Olson Defendorf Custom Homes wins prestigious design award from Houzz.

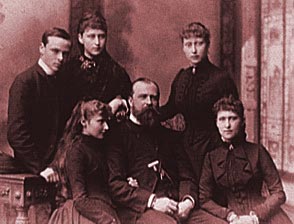

Chapter IIChildhood, 1879-1888 Princess Alix used to say, in after years, that her earliest recollections were of an unclouded, happy babyhood, of perpetual sunshine, then of a great cloud. . . . The Grand Duchess Alice's death left an inexpressible void in the Palace. It took a long time before those in it could adjust themselves to a life which had lost the hand that guided it. The Grand Duke Louis IV had scarcely recovered from his own severe illness at the time of his wife's death. All the children were moved as soon as possible into the cold, unfamiliar surroundings of the old town-Schloss, and from its windows poor little Princess Alix, then barely six, saw her mother's funeral procession wending its way from the New Palace to the family mausoleum at the Rosenhohe. The Grand Duke did all in his power to take his wife's place with his motherless children. He was a kind-hearted, honest man, with a wonderfully fair outlook on things and events, and was adored by his children. Naturally he spoilt the youngest a little: Princess Alix seemed so lonely and desolate without her small playfellow, Princess May. The Grand Duchess Alice had always had the entire management of the children's education, and after her death the Grand Duke scrupulously followed the directions she had given. She was no more, but her influence remained. The Princesses' governesses consulted the Grand Duke on minor details, but in essentials followed his wife's ideas. From this time, too, Queen Victoria took a special interest in her orphaned grandchildren. Both Miss Jackson and Prince Ernest Louis's tutor had to write monthly reports to the Queen, whose autograph answers to Miss Jackson show that she went into every small detail and often gave definite directions. These letters express the Queen's ideas on feminine education. They may strike the reader as old-fashioned, but Miss Jackson, while keeping in the main lines to the Queen's sound advice, evidently adapted them to the exigencies of more modern times.  The Grand Duke with his children, clockwise from left, Ernest-Louis, Elizabeth, Irene, Victoria, Grand Duke Louis, and Alix (Alexandra) The first months after her mother's death were untold misery and loneliness for Princess Alix, and probably laid the foundations of the seriousness that lay at the bottom of her character. She was now quite alone in the nursery. Even Prince Ernest Louis, who was now ten, had a tutor to keep him at lessons all day, and Princess Irene, who was six years older, had joined the elder Princesses in the schoolroom. Princess Alix long afterwards remembered those deadly sad months when, small and lonely, she sat with old "Orchie " in the nursery, trying to play with new and unfamiliar toys (all her old ones were burned or being disinfected). When she looked up, she saw her old nurse silently crying. The deaths of her beloved Grand Duchess and of Princess May had nearly broken her faithful heart. Until this time Princess Alix had been on the whole a merry child. She was hot-tempered and ardently desired things, though she showed great self-restraint even at an early age. She was generous, and even in her babyhood incapable of any childish falsehood. She had a warm and loving heart; was obstinate and very sensitive. A chance word could hurt her, but, even as a small girl, she did not show how deeply she had been wounded. This was her childhood's character, and in many traits it shows the future woman. Queen Victoria, who loved the Grand Duke of Hesse as a son, urged him to come to her with all his children as soon as possible, and in January 1879 the family went to Osborne for a long stay. Here by degrees they recovered, mentally and physically, and returned to Darmstadt two months later, accompanied by Prince Leopold (Duke of Albany). He had always been a favorite uncle. The two elder Princesses tried to take their mother's place as their father's companions, and were constantly with him. The sixteen-year-old Princess Victoria looked after her brother and sisters, and acted as mistress of the house. The Grand Ducal family went that first year to Schloss Wolfsgarten, and the new surroundings and the elasticity of youth helped the children to recover their vitality. They returned to the New Palace in the winter of 1879-1880, and Princess Alix began her solitary schoolroom life. She had toiled at her spelling under faithful Orchie's eye; now came the somewhat formidable Fraulein Anna Textor, a connection of Goethe himself, who, under Miss Jackson's general guidance, carried on her education. Miss Margaret