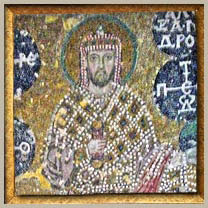

Here's a page I wrote that is dedicated to the very hard to find mosaic in the upper gallery of Hagia Sophia of the Byzantine Emperor Alexander - Alexandros

Travels Abroad, Palace Life

These yearly visits to the Crimea were diversified with holiday voyages on the Standart and visits to relatives and close friends in various countries. In 1910 their Majesties visited Riga and other Baltic ports where they were royally welcomed, afterwards voyaging to Finnish waters where they received as guests the King and Queen of Sweden. This was an official visit, hence attended with considerable ceremony, exchange visits of the Sovereigns from yacht to warship, state dinners and receptions. At one of these dinners I sat next the admiral of the Swedish fleet, who was much depressed because during the royal salute to the Emperor one of his sailors had accidentally been killed.

In the autumn of 1910 the Emperor and Empress went to Nauheim, hoping that the waters would have a beneficial effect on her failing health. They left on a cold and rainy day and both were in a melancholy state, partly because of separation from the beloved home, and partly because of the quite apparent weakness of the Empress. On her account the Emperor showed himself deeply disturbed. "I would do anything," he said to me, "even to going to prison, if she could only be well again." This anxiety was shared by the whole household, even by the servants who stood in line on the staircase saying their farewells, kissing the shoulder of the Emperor and the gloved hand of the Empress.

I heard almost daily from Frieberg, where the family were stopping, letters from the Emperor, the Empress, and the children, telling me of their daily life. At length came a letter from the Empress suggesting that I join my father at Hamburg, not far distant, that we might have opportunity for occasional meetings. As soon as I arrived I telephoned the chateau at Frieberg, and the next day a motor car was sent to fetch me. I found the Empress improved in health but looking thin and tired from the rather rigorous cure. The Emperor, in his civilian clothes, looked unfamiliar and strange, but he wore the conventional citizen's garb because he as well as the Empress wished to remain as far as possible private persons. When the health of the Empress permitted she, with Olga and Tatiana, enjoyed going unattended to Nauheim, walking unnoticed through the streets, and gazing admiringly into shop windows like ordinary tourists. Once the Emperor and the young Grand Duchesses. motored over to Hamburg and for a short hour walked about quite happily unobserved. Only too soon, however, the Emperor was recognized and our whole small party was obliged to flee precipitously before the gathering crowds and the ever enterprising news photographers. On some of our outings the Emperor was more fortunate. Once when we were wandering along a country road on the outskirts of Hamburg a wagon passing us dropped suddenly into the road a heavy box. The carrier, try as he would, could not succeed in lifting the box back to its place until the Emperor went forward and, exerting all his strength, helped the man out of his difficulty. The carrier thanked his Majesty with every expression of respect and gratitude, recognizing him as a gentle. man but never dreaming, of course, of his exalted station. To my expressions of amused enjoyment of the situation the Emperor said to me gravely: "I have come to believe that the higher a man's station in life the less it becomes him to assume any airs of superiority. I want my children to be brought up in this same belief."

Soon after this I returned to Russia to visit my sister, who had just borne her first baby, a little girl named for the Grand Duchess Tatiana, who acted as godmother for the child. My stay was not long, as letters from the Empress called me to Frankfort in order to be near her. On my arrival at Frankfort a surprise awaited me in the form of an invitation from the Grand Duke Ernest of Hesse to stay with his Imperial guests at his castle. At the castle gates I was welcomed by Mme. Grancy, the charming hofmistress of the Hessian Court, and by Miss Kerr, a bright and clever English girl, maid of honor to Princess Victoria. Miss Kerr took me at once to my apartments, near her own, and I quickly made myself at home. That night at dinner I sat between the Emperor and our host, the Grand Duke of Hesse. The company, which was most distinguished, included Prince Henry of Prussia, who that evening happened to be in rather a disagreeable mood, Princess Irene, Princess Victoria of Battenberg, and her beautiful daughter Princess Louise, Prince George of Greece, and the two semi-invalid sons of Prince and Princess Henry. The Empress was not present, being excused on account of her cure. Besides, it was understood that the Empress almost never appeared at state dinners.

