This is Bob Atchison's guide to picking the best antique and old roses that do well in Austin. There are plenty of rose-stories from Bob's past

Chapter IVEngagement, 1894In the next two years the bond that had always united the young Grand Duke of Hesse and his sister became a complete and harmonious understanding. The Grand Duke looked after his sister chivalrously, and acted as father, mother and friend. The innate motherliness of the Princess's character made her happiest when she could most devote herself to others, and she now centred all her thoughts on her brother. She shared his pursuits, identified herself with his interests, and gave up her life and aspirations to him. She always did everything with her whole heart, and, in this and in the official duties that would have fallen to a Grand Duchess of Hesse, Princess Alix overtaxed her strength. The shock of her father's death and the fatigues that followed it were too much for her. She was nearing a breakdown, and had to be taken for a cure to Schwalbach by her brother, after which they went to England in August. Her cousins were continually staying with the Queen, and there was always a merry band of young people in the palace. The Queen always hoped that her granddaughter would marry in England. In 1892 Queen Victoria took Princess Alix with her when she visited the mining districts in Wales. The Princess was much interested by all she heard about the life of the miners and insisted on being allowed to go down a mine. In January 1893 Princess Alix paid her second visit to Berlin, con-ling up for the wedding of two cousins, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse and Princess Margarethe of Prussia. She fell ill there (with inflammation of the ears) and was advised to recuperate in a warmer climate. So her brother took her to Italy in the early spring of 1893. They went first to Florence, where Queen Victoria was staying at the Villa Palmieri, and then to Venice. Both were artistic and fully appreciated the beauties of Italy. Princess Alix was too busy sight-seeing with her relations, whom she met in great numbers on that trip, to write much; still she managed to send her old friend and governess, Miss Jackson, her "darling Madgie," "A few lines from your beloved Venice."