Hardcastle Jackson, "Madgie" as the Princess Alix affectionately called her later, was a broadminded, cultivated woman, who soon gained a strong influence over her pupils, particularly the eldest. She had impressed the Grand Duchess Alice by her advanced ideas on feminine education. She tried not only to impart knowledge to her pupils, but to form their moral characters and widen their views on life. A keen politician, she was always deeply interested in all important political and social questions of the day. Young as they were, Miss Jackson discussed all such matters with the children, awakening their interest in intellectual questions. Gossip of any kind was not allowed by her. The Princesses were trained to talk on abstract subjects. It was unfortunate that Miss Jackson felt too old and tired, and had to retire before having quite finished the Princess Alix's education, when her youngest charge was only fifteen, as she would certainly have been able to accustom her to break through her reserve and acquire a simpler and easier outlook on life. With the thoroughness that ever characterized her, Princess Alix gave her whole energy to her lessons. She always had a strong sense of duty, and her teachers certify that she would always willingly give up any pleasure that she thought might prevent her finishing some task for next day. Samples of her handwriting at seven years old show it to be wonderfully neat and firm, and she had a very retentive memory. By the time she was fifteen, she was well grounded in history, literature, geography and all general subjects, particularly those relating to England and Germany. According to her letters to her eldest sister, she toiled without a murmur at dry works like Guizot's Reformation de la Litterature, the Life of Cromwell and Raumer's Geschichte der Hohenstaufen in nine volumes: compared with these, Paradise Lost, which she read in the intervals, must have seemed quite light reading! She had a French teacher, and though her accent was fair, she never became thoroughly at home in that language and always felt "cramped," as she said, in it, being at a loss for words. This hampered her later in Russia, where French was the official language at Court. English was, of course, her natural language. She spoke and wrote it to her brother and sisters, and later to her husband and children and to all those she knew well. Princess Alix had one of those sensitive natures that respond most readily to music. She "adored" Wagner and the classics, and when she grew up attended every concert within her reach. Her music teacher was a Dutchman, W. de Haan, at that time Director of the Opera at Darmstadt, who greatly praised her musical ability. She played the piano brilliantly, but her shyness made her extremely self-conscious whenever she played before people. She told the author of the torment she endured when Queen Victoria made her play in the presence of her guests and suite at Windsor. She said her clammy hands felt literally glued to the keys and that it was one of the worst ordeals of her life. She did not excel in drawing, but was a good needlewoman and designed attractive trifles, which she gave to her friends or to charity bazaars. Her interest in art in general developed later under her brother's influence. The Grand Duke Louis IV was much with his children, and in summer liked to take them about with him to functions in different towns, or to manoeuvres. Princess Alix had a very great love for her father, and her delight knew no bounds when she was included in these expeditions. She loved her picturesque "Hessenland." She cherished recollections of her childhood and early youth, and always in her mind separated Hesse completely from the rest of Germany, which she looked on as Prussia and as a different country. She went to Berlin only twice on short visits before her marriage. Nearly every autumn the Grand Duke of Hesse took his children to Windsor or Osborne, or more often, to Balmoral, for he was a keen sportsman and good shot. These visits were the best part of the year to his youngest daughter. They developed her mentally, too, as they brought her into contact not only with her cousins, but with all the Queen's entourage, politicians and notabilities of all sorts. Listening to their conversation at luncheon, her interest in matters beyond her years was unconsciously awakened, and at thirteen Princess Alix looked and spoke like a much older girl. Her English point of view on many questions in later life was certainly due to her many visits to England at this most impressionable age. The Grand Ducal family looked upon themselves almost as a branch of the English royal