The Grand Duke of Hesse I have always liked extremely both for his amiable disposition and for his many accomplishments. He was, and is still, an unusually gifted musician, a painter, and an artist craftsman seriously interested in the great pottery in Darmstadt, where his own designs are used. He has always been a man of liberal social ideals and his popularity among the people of Hesse not even the German Revolution has been powerful enough to overthrow. His wife, Princess Eleanor, when I knew her, was dignified and gracious and gifted with a genuine talent for dress. Prince Henry of Prussia, brother of the Kaiser and brother-in-law of the Empress, was a tall and handsome man, but inclined to be-let us say - temperamental. At times he was overbearing and very satirical, and at others friendly and charming. His wife was a small woman, simple in manner and of a kindly, unselfish nature. Princess Alice, daughter of Princess Victoria of Battenberg and wife of Prince Andrew of Greece, was a beautiful woman but unhappily quite deaf.

The Castle of Frieberg, which stands on a high hill overlooking a low valley and the little red-roofed town of Nauheim, is an ancient structure not particularly attractive either inside or out. There was nothing much for Grand Duke Ernest's guests to do in the way of amusement except to walk and drive. Of the Empress I saw rather less than we had planned, but sometimes late in the evenings the Emperor, the Empress, and myself met for Russian tea and for familiar talks before bedtime.

In October or November their Majesties returned to Tsarskoe Selo, the Empress greatly benefited by her cure. How happy we were to be once more at home, the Empress in her charming boudoir hung with mauve silk and fragrant with fresh roses and lilacs, I in my own little house which I dearly loved even though the floors were so cold. The opal-hued boudoir of the Empress, where we spent a great deal of our time, was a lovely, quiet place, so quiet that the footsteps of the children and the sound of their pianos in the rooms above were often quite audible. The Empress usually lay on a low couch over which, hung her favorite picture, a large painting of the Holy Virgin asleep and surrounded by angels. Beside her couch stood a table, books on the lower shelf, and on the upper a confusion of family photographs, letters, telegrams, and papers. It was undeniably a weakness of the Empress that she was not in the least systematic about her correspondence. Intimate letters, it is true, she answered promptly, but others she often left for weeks untouched. About once a month Madeleine, the principal maid of the Empress, would invade the boudoir and implore her mistress to clear up this heap of neglected correspondence. The Empress usually began by begging to be left alone, but in the end she always gave in to the importunities of the invaluable Madeleine. The Empress of course had a private secretary, Count Rostovsev, but it was one of her peculiarities that she preferred to handle her letters and telegrams before her secretary, and he seemed to accustom himself with ease to her dilatory ways.

It would be difficult to imagine two people more widely different on points of this kind than Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna. Their private apartments were very close together, the Emperor's study, billiard and sitting room and his dressing room with a fine swimming bath, almost adjoining the apartments of the Empress. The big antechamber to the study, well furnished with chairs and tables and many books and magazines, looked out on a court, and here people who had business with the Emperor waited until they were summoned to his private room. The study was a perfect model of orderliness, the big writing table having every pen and pencil exactly in its place. The large calendar also with appointments written carefully in the Emperor's own hand was always precisely in its proper place. The Emperor often said that he wanted to be able to go into his study in the dark and put his hand at once on any object he knew to be there. The Emperor was equally particular about the appointments of his other rooms. The dressing table in the white-tiled bathroom, separated from the sitting room by a corridor and a small staircase, was as much a model of neatness as the study table, nor could the Emperor have tolerated valets who would not have kept his rooms in a condition of perpetual good order. Of course the ample garderobes, where the gowns, wraps, hats, and jewels of the Empress and the innumerable uniforms of the Emperor were kept, were always in order because they were in the care of experienced servants and were rarely if ever visited by others than their responsible guardians.

The Emperor's combined billiard and sitting room was not very much used because the Emperor spent most of his leisure hours in his wife's boudoir. But it was in the billiard room that the Emperor kept his many albums of photographs, records of his reign. These albums bound in green with the Imperial monogram, contained photographs taken over a period of twenty years. The Empress had her own albums full of equally priceless records, priceless from the historian's standpoint at any rate, and each of the children had their own. There was an expert photographer attached to the household whose only duty was to develop and print these photographs, which were, in almost every case, mounted by the royal photographer's own hand. This work used to be done, as a rule, on rainy days, either in the palace or on board the Standart. The Emperor, as usual, was neater about this work of pasting photographic prints than any other member of the household. He could not endure the sight of the least drop of glue on a table. As might be expected of so orderly a person the Emperor was slow about almost everything he did. When the Empress wrote a letter she did it very quickly, holding her portfolio on her knees on her chaise longue. When the Emperor wrote a letter it was a matter of hours before it was completed. I remember once at Livadia the Emperor retiring to his study at two o clock to write an important letter to his mother. At five, the Empress afterwards told me, the letter remained unfinished.

