Chapter Twenty - In Prison

In the morning the commisars presented themselves: the two who brought us and a new one, Beloborodov. They entered the second class carriage and asked all those inside to leave the train and to get into the izvostchiks which they had brought.

Nagorny appeared first helping the Tsarevich to get down, the grand duchesses followed. Nagorny, having put the Tsarevich into a carriage, went back to the train car wanting to help the grand duchesses carry their luggage. However the commisars prevented this. They got into the carriages with the members of the Imperial Family and left for the Ipatiev house. A half hour later they came back in the same carriages. Commisar Rodionov approached the train car and asked: "Is Volkov there?"

"I am here" I replied.

I got out carrying my valise with a pail of preserves, but they told me to leave it, under the pretext that they would bring it to me later (I never saw it again).

From the train car also got down: Gen. Tatischev, Countess Hendrikova, Miss Schneider, the cook Kharitonov and young Sednev. They got us to get into the carriages and drove us to a house surrounded by a very high fence, which made me think the Imperial Family was shut up in there. I found myself in the first carriage alone with the driver.

We were stopped in front of the house: I saw they were waiting for something. No one came out of the house, and they did not ask us to get out. They only took Kharitonov and young Sednev. The rest of us were driven much further.

I asked the isvostchik: "Where are you taking me?"

The izvostchik said nothing. I asked him the same question a second time, adding: "Is it very much farther?"

More silence. We had arrived in front of a house, Commissar Beloborodov get out of his carriage and shouted: "Open the door and receive the prisoners."

That order explained to us quite clearly where we had been brought.

They lead us into the office where we were registered; Gen. Tatischev, in the midst of the silence said to me: "That old saying is true Alexei Andreievich: Disown neither the beggar nor the prison."

"Thanks to tsarism" added Commissar Beloborodov, who had heard the Tatistchev's joke, "I was born in a prison."

After we had been written down into the prison register, they went and searched our luggage, but they did not make us open the bags and they took them away promising to bring them back later. They led us to separate cells: Misses Hendrikova and Schneider in the cell for the sick, and Gen. Tatischev and I in a cell elsewhere, on the upper floor. The next day, they brought into our cell the Emperor's personal valet, Tchemodorov, from the Ipatiev House. They held us in the political prisoners' section of the prison, where they had held the hostages.

While we were crossing the corridor, we heard a question asked by an unseen person: "Who are they bringing?" (We learned later that he had taken us to be English, due to the raincoats of English manufacture from abroad which the General and I were wearing.)

Tatischev replied: "We come from Tobolsk".

An answer was heard: "Understood."

On many occasions we asked again and again for our luggage which they had taken, but despite their promises, they were never brought; neither Tatischev nor I ever got back our things.

In the prison, in addition to the "Smotritel" (Director), there was also a commissar who authorized us, Tatischev and me, to send out for provisions to eat, at our own expense, We refused it: me, I did not have any more money; Tatischev had some, but the money he had belonged to the Imperial Family. Some time before we had received a little money sent to us to go to the assistance of the Imperial Family (the Serbian minister in Petrograd, Spalaykovich, had gotten a letter from Tatischev in Tobolsk, who told him about the position in which the Tsar and his family had found themselves. Spalaykovich immediately sent a Serbian officer, Maximovich, assigned to bring Tatistchev 75,000 rubles. Maximovich tried in vain to see the Emperor in Yekaterinburg.)

General Tatistchev and Prince Dologoruky, had divided what remained unspent equally between them, to more securely safeguard the money from the searches which were a constant fear given our living conditions, as well as from theft.

News from the Ipatiev house was brought to us accidentally by the doctor of our prison, who would see Dr. Derevenko from time to time, and who would get news about the Tsarevich's health from him.

Towards May 25 (old style), two watchmen came into our cell and asked Tatischev to follow them to the prison office, telling him that an armed guard was waiting for him there. Tatistchev went pale. The watchmen showed him a paper, on which it said that he was "expelled from the territory of the Ural region."

We said our goodbyes, and they took him. He left me his fine fur overcoat, asking me to take it to his aunt whom he loved greatly. I thought that it would be quite difficult for me to keep the overcoat safely, so I said to him that it would be more useful to Tatischev himself, believing that they were actually going to deport him. I had time to return the fur overcoat to him while he was still in the prison office.

The next day the guard's wife recounted that Tatistchev had been shot, near the prison itself: she recognized him by his English raincoat. Wanting to have the precise identification, we asked the director of the prison who informed us, in his turn, by means of the doctor. The doctor promised to personally assure the identity of the body. Having examined the corpse of the man shot, the doctor did not recognize him as being Tatistchev. I have never since then had any information about Tatistchev's fate: was he murdered in Perm or elsewhere, I do not know.

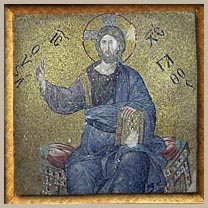

We stayed alone. Tchemodurov and I. The soon brought a prisoner, a priest, into our cell. They took us to church every Sunday, where the prisoner priest officiated. The service was conducted with great piety and solemnity at the same time, but the sadness never ceased to impose itself on one's spirit and soul, with the sight of the parents and relatives who were crying over the fate of the detainee...Black thoughts oppressed us.

Rumors spread that the "Whites" were advancing, the commissars demanded that the detainees and hostages who know a trade - shoemakers, tailors - to work for them: clothes, shoes. They paid these employees three months in advance. They set free several common law criminals of no real importance. They set free some of the hostages. We ourselves continued to be imprisoned.

The moment came when they began to evacuate the political prisoners by convict trains, in the direction of the west.

Comments on this site should be directed to Bob Atchison.