house. They felt one with it, and took part in all the family festivals. In 1885 Princess Alix's holidays were hurried on to enable her to act as bridesmaid to her aunt, Princess Beatrice, who married Prince Henry of Battenberg, On July 23rd, 1885. This was of course a great event to the thirteen years old Princess. At Wolfsgarten the Grand Ducal family had frequent visits from their English relations : the Prince of Wales (King Edward VII), the Marquess and Marchioness of Lorne (Princess Louise), the Duke of Albany and, most often, Prince and Princess Christian, whose children, Princesses Marie Louise and Helena Victoria, were great friends of Princess Alix. The younger children of the Crown Princess - of Germany (later Empress Frederick), the Princesses Sophie and Margarethe, now Queen-Dowager of Greece and Landgravine of Hesse, also came often to Wolfsgarten. The elder Princesses were fast growing into womanhood. Princess Victoria and Princess Elizabeth (Ella) came out in 1881, but Princess Alix only heard echoes of their gay doings. She had been promoted to share the schoolroom with fifteen-years-old Princess Irene, but the latter had her own friends, and Princess Alix was still much by herself. In her immediate surroundings, her two ladies had most certainly a part in the development of Princess Alix's character. These were Baroness Wilhelmine Senarclens Grancy, lady-in-waiting to the four Princesses, and later Princess Alix's own lady, Fraulein Margarethe (Gretchen) von Fabrice. Baroness Grancy was a woman of the old school, upright, honourable, kind, if perhaps a trifle strict. She was a real friend to the family, and dearly loved little Princess Alix, to whom, as to all, she did not refrain from occasionally giving a bit of her mind. The wiry, hardy, little, old lady was incapable of any insincerity, and the embodiment of duty. Never allowing herself a moment's relaxation, she always preached that "one must pull oneself together," and not give in, either physically or morally; and she inculcated this principle into Princess Alix, who was always very hard with herself all her life. Her outward manner was short and abrupt, and, in those early years, Princess Alix may have felt her more of a mentor than a friend. Fraulein von Fabrice was appointed Princess Alix's special lady-in-waiting when the Princess was sixteen, and she herself was in her twenties. She had lived in England as governess to Princess Christian's daughters. Fraulein von Fabrice's aim was to guide the Princess. She had high and lofty ideals and was very religious, but, as she was shy herself, she could not help the Princess to fight against her timidity. Her idealism certainly influenced Princess Alix, who formed a great friendship with her, though she soon became reticent in speaking of the things that touched her deeply, fearful of her too demonstrative sympathy. Toni Becker, her childhood's friend, was allowed sometimes to share her thoughts, and the young hereditary Grand Duke Ernest Louis, when he was at home, shared many more. He was the only real friend of her youth, and their childhood's love and understanding deepened as the difference in their ages was equalised by time; and when he went to the University she missed him sorely, for she was again alone. In 1884 there was great excitement among the young people at the Darmstadt palace, for their eldest sister, the Princess Victoria, who had always ruled the nursery and had mothered her younger sisters so capably since their mother's death, became engaged to her cousin, Prince Louis of Battenberg. The wedding festivities took place at Darmstadt on April 30th, 1884; Queen Victoria, the Prince and Princess of Wales, and the German Crown Prince and Crown Princess being present. The young Princesses were so much excited by the event that this first break in their family circle had no sadness in it, particularly as Princess Victoria promised to return to Darmstadt whenever her sailor husband was at sea. No sooner had the excitement of this wedding abated, than preparations began for the marriage of the second Princess, Elizabeth, who had been engaged for some time to the Grand Duke Serge, a brother of the Emperor Alexander III of Russia. Princess Elizabeth had known the Grand Duke from childhood, as he had often stayed for months at a time at Jugenheim with his mother, the Empress Marie Alexandrovna, wife of Alexander III. The Princess Elizabeth (Ella) was a very pretty girl, tall and fair, with regular features. She was the personification of unselfishness, always ready to do anything in order to give pleasure to others. She was cheerful, with a strong sense of humour, and as a child always