The private life of the Imperial Family in these years before the War was quiet and uneventful. The Empress never left her room before noon, it being her custom, since her illness, to read and write propped up on pillows on her bed. Luncheon was at one o'clock, the Emperor, his aide-de-camp for the day, the children, and an occasional guest attending. After lunch eon the Emperor went at once to his study to work or to receive visitors. Before tea time he usually went for a brisk walk in the open.

At half past two I came to the Empress, and if the weather was fine and she well enough, we went for a drive or a walk. Otherwise we read or worked until five, when the family tea was served. Tea was a meal in which there was never the slightest variation. Always appeared the same little white-draped table with its silver service, the glasses in their silver standards, and for the rest simply plates of hot bread and butter and a few English biscuits. Never anything new, never any surprises in the way of cakes or sweetmeats. The only difference in the Imperial tea table came in Lent, when butter and even bread made with butter disappeared, and a small dish or two of nuts was substituted. The Empress often used gently to complain, saying that other people had much more interesting teas, but she who was supposed to have almost unlimited power, was in reality quite unable to change a single deadly detail of the routine of the Russian Court, where things had been going on almost exactly the same for generations. The same arrangement of furniture in the state rooms, the same braziers of incense carried by footmen in the long corridors, the same house messengers in archaic costumes of red and gold with ostrich-feathered caps, and for all I know the same plates for hot bread and butter on the same tea table, were traditions going back to Catherine the Great, or Peter, or farther still perhaps.

Every day at the same moment the door opened and the Emperor came in, sat down at the tea table, buttered a piece of bread, and began to sip his tea. He drank every day two glasses, never more, never less, and as he drank he glanced over his telegrams and newspapers. The children were the only ones who found tea time at all exciting. They were dressed for it in fresh white frocks and colored sashes, and spent most of the hour playing on the floor with toys kept especially for them in a corner of the boudoir. As they grew older needlework and embroidery were substituted for the toys, the Empress disliking to see her daughters sitting with idle hands.

From six to eight the Emperor was busy with his ministers, and he usually came directly from his study to the eight o'clock family dinner. This was never a ceremonial meal, the guests, if any, being relatives or intimate friends. At nine the Empress, in the rich dinner gown and jewels she always wore, even on the most informal evenings, went to the bedroom of the Tsarevich to hear him say his prayers and to tuck him into bed for the night. The Emperor worked until eleven, and until that hour the Empress, the two older Grand Duchesses, and I read, had a little music, or otherwise passed the time. Perhaps it is worth recording that bridge, or in fact any other card games, we never played. Nobody in the family cared at all for cards, and only a little, once in a while, for dominoes. At eleven the evening tea was served, and after that we separated, the Emperor to write his diary for the day, the Empress and the children to bed and I for home. All his life the Emperor kept a daily record of events, but like all the private papers of the Imperial Family, the diaries were seized by the Revolutionary leaders and probably (although I still hope to the contrary) destroyed. The diaries of Nicholas II, apart from any possible sentimental associations, should be possessed of great historical value.

Monotonous though it may have been, the private life of the Emperor and his family was one of cloudless happiness. Never, in all the twelve years of my association with them, did I hear an impatient word or surprise an angry look between the Emperor and the Empress. To him she was always "Sunny" or "Sweetheart," and he came into her quiet room, with its mauve hangings and its fragrant flowers, as into a haven of rest and peace. Politics and cares of state were left outside. Never were we allowed to speak of them. The Empress, on her part, kept her own troubles to herself. Never did she yield to the temptation to confide in him her perplexities, the foolish and spiteful intrigues of her ladies in waiting, nor even lesser troubles concerning the education and upbringing of the children. "He has the whole nation to think about," she often said to me. The only care she brought to the Emperor was the ever precarious health of Alexei, but this the whole family constantly felt, and it had to be spoken of very often. The Imperial Family was absolutely united in love and sympathy. I like to remember of the children, who adored their parents, that they never felt the slightest resentment of their mother's attachment for me. Sometimes I think the little Grand Duchess Marie, who especially worshipped her father, felt a little jealous when he invited me, as he often did, to accompany him on walks in the palace gardens. This may be imagination, and at all events the child's slight jealousy never interfered with our friendship.

