Why a web page may look different on different computers. This article that was written by Walt and is on the Pallasart site.

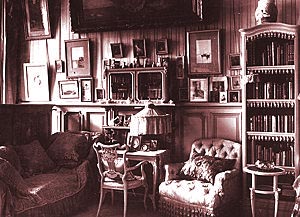

Chapter VMarriage and First Year In Russia, 1894-1895 Above: The Wedding of Nicholas and Alexandra in the Chapel of the Winter Palace The next morning (November 7) the new Emperor, the Dowager-Empress, and Princess Alix went to Holy Communion in the Livadia chapel. It was, perhaps, the most momentous day in Princess Alix's life, for she had that morning been received into the Orthodox Church by Father Yanishev. The body of Alexander III lay in state at Livadia for nearly a week, while the complicated funeral ceremonies were being planned and prepared in Moscow and St. Petersburg. According to an Ukase of the Emperor, Princess Alix had become "the truly believing Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna" and her name, as the Emperor's betrothed, was coupled with his in the litanies of the Church. The new Emperor was overburdened with work and with the weight of overwhelming new responsibilities. He clung to Princess Alix, and would not hear of her returning to Darmstadt, as had been planned, to wait for a wedding in the spring. The question of an immediate marriage was raised, and, feeling that it would have been the wish of the late Emperor, the Dowager-Empress wanted it to take place before Alexander III's funeral. The Emperor's uncles, however, opposed this, considering the event to be of too great importance in the eyes of the nation for such a private ceremony. The Ministers supported this opinion, and it was settled that the marriage should take place at the earliest possible date, at the Winter Palace at St. Petersburg, and that the Princess should not return to Hesse. On November 8th the funeral cortége left Livadia, the Black Sea fleet acting as convoy. Princess Alix went with the young Emperor and the Dowager-Empress in the Imperial train which took Alexander III's body from Sebastopol to Moscow and St. Petersburg. It was a long, sad journey lasting several days. At every large station, and every town, immense crowds, headed by the local authorities, were waiting. The Imperial Family left the train and long, solemn funeral ceremonies were held. The Imperial Family all assembled at St. Petersburg to meet the funeral train, and Princess Alix's first entrance into her future capital was in a weary funeral procession. It was a contrast to the usual state entrance of a Grand Ducal bride. The remembrance of the Grand Duchess Serge's fairy-like procession must have struck Princess Alix, as she sat in her mourning coach, rocking on its cee-springs like a ship in distress, for the long four-hours' drive. The sorrowful atmosphere could not fail to depress her, and seemed to her like a bad omen for the new reign. The body of the late Emperor now lay in state in the cathedral at the fortress. Services were held twice daily. The endless litanies, incomprehensible to her, the woeful chants and prayers of the complicated funeral ceremonial seemed to Princess Alix like a long, sad dream, through which she felt that she must keep up her courage for the sake of her fiancé, and her very genuine grief made her show the warm side of her nature to her new relations. But that whole time was always blurred in her memory. The Princess could, of course, see very little of the young Emperor at St. Petersburg, as State duties claimed him between the church services. She waited impatiently for the fast approaching day of her wedding, when she would be able to be with him constantly and be a real help to him. The severing of her home ties was thus made easier to her than would have been the case under ordinary conditions. She did not return to Darmstadt, but spent the twelve days before her marriage with the Grand Duchess Serge. The wedding took place on November 26th, a week after the funeral. It happened to be the Dowager-Empress's birthday, and so a relaxation of Court mourning for the day was allowed. Many princes, who had come for the funeral, remained for the wedding; among them the bride's brother, the Grand Duke of Hesse, the Prince and Princess of Wales (Edward VII), and Prince and Princess Henry of Prussia. On the wedding morning, the Dowager-Empress, a pathetic figure dressed, like the bride, in white took her future daughter-in-law from the Serge Palace to the Winter Palace, in the great chapel of which the ceremony was to take place. Princess Alix was dressed for her wedding in the Malachite drawing-room of the Winter Palace. Her hair was done in the traditional long side curls, in front of the famous gold mirror of the Empress Anna Ioannovna, before which every Russian Grand Duchess dresses on her wedding day. The chief dressers of the ladies of the Imperial Family assisted, and handed the crown jewels, which lay on red velvet cushions. The Dowager-Empress herself placed the diamond nuptial crown on the bride's head. She wore numerous splendid diamond ornaments and her dress was a heavy Russian Court dress of real silver tissue, with an immensely long train edged with ermine. From her shoulders flowed the Imperial mantle of cloth of gold, lined with the same royal fur. These robes were carried by chamberlains, and so heavy were they that, when the marriage ceremony was over, and