still going when possible to the Tsarskoe Selo hospitals, spent most of the day and all her evenings on her sofa, in a state of utter exhaustion. But no matter what was in her heart, she always had a smile for her children; they always found their mother interested in their doings. Her face would light up whenever the Emperor or one of her children came into the room. After dinner the Empress and her daughters sat together in the mauve boudoir, the children round her couch. One daughter would play the piano, another would read. Mme. Vyrubova was nearly always with the party. When the Emperor was at Tsarskoe and had a moment's free time, he would read aloud, generally an English novel, which rested his brain. The young Grand Duchesses never seemed to feel the austerity of their lives, or expect the amusements that should have been theirs at their age. The only changes they had were an occasional concert got up at the hospital for the patients, or a small party at Mme. Vyrubova's, to which the Empress sometimes accompanied them. Mme. Vyrubova had a charming little house near the Palace. She knew how to entertain simply and informally, and invited to those small parties a few intimate friends. Her sister, Mme. "Alya" Pistohlkors (married to the son of the Princess Paley by her first marriage), was generally there; Countess Emma Freedericsz, Mme. Dehn (Lily), Countess Rehbinder, née Moewesz (looking very like the Empress in appearance, though shorter), as well as some young girls, Irina Tolstoy, Daly (Nathalie) Tolstoy, Marguerite Khitrovo, and some officers of the Imperial yacht, when they were on leave from the front. The realities of war were known to the Empress. She heard accounts of life at the front every day at the hospitals, and from the reports of officers on leave she realised that the spirit that prevailed at the front was very different from that in the rear. The officers from the army were full of hope, energy and patriotic feeling. Those who had been some time in the Petrograd hospitals were dispirited and full of alarming tales. The hope that the Emperor would be able to make short stays only at Headquarters could not be fulfilled. He did not return to Tsarskoe till October, and then only for a short time. When he was there the Palace sprang to life. Ministers came and went daily, carriages drove to and fro. He was satisfied that all was going well and was full of hope for the future. When the Emperor left, he took the Tsarevich with him. He wanted the troops to know his heir. He also wanted his son to see at close quarters what war meant, so that he should be able to understand, in years to come, what the struggle had been and what it had cost Russia. This was a terrible wrench for the Empress. She had never been parted from her boy for more than a few hours, except for one week on one of her inspection journeys. Every moment she was away from him she was filled with anxiety that something would happen, for the sword of Damocles was always hanging over his head. She made up her mind that she must make this, the greatest of all sacrifices. She would part with her peace of mind and let her treasure go ; she was always anxious when her vigilant eye could not guard him. It was for her son's future and also for the Emperor's sake; he was often lonely at Mohileff, and the boy would cheer him up-but the look of anxiety never left her face from that day. Her war work had little by little shown the Empress many defects in Government machinery. She heard that her ambulance trains were often held up at some point owing to insufficiency of railway lines. There was lack of supplies caused by slowness and disorder, as well as by mismanagement. On December 10th, 1915, she speaks in a letter of a "shortage of flour and meat in many places though they exist in quantities, but fugitives and troop; take all the trains." She did not realise how much all this influenced the political situation of the country. There was no one to give her accurate information on the subject. She never spoke about politics to either her gentlemen or ladies : the subject was taboo at Court. Rumours of what was being talked about in the capital sometimes reached her, but through the chance words of some of the wounded in her hospitals or through nurses and doctors. Another occasional source of information was Mme. Vyrubova, who went about a great deal in spite of her lameness. Her father, Alexander Sergueievich Tanayev, was not only a prominent government official, but also a composer of some repute ; artists, members of society and Ministers of State all met at his house. Mme. Vyrubova also frequently went to the house of the Princess Paley, the wife of the Grand Duke Paul, who had a kind of salon at the time. Unfortunately, Mme. Vyrubova, although she collected many stories from various sources, was not a very reliable or discriminating informant, and found it almost impossible to separate idle gossip and rumour from sound information. Many who knew that she was the Empress's friend flattered her, and she was apt to be deceived. Anyone who expressed the slightest criticism of