I think the Emperor liked to walk with me because he had need to talk to someone he trusted of purely personal cares which troubled his mind and which he could share with few. Some of these cares were of old origin, but had never been forgotten. I remember once he began to tell me, almost without any preface, of the dreadful disaster which attended his coronation, a panic, induced by bad management of the police, in the course of which scores of people were crushed to death. At the very hour of this fatal accident the coronation banquet took place, and the Emperor and Empress, despite their grief and horror, were obliged to take part in it exactly as though nothing had happened. The Emperor told me with what difficulty they had concealed their emotions, often having to hold their serviettes to their faces to hide their streaming tears.

One of the happiest memories of my life at Tsarskoe Selo were the evenings when the Emperor, all cares past and present forgot, sat with us in the Empress's boudoir reading aloud from the work of Tolstoy, Turgeniev, or his favorite Gogol. The Emperor read extremely well, with a pleasant voice and a remarkably clear enunciation. In the years of the Great War, so full of anguish and apprehension, the Emperor found relief in reading aloud amusing stories of Averchenko and Teffy, Russian humorists who perhaps have not yet been translated into foreign tongues.

Before the war the Emperor was pictured far and wide as a cruel tyrant deliberately opposed to the interests of his people, while the Empress appeared as a cold, proud woman, a malade imaginaire, wholly indifferent to the public good. Both of these pictures are cruelly misrepresentative. Nicholas II and his wife were human beings, with human faults and failings like the rest of us. Both had quick tempers, not invariably under perfect control. With the Empress temper was a matter of rapid explosion and equally, sudden recovery. She was often for the moment furiously angry with her maids whom too often she discovered in insincerities and deceit. The Emperor's anger was slower to arouse and much slower to pass. Ordinarily he was the kindest and simplest of men, not in the least proud or over-conscious of his exalted position. His self-control was so great that to those who knew him little he often appeared absent-minded and indifferent. The fact is he was so reserved that he seemed to fear any kind of self-revealment. His mind was singularly acute, and he should have used it more accurately to gauge the characters of persons surrounding him. It was entirely within his mental powers to sense the atmosphere of gossip and calumny that surrounded the Court during the last years, and certainly it was within his power to put a stop to idle and malicious talk. But it was rarely possible to arouse him to its importance. "What high-minded person would believe such nonsense?" was his usual comment. Alas! he little realized how few were the really high-minded people who, in the last years of the Empire, surrounded his person or that of the Empress.

Sometimes the Emperor found himself obliged to take cognizance of the malicious gossip which made the Empress desperately unhappy and in the end poisoned the minds of thousands of really well-meaning and loyal Russians. Beginning as far back as 1909 the tide of treachery had begun to rise, and one of the earliest of those responsible for the final disaster, I regret to say, was a woman of the highest aristocracy, one long trusted and affectionately regarded by the Imperial Family. Mlle. Sophie Tutcheva, a protegee of the Grand Duchess Serge, and a lady who was a general overgoverness to the children, was perhaps the first of all the intriguing courtiers of whom I have positive knowledge. Mlle. Tutcheva belonged to one of the oldest and most powerful families in Moscow, and she was strongly under the influence of certain bigoted priests, especially that of her cousin, Bishop Vladimir Putiata, who for ten years had lived in Rome as official representative of the Russian Church. It was he, I firmly believe, who inspired in Mlle. Tutcheva her antipathy to the Empress and her evil reports concerning the life of the Imperial Family. Mlle. Tutcheva, either of her own accord or encouraged by her relative, was continually opposed to what she called the English upbringing of the Imperial children. She wished to change the whole system, make it entirely Slav and free from any imported ideas.

Mlle. Tutcheva was, I believe, the first person to create what afterwards became the international Rasputin scandal. At the time of her residence in the palace at Tsarskoe Selo Rasputin's influence had scarcely been felt at all by the Emperor or Empress, although he was an intimate friend of other members of the Romanov family. But Mlle. Tutcheva spread abroad a series of the most amazing falsehoods in which Rasputin figured as a constant visitor and virtually the spiritual guardian of the Imperial Family. I do not wish to repeat these stories, but merely to give an idea of their preposterous nature I will say that she represented Rasputin as having the freedom of the nurseries and even the bedchambers of the young Grand Duchesses. According to tales purported to have their origin with her, Rasputin was in the habit of bathing the children and afterward talking with them, sitting on their beds.