the Imperial Family, with their guests, had retired to the Malachite room, the Grand Duke of Hesse saw his sister standing motionless and alone in the middle of the room (the Emperor had left her for a moment), unable to move a step! The train was so heavy that, when it was not carried by the chamberlains, she was almost pinned to the ground by its weight. We see her impression of the ceremony in the following letter to her sister: PALAIS ANICHKOVNo festivities of any kind followed the marriage ceremony. It took place in the morning, and immediately afterwards the young Imperial couple drove to the Anichkov Palace, enthusiastically cheered by the huge crowds which lined their route. They stopped at the Kazan Cathedral on their way, to pray before the greatly venerated ikon of Our Lady. The Empress in later years often went to this cathedral between the services, with one of her ladies in attendance. She used to kneel in the shadow of a pillar, unrecognized by the few people in the church, who did not guess who was the lady who, so unobtrusively, bought a taper and put it before the ikons. The Emperor's marriage had been arranged so suddenly that no preparations had been made for the young couple in any of the Palaces. Alexander III had lived almost entirely at Gatchina, at an hour's distance from St. Petersburg, and had used the small Anichkov Palace in the capital in winter. The Winter Palace at St. Petersburg was the official residence of the Emperors of Russia. It was a series of gigantic halls, flanked at both sides with vast suites of apartments. Since the death of Alexander II in 1881 no one had lived in it, and it was used only for balls and receptions. The Emperor Nicholas II meant to live in the rooms of his great-grandfather, Nicholas I, but these had to be thoroughly renovated. In the meantime the young couple accepted the hospitality of the Dowager-empress, and it was settled that two rooms (making six rooms in all) should be added to the Emperor's bachelor quarters at the Anichkov Palace, where the Dowager-empress would continue to live. Happily love gilds everything, for anything less comfortable could scarcely be imagined. The rooms were small, and not designed for a married couple, much less for an Imperial one. Their Majesties shared one sitting-room, and consequently could not give audience simultaneously. They had no proper dining-room, which would have prevented their having any guests, had not deep mourning made this anyhow impossible. From the very first day the young Emperor and Empress took their meals with the Dowager-empress. Indeed, so dutiful was the Emperor to his mother and so fearful of hurting her by introducing any change, that at first the Emperor and Empress even went to her apartments for breakfast, though this was later given up. In these small rooms Alexandra Feodorovna sat all day, moving into her bedroom when the Emperor gave audience in the sitting-room. But she was entirely happy. Her husband was near her and, whenever his work allowed, he came to her room for a cigarette and a few words, and found her always waiting for him. Sovereigns have no holidays. Nicholas II, whose wedding took place on November 26th, resumed his work on the 29th, receiving his ministers in the morning, and working with them exactly as Alexander III had done. There was no honeymoon proper; Sovereigns are not allowed such things, and Princes are never alone. It was very, very seldom that, as the Russian court servant language had it, Their Majesties could sit en famille. The Emperor's day was divided according to strict unvarying rules, from the day of his accession until 1914. The Empress had to fit in her day accordingly. There were small variations to suit special places of residence, but in the main the arrangements were the same. Breakfast was about nine A.M., then followed interviews with ministers until eleven, a short turn in the garden for half an hour or so, and audiences and guests for luncheon. In such cases Their Majesties made a cercle after luncheon, which lasted till a quarter to three. Then there would be a drive with the Empress or, in later years, when her health failed, a solitary walk for the Emperor and work from four until tea, to which meal some member of the Imperial Family generally came. At a quarter to six the Emperor retired to work with his ministers again until eight. In those early days the Emperor and Empress then went to dinner with the Dowager-Empress, after which the Emperor retired once more to his study and the Empress sat with her mother-in-law. Sometimes in the evening the Emperor would find an hour to take his young wife on a sledge drive far out on "the Islands," a favorite promenade of the people of St. Petersburg. This was a delight to both, the rapid pace of the horses, the crisp snow flying under their feet, the quiet, snowy, winter landscape, were all new and fascinating to the Empress, and these were almost the only hours they had alone together. After having devoted herself whole-heartedly, first to her father and then to her brother, the Empress now centred her whole life on her husband. Her days were so mapped out as to seize any chance moment that the Emperor could give her. She was an ideal wife, and always true to her childhood's nickname of "Sunny," the name by which Nicholas II nearly