"We have been favoured with the finest weather [she wrote] so that you can imagine how enjoyable all has been. It is like a dream, so different to anything one has ever seen. And how interesting the different style of painting to the Florentines. . . . The delightful sensation of being rowed in a gondola and the peace and quiet. We used to take our tea on some island or other. . . . What a dream of beauty Florence also. . . . That view from San Miniato is too exquisite. Now we have once been here, I fear that we shall always long to come again."However much Princess Alix enjoyed the journey and shared her brother's artistic enthusiasm, throughout that year the memory of her father was constantly with her. Her life and frame of mind at this period are seen in a letter to Miss Jackson: DARMSTADT,Many princes came to Wolfsgarten during these years, and Princess Alix saw many in England, but no one had succeeded in touching her heart. She was always faithful to the Tsarevich, who had been her love at first sight. She thought of him as the hero of an ideal romance, but only her friend Toni knew what was in her heart. She knew that the wife of the heir to Russia had to be of the Orthodox faith, and to her the religious question then seemed an insurmountable obstacle. After her father's death, her conscientious scruples troubled her even more, for she had never spoken of the question to him, and now felt that she could never know what were his views. The Tsarevich had admired her greatly in 1889. Both were too young then they were only seventeen and twenty-one - for any question of marriage to arise, and the Tsarevich was still treated as a boy by his parents. They did not meet between 1889 and 1894, though they corresponded, and exchanged small gifts, and the Tsarevich heard much of Princess Alix from the Grand Duchess Serge. Both she and the Grand Duke had always wished for the marriage, and she naturally rejoiced at the idea of having her sister in Russia. She guessed Princess Alix's romance, and saw the charm that she had for the Tsarevich. Russia had quickly attracted the Grand Duchess Elizaveta Feodorovna, as she was now called. She loved the country and the people. She had made many friends and was very popular. Her husband not being in the direct succession, she could have retained the Lutheran faith, but the Orthodox Church appealed to her, and of her own free will - her husband never attempted to influence her - she became Orthodox in 1891. She did not, therefore, see the religious question as an impediment. It was a real love-match - one of those ideal unions that seem to belong to fairyland, and tales of which are handed down through the ages. Their love grew with their life together, drew them ever closer, and never abated. The Emperor's diaries and the Empress's letters to the Emperor show what they were to each other. Princess Alix sent a radiant telegram to her confidant, Toni Becker, from Coburg, in which she said she was unendlich glucklich (supremely happy), and the following letter to her old governess: PALAIS EDINBURG, COBURG,The political advantages of the marriage had never carried weight with Princess Alix. She had followed her heart, and the fact that the Tsarevich was the heir to one of the greatest Empires in the world was, as her friend, Toni Becker (Frau Bracht), said, rather in the nature of a drawback. Her relations took a more practical view. Queen Victoria, who had come to Coburg for her grandson's wedding, was very much pleased at the alliance, and did a great deal at the crucial moment to help Princess Alix with her conscientious scruples. Her voice was to the Princess the echo of that of her mother, and brought with it, too, the revered grandmother's authority. The German Emperor was also strongly in favour of the match, and, though he had never been a particularly intimate friend of either, he helped them both, by suggesting a modification of some of the antiquated formulas of renunciation, so as to lessen the religious difficulties for the Princess. There were great rejoicings at Coburg when the engagement was announced, and warm telegrams were received from the Emperor and Empress of Russia. The people of Darmstadt, too, were proud of their Princess's great marriage, though some of the older people shook their heads. Russia was far away, and the political atmosphere there always seemed heavy with menace to those who remembered the murder of Alexander II. The young Princess had no forebodings, however. She was intensely happy. The engaged couple spent a few days at Coburg, and went for a day to Darmstadt to see the Grand Duke of Hesse and his bride, and to visit the mausoleum at the Rosenhohe. Then the Tsarevich had to return to Russia, and Princess Alix, with Fraulein von Fabrice, left almost immediately for Windsor. Here Queen Victoria once more brought her influence to bear. She encouraged her granddaughter to have many serious talks with the Bishop of Ripon, Dr. Boyd Carpenter. The Bishop showed her how many were the points in common between the Orthodox Church and the Church of England, and it was decided that, on her return from a cure at Harrogate, the Emperor of Russia's confessor, Father Yanishev, should come to Windsor to instruct the Princess in the tenets of the Orthodox Church. At Harrogate, where she underwent a treatment for sciatica, Princess Alix did not lose time, for she at once began to study Russian diligently, under the guidance of Mlle. Catherine Adolfovna Schneider,- reader to her sister, the Grand Duchess Serge. "It is amusing, but certainly not easy!" Princess Alix wrote to Miss Jackson about these Russian lessons. The Princess lived very quietly at Harrogate under the name of Baroness Starckenburg, but her incognito was soon discovered, much to her chagrin, and she had great difficulty in escaping from the notice of the public, whose interest was sometimes very embarrassing. She did not go about much on account of her cure, but her small niece, Princess Louis of Battenberg's daughter, was with her. So full of interest was the Princess in everyone and everything about her that, when the landlady at her lodgings had twins, she insisted on standing sponsor in person, the children being appropriately named Nicholas and Alexandra. Meanwhile the Tsarevich was waiting impatiently to see his fiancée again, and as soon as the Princess's cure was over he set off for England. The Princess was then staying with her sister and brother-in-law, Prince and Princess Louis of Battenberg, at Walton-on-Thames, and there the engaged couple spent a few happy days. Then they went to Windsor, where they met all the members of the Royal Family, received congratulations and saw numerous visitors, among them being the aged Empress Eugénie, who had been a friend of the Grand Duchess Alice, and in 