the peacemaker in nursery and schoolroom, a favorite with all her sisters and brothers, and a link between them. After a visit to England in the spring of 1884, the whole Grand Ducal family went to St. Petersburg for Princess Ella's marriage. Princess Alix, who was only twelve at the time, was full of joy and anticipation at the idea of the journey. Travelling up the long ugly stretches of country from the Russian frontier to St. Petersburg, Princess Alix's impressions of what was to be her country also cannot have been very thrilling ones. But, happily, she was interested in everything, and all the young people arrived in a very cheerful mood at Peterhof, then the residence of the Russian Court. The future Grand Duchess made her state entrance into the capital in a gilt coach drawn by white palfreys which were led by gold-liveried servants. At St. Petersburg the gorgeous marriage ceremonies took place, followed by many festivities, in which Princess Alix, to her chagrin, did not take part. But she was rewarded by the few delightful days that the whole family spent afterwards in Peterhof, where, for the first time, she met her future husband, the Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich, and his brothers and sisters. The band of young people amused themselves in the gardens and went sight-seeing together, Princess Alix the keenest among them. She could always join in fun thoroughly and could laugh at some joke till the tears streamed down her cheeks, even in later days, but it was never in her to set the laughter going. Leave-takings from the Grand Duchess Serge were sadder than those from Princess Victoria. The elder sister had her parents-in-law in Hesse, and there was the prospect of seeing her often, while the distance from Russia was great. The family circle was reduced that winter at Darmstadt. It was made still smaller by the death of the Grand Duke's mother, old Princess Charles. She had many sorrows and lived a very retired life in her own palace at Darmstadt, devoting much of her time to charitable works; but she had been very kind to her motherless grandchildren, and was sincerely mourned by them. In the spring of 1885 the Grand Duke and Grand Duchess Serge came to Wolfsgarten and spent part of the summer there. Prince and Princess Louis of Battenberg soon joined them with their baby daughter, Princess Alice (Princess Andrew of Greece), a delightful toy for Princess Alix. This was the first of a series of happy family meetings that were to take place nearly every year. The Grand Duke Serge was much liked by his wife's family. He was a real grand seigneur, of high culture, artistic temperament and intellectual pursuits, though a certain shyness made him seem outwardly stiff and unresponsive. He took a great liking to little Princess Alix, whom he very much admired. He used to tease her unmercifully, and often reduced her to a state of blushing confusion, which she really rather enjoyed. The Grand Duke of Hesse was always ready to join in his children's fun and liked going about with his four pretty daughters. Princess Irene was now acting as hostess for her father. Princess Alix used sometimes to be allowed as a great treat to appear at thés dansants which were given for Princess Irene, and in the years 1886-1887 she began to see something of the young people of Darmstadt. The latter year was marked by Queen Victoria's jubilee celebrations, to which the Grand Duke took his two youngest daughters. But as Princess Alix was not "out," much to her regret, she saw only the procession in the streets. |

|

Alexandra Feodorovna was the last Romanov Empress of Imperial Russia. This online book - The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feororvna was written by Countess Sophie Buxhoeveden, Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress, who served the Empress for many years and followed the Imperial family into exile. |

- Early Surroundings

- Childhood

- A Young Princess

- Engagement

- Marriage

- Her New Home

- Coronation

- Journeys

- Charities and Life

- Queen Victoria

- Foreign Trips

- Birth of Alexis

- Gathering Clouds

- On the Standart

- Rasputin

- Her Family

- Empress at Home

- Last Years of Peace

- Wartime 1914

- War Work

- Without the Emperor

- Visits to Headquarters

- Before the Storm

- Warning Voices

- Rasputin's Murder

- Revolution 1917

- Abdication of the Emperor

- Prisoners

- Five Weary Months

- Tobolsk

- Ekaterinburg 1918

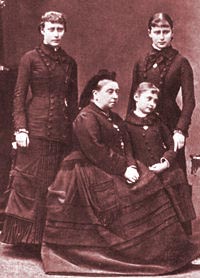

Left: Queen Victoria with Princess Victoria, Elizabeth and Alix of Hesse, in 1879.

Left: Queen Victoria with Princess Victoria, Elizabeth and Alix of Hesse, in 1879.