always called her. She was bright and cheerful and entered into all her husband's interests, never letting him see that she was tired or worried. More and more she came to appreciate her husband's inherent chivalry of nature, his equable temper and great sense of duty and patience. More and more, too, she realised how conscientiously he set about the work which had come to him so suddenly and for which he felt himself so insufficiently prepared. But on the whole she knew very little about the Emperor's working life. He never spoke to her of political questions during that first year, nor indeed later. It was not until her son was born that she took any interest in the political life of the country. She did not think that politics were a woman's sphere. The woman's duty was to make the home, and she made a real home for her husband and children. The young Empress's household had been appointed by the Dowager-Empress: the members were all total strangers to her. Her Grande Maitresse (Mistress of the Robes), Princess Marie Mikhailovna Galitzin, was a wonderful type of old Russia, belonging by birth and marriage to the greatest families of the country. She was a grande dame of the old school, and even her outward appearance was typical of a bygone age. She had kept to the pokebonnet and caps of her youth, and always dressed in a style peculiarly her own. On State occasions this poke bonnet was ornamented with all the feathers and flowers that Victorian millinery loved. This gave rise to an amusing incident during the Imperial visit to France, when one of the pressmen came up to Count Hendrikov (a gentleman-in-waiting) and asked him what the headdress which Princess Galitzin was wearing was called, believing the poke-bonnet to be a kind of national headdress! Princess Galitzin, notwithstanding her overawing manner - she struck terror into the hearts of all the debutantes, at whom she glared through her horn glasses-was kind and straightforward. She was courteous in spite of her brusque manner, but was no diplomat and could not do much to help the young Empress, to whom she became deeply attached. Although the Empress was rather afraid of her to begin with, she afterwards loved her dearly. When Princess Galitzin died in 1910 the Empress felt her loss greatly, and said to Princess E. N. Obolensky : "J'ai perdu la plus grande amie que famis en Russie. Meme dans toute la famille, personne ne m' était aussi proche." The male household was headed by Count Paul Constantinovich Benckendorff. The Emperor's suite did not come much in touch with the Empress during the year of mourning. Mlle. Schneider came daily to read or drive with the Empress, as her Russian studies were being continued. From the Empress's notes in her husband's diaries, it can be seen that she worked hard at the language, even in the early days after her marriage. The Empress later gained great proficiency in Russian, which she spoke without any foreign accent, but for many years she was timid at starting a conversation in it, fearing to make mistakes. Living as she did under the same roof as her mother-in-law, the Empress saw much of the Empress Marie Feodorovna. She was full of sympathy for her, but as the Dowager-Empress had her much-loved sister, the Princess of Wales, staying with her at the time, she naturally needed no other consoler. In her letters of this time the young Empress speaks with tenderness of the Dowager-Empress. The temperaments and tastes of mother- and daughter-in-law were so dissimilar that, without actually clashing, they seemed each fundamentally unable thoroughly to understand the other. Later, as is natural in such cases, people of the "old court" became critical of the doings of the "young court." The idea arose that such criticisms were echoes of the Dowager-empress's opinions, and gossip was started, mostly unfounded. When, once or twice, slight friction did arise between the two Courts, society made the most of it, but the two Empresses always met on friendly terms. According to an Ukase of the Emperor Paul I, the Dowager-Empress in Russia always had precedence over the reigning Empress. On ceremonial occasions, therefore, the Empress Marie Feodorovna preceded the young Empress on the Emperor's arm, the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna following on the arm of the senior Prince. During the first years of the Emperor's reign the Dowager-Empress's influence on her son was undoubtedly considerable. If the Emperor ever spoke of the political situation and of the difficulties of government, it was not to his young and inexperienced wife, but to his mother, whose advice on general questions he had always been accustomed to seek. The young Emperor and Empress never failed in attention to the Dowager-Empress, and when they first moved into the Winter Palace they visited her nearly every day. As years went on, and the Imperial couple gave up coming to St. Petersburg for the winter, the exchange of visits grew less frequent. Still at every family féte, either the young Emperor and Empress went to the Dowager-empress or the Dowager-Empress went to Tsarskoe Selo, while Christmas always united the whole Imperial Family at the Dowager-Empress's Palace. Ten days after the wedding, the Emperor and Empress went to Tsarskoe Selo to see for themselves what