1883 had come to see Prince Ernest Louis and Princess Alix, when they were quite by themselves at Darmstadt. The little Princess had entertained her charmingly, and had been presented as a reward with a beautiful doll by the Empress - too beautiful to play with, alas! The Tsarevich's simple, engaging manner endeared him to those of the Princess's relations who had not yet met him. Physically he was very much like his cousin, the Duke of York (King George V), and this produced many amusing mistakes. When the Tsarevich was in England for the Duke's wedding in 1893, many of the guests at a garden party shook him warmly by the hand, with effusive congratulations, taking him for his cousin the bridegroom. The greatest joke, however, was when one of the gentlemen of the Court made the contrary mistake, and coming up to the Duke, whom he took for the Tsarevich, begged him not to be late for the wedding the next day. As it was the Duke's own wedding, it is probable that he was punctual! While the Tsarevich and Princess Alix were at Windsor the present Prince of Wales was born, and the Tsarevich was one of his sponsors. Between rides, tea parties, and dinners, Father Yanishev began his tuition, but it was decided that this had better be continued at Darmstadt. The Queen took her grandchildren about herself, like any other proud grandmother. It was an idyllic time for the Princess, and she always cherished memories of Windsor, and of the brief moments when she and her fiancé were together. The Queen had strict ideas on chaperonage and never left the engaged couple alone, which must sometimes have been rather trying for the Tsarevich! He had brought Princess Alix beautiful presents, both from himself and from his father and mother. The pink pearl ring that the Empress always wore was her engagement ring. Her chain bracelet, with a huge emerald, was a present given by the Tsarevich at Windsor, as was a necklace of pink pearls; and the Emperor of Russia sent a marvellous sapphire and diamond brooch. The Empress used to say that when Queen Victoria saw all these splendors, so different from the simple jewellery of her own youth, she would say to her granddaughter, as if she were still a child, "Now, do not get too proud, Alix." From Windsor the Queen took the Tsarevich and his fiancée to Osborne. Their stay there could only be short, as the Tsarevich had to leave for Russia so as to be present at the wedding of his sister, the Grand Duchess Xenia. From the Emperor's diaries of the time, it is easy to see how their love was always growing, and how hard the separation was to both. After her brief sojourn at Osborne the Princess returned to Darmstadt, and set about diligent preparations for the marriage, which was planned for some time in the following spring. She worked assiduously with Mlle. Schneider, and continued her studies with Father Yanishev. She went into the religious question with the utmost thoroughness. Indeed, Father Yanishev told the Grand Duke of Hesse that the Princess used to ask him questions on abstruse points of theology such as he had never heard even from theologians, and that she often had him in a corner, when, to quote his own words in somewhat hazy German, he could only "scratch like a cat " (kratzen wie eine Katze) without finding an answer. Meanwhile, disquieting reports began to come concerning the health of the Emperor of Russia. Years of work had sapped his strong constitution, and the army manoeuvres in the autumn, which he insisted on attending, had further aggravated his illness. The doctors ordered him rest and an immediate departure for the Crimea. The state of his father's health obliged the Tsarevich to put off his proposed visit to Darmstadt, and soon his letters to his fiancée became more and more despondent. Princess Alix was greatly distressed at not being with him at such a time. She knew his devotion to his father and could picture to herself his state of mind. At the beginning of October he telegraphed, summoning Princess Alix to the Crimea. Princess Louis of Battenberg went with Princess Alix to Warsaw, where the sisters parted, Princess Louis returning to Malta, and Princess Alix, with Baroness Grancy, continuing the journey alone. On the way south, the Grand Duchess Serge joined her, and on October 23rd she arrived at Simferopol and was met by the Tsarevich. Princess Alix and he drove in an open carriage the eighty versts between that town and the Imperial residence, Livadia, the Grand Duchess following in another carriage. The whole Imperial Family were gathered at Livadia, for it was realised that the sands of the Emperor's life were running out. He insisted, however, on getting up and dressing to do honour to his heir's bride, and greeted the Princess with the greatest kindness. In the lovely Livadia chapel the Princess took part in her first Russian Church service - one of intercession for the Emperor. There are a few lines written by her in the Tsarevich's diary at that time which speak of this: "I have been able to pray with you in church for your darling father. What a comfort! You near me, all seems easier. I know you will always help me." Princess Alix had wired to the Tsarevich at the Russian frontier her intention of joining the Orthodox Church on her arrival at Livadia - news which, as he notes in his diary, had given him great joy. The whole palace was under the influence of the angel of death. The family scarcely dared leave the house for fear of a sudden collapse. The end came on November 1st. In the presence of the whole Imperial Family and of the Princess Alix, Father John of Kronstadt read the last prayers to his dying Sovereign. The Emperor Alexander III passed away: the Tsarevich was the Emperor Nicholas II. |

|

Alexandra Feodorovna was the last Romanov Empress of Imperial Russia. This online book - The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feororvna was written by Countess Sophie Buxhoeveden, Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress, who served the Empress for many years and followed the Imperial family into exile. |

- Early Surroundings

- Childhood

- A Young Princess

- Engagement

- Marriage

- Her New Home

- Coronation

- Journeys

- Charities and Life

- Queen Victoria

- Foreign Trips

- Birth of Alexis

- Gathering Clouds

- On the Standart

- Rasputin

- Her Family

- Empress at Home

- Last Years of Peace

- Wartime 1914

- War Work

- Without the Emperor

- Visits to Headquarters

- Before the Storm

- Warning Voices

- Rasputin's Murder

- Revolution 1917

- Abdication of the Emperor

- Prisoners

- Five Weary Months

- Tobolsk

- Ekaterinburg 1918

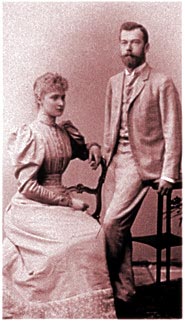

Left: Alexandra and Nicholas in Germany at the time of their engagement

Left: Alexandra and Nicholas in Germany at the time of their engagement