the Government was put down as "bad." Mme. Vyrubova always identified the Government with the person of the Emperor. Any censure of the Government was considered by her as disloyalty to the Crown. The Empress tried to sift out her friend's reports, but they always left an impression, for Her Majesty knew the absolute and wholehearted devotion of her friend "Ania" to the Imperial Family. She knew, too, that the things "Ania" repeated were probably the talk of the town, although, unfortunately, she did not know of how small a section of it. The death of the Empress's devoted lady-in-waiting, Princess Sonia Orbeliani, in December 1915, Was, as well as being a great personal grief, a loss to her in other ways. Though she had been an invalid for years, Princess Orbeliani had the undaunted spirit of the Georgians. She did not give in, though she knew that her days were numbered, and kept to the last an intense interest in life. When she could no longer serve her beloved Empress actively, Princess Orbeliani did all she could to help her socially, putting her in touch with people who would interest her, and talking to her frankly, never fearing to give her an honest and even unfavorable opinion. She went about a great deal in her wheeled chair to houses where the voices of different parties were heard. She was a niece of the former Liberal Prime Minister, Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky. The Empress was devoted to Sonia, and knew her honesty and affection. Her Majesty did not easily change her opinion when it was once formed, but in discussing a subject with a person she trusted she could be persuaded in time to see the other point of view, and even to act on it later. Nothing that the Empress did, or did not do, brought about, or could have averted, the catastrophe of 1917. But had she had wiser advice during the critical years, she would have escaped the unjust accusation of influencing the politics of the country. Sonia Orbeliani died after a short illness. The Empress never left her during the last day. She had promised her friend to close her eyes when she died, and she kept her promise. Sonia died in her arms, thanking her Empress and friend with her last smile for all she had been to her. The Empress saw to all details of the funeral, fulfilled her dear friend's last wishes, and wrote to all the relations herself. She came to the first memorial service (panihida) in her nurses' dress. "Don't be astonished to see us [the Empress herself and Olga and Tatiana Nicholaevna] dressed as sisters," she wrote me, " but I hate the idea of going into black for her this evening and feel somehow nearer to her like this, like an aunt, more human, less Empress." Late that same evening the Empress joined me in the room where the coffin lay. She sat down beside it, looking into the quiet, dead face, and stroking Sonia's hair, as if she were asleep. "I wanted to be a little more with Sonia," she said. When she left the room, her face was bathed in tears. She felt the loss of the " true heart," as she called Sonia in a letter to her sister, adding "All miss her sorely." Misfortunes never come singly. On the day of Princess Orbeliani's funeral, the Emperor arrived unexpectedly from Headquarters with the little Tsarevich, who was desperately ill. He had broken a blood-vessel in the nose, and all the doctors' efforts could not stop the haemorrhage, which had lasted for forty-eight hours. The poor child had to be supported day and night in a half-sitting posture, and could scarcely speak. The Empress was in an agony. Always calm on the surface, she lived over again in remembrance the hours at Spala in 1912. Again the last remedy-the prayers of the Healer-was called for. The Staretz came, prayed for the child, touched his face, and, almost immediately after, the bleeding ceased. The doctors tried to explain the medical reasons for this, but the mother had seen that all their efforts had failed, and that Rasputin had succeeded. The Tsarevich recovered, and the reputation of the Staretz as a man with heaven-sent powers stood higher than ever. |

|

Alexandra Feodorovna was the last Romanov Empress of Imperial Russia. This online book - The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feororvna was written by Countess Sophie Buxhoeveden, Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress, who served the Empress for many years and followed the Imperial family into exile. |

- Early Surroundings

- Childhood

- A Young Princess

- Engagement

- Marriage

- Her New Home

- Coronation

- Journeys

- Charities and Life

- Queen Victoria

- Foreign Trips

- Birth of Alexis

- Gathering Clouds

- On the Standart

- Rasputin

- Her Family

- Empress at Home

- Last Years of Peace

- Wartime 1914

- War Work

- Without the Emperor

- Visits to Headquarters

- Before the Storm

- Warning Voices

- Rasputin's Murder

- Revolution 1917

- Abdication of the Emperor

- Prisoners

- Five Weary Months

- Tobolsk

- Ekaterinburg 1918

Left: Nicholas II with his troops.

Left: Nicholas II with his troops. Right: Nicholas at Stavka.

Right: Nicholas at Stavka.