alterations should be made in the old Palace that they meant to make their home. This was their real honeymoon. Their dutiful sentiment with regard to the Empress Marie can be judged by the grateful tone in which the Emperor remarks in his diary that his mother has allowed them to stay for a few days longer at Tsarskoe Selo. As to the young Empress, her feelings at this time can be seen from this note she made in the Emperor's diary, November 26th, 1894: Never did I believe there could be such utter happiness in the world-such a feeling of unity between two mortal beings. No more separations. At last united, bound for life, and when this life is ended we meet again in the other world and remain together for Eternity.The same feelings are echoed in a Christmas letter to her eldest sister, then at Malta: Dec. 15, 1894.The remainder of the year was spent partly at the Anichkov Palace, partly at Tsarskoe Selo. Both had been delighted with Tsarskoe. The Emperor's childish recollections were linked with it, and he had been born in the very bedroom they occupied during their first stay. Life in town was very irksome to the Emperor, an outdoor man to whom exercise was a necessity. Happily the Anichkov Palace had a garden and an ice-hill, and whenever he could leave his audiences and papers, the Emperor and Empress would join the young Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich and the Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna - then sixteen and thirteen-in ice-hilling or walking round the garden. The Empress was busy with plans for the renovation and decoration of the Winter Palace and Tsarskoe Selo, where she hoped to have her own home and to have the Emperor completely to herself. With the Grand Duchess Serge, who had come from Moscow, the young Empress planned changes in the old palace, and enjoyed creating her own individual setting. The Jugendstil had made its appearance at Darmstadt, and Alexandra Feodorovna's taste at that time was undoubtedly influenced by it. Her mauve boudoir, her large, pale-green sitting room, connected by a private passage in an overhanging gallery with the Emperor's study, were distinctly art nouveau.  Above: The Mauve Room The Empress's own personality was, however, clearly seen in her rooms, in the beautiful collections of ancient crosses, in the pictures on the walls - a lovely Annunciation by Nesterov in the mauve room, exquisite in colouring, watercolors of Hessian and English scenes that she had known and loved, beautiful knick-knacks and china on the tables, all chosen by her or gifts from those she loved and who knew her taste. Her friends could always guess which were the Empress's things. Pale mauve enamels (mauve was her favorite colour), transparent green nephrite cups, crystal inlaid with amethysts, bookmarks and small objects decorated with edelweiss in baroque pearls, or bearing the emblem of the Swastika, symbol of eternity-these were all stamped with the Empress's individuality. The things did not always harmonize with one another, or even with the setting. She liked a thing often more for its associations than for its beauty, for hers was a sentimental rather than an aesthetic nature. She was not a collector of antiques. She loved a homely house, with children and dogs about it. She did not like to be constantly afraid for the safety of some priceless object, and the atmosphere of her private rooms in the Palace was, above all, one of comfort. The official reception rooms were, of course, more stately. She was a lover of flowers and nature, and her rooms were always a mass of white lilac and every kind of beautiful orchid. These throve, for the Empress's rooms were always extremely cold, a trial to those unaccustomed to them. Like her grandmother, Queen Victoria, she could not stand a temperature that was even moderately warm. It sent all the blood to her head, even when she was young, and in later years when her heart trouble began she found too much warmth even more trying. The bedrooms and nurseries were all simply upholstered in bright chintzes, The Empress kept faithfully to the English ideas that had been her mother's. and these rooms were just like those in a comfortable English house. There was no wonderful luxury, but real comfort, for the Empress was eminently practical, and in planning her house saw to all the details herself; and in her home were to be found reminiscences of all her past life. |

|

Alexandra Feodorovna was the last Romanov Empress of Imperial Russia. This online book - The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feororvna was written by Countess Sophie Buxhoeveden, Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress, who served the Empress for many years and followed the Imperial family into exile. |

- Early Surroundings

- Childhood

- A Young Princess

- Engagement

- Marriage

- Her New Home

- Coronation

- Journeys

- Charities and Life

- Queen Victoria

- Foreign Trips

- Birth of Alexis

- Gathering Clouds

- On the Standart

- Rasputin

- Her Family

- Empress at Home

- Last Years of Peace

- Wartime 1914

- War Work

- Without the Emperor

- Visits to Headquarters

- Before the Storm

- Warning Voices

- Rasputin's Murder

- Revolution 1917

- Abdication of the Emperor

- Prisoners

- Five Weary Months

- Tobolsk

- Ekaterinburg 1918