I do not think the Emperor believed all these rumors, but he did believe that Mlle. Tutcheva was guilty of malicious gossip of his family, and he therefore summoned her to his study and rebuked her severely, asking her how she dared to spread idle and untrue stories about his children. Of course she denied having done anything of the sort, but she admitted that she had spoken ill of Rasputin. "But you do not know the man," protested the Emperor, "and in any case, if you had criticisms to make of anyone known to this household you should have made them to us and not to the public." Mlle. Tutcheva admitted that she did not know Rasputin, and when the Emperor suggested that before she spoke evil of him it might be well for her to meet him she haughtily replied: "Never will I meet him."

For a short time after this Mlle. Tutcheva remained at Court, but being a rather stupid and very obstinate woman, she continued her campaign of intrigue. She managed to influence Princess Oblenskaya, long a favorite lady in waiting, until she entirely estranged her from the Empress. She even began to speak to the children against their own mother, until the Empress, who felt herself powerless against the woman, actually refused to visit the nurseries, and when she wanted her children near her sent for them to come to her private apartments. Too well she knew the Emperor's extreme reluctance to dismiss any person connected with the Court, and she waited in silent pain until the scandal grew to such proportions that the Emperor could no longer ignore it. Then Mlle. Tutcheva was summarily dismissed and sent back to her home in Moscow.

So powerful was the influence of the Tutcheva family that this incident was magnified beyond all proper proportions, and the former over-governess of the Imperial children was represented as a poor victim of Rasputin, a man whom she had never seen and who probably never knew of her existence. The last I ever heard of Mlle. Tutcheva, who, by the way, was a niece of the esteemed poet Tutcheva, she was living in Moscow, under the special protection of the Bolshevik Government. Her cousin, the former Bishop Vladimir Putiata, I understand has for several years been a great favorite of those Communists who have prosecuted such brave and fearless opponents of church despoilment as the unhappy Patriarch Tikhon and others.

Of the Emperor I think it ought to be said that his education, under his governor, General Bogdanovich, was calculated to weaken the will of any boy and to encourage in Nicholas 11 his natural reserve and what might be called indolence of mind. But this I know of him that after his marriage he became much more resolute of temper and much more gentle of manner than other members of his family. It is certain that he loved Russia and the Russian people with his whole soul, and yet, under the political system for centuries in force, he had often to leave to people whom he knew only superficially many important details of government. Unquestionably it was a fault of the Emperor that he was over-confident, and only too ready to believe what was told him by people whom he personally liked. He was impulsive in most of his acts and sometimes made important nominations on the impression of a moment. It goes without saying that many of his officials took advantage of this overconfidence and sometimes acted in his name without his knowledge or authority.

Only too well for her own happiness and peace of mind did the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna understand her husband. She knew his kind heart, his love for his country and his people, but she knew also how easily influenced he could be by men in whom he reposed confidence. She knew that too often his acts were governed by the last person he happened to consult. But for all this I wish to say that the Emperor never appeared to his friends as a weak man. He had qualities of leadership with very limited opportunities to exercise those qualities. In his own domain he was "every inch an Emperor." The whole Court, from the Grand Dukes down to the last petty official and intriguing maid of honor, recognized this and stood in real awe of their Sovereign. I have a keen recollection of an episode at dinner in which a certain young Grand Duke ventured to utter an ill-founded grievance against a distinguished general who had dared to rebuke his Highness in public. The Emperor instantly recognized this as a mere display of temper and egoism, and his contempt and indignation knew no bounds. He literally turned white with anger, and the unfortunate young Grand Duke trembled before him like an offending servant. Afterwards the still indignant Emperor said to me: "He may thank God that the Empress and you were present. Otherwise I could not have held myself in hand." Towards the end of the Russian tragedy in 1917 the Emperor had learned to hold himself almost too well in hand, to subdue and to conceal the commanding personality of which he was naturally possessed. It would have been far better if he had used his personality and his great charm of manner to offset the tide of intrigue and revolution which in the midst of a world war overcame the Empire.

As long as I knew him, whether in the privacy of the palace at Tsarskoe Selo, in the informal life of the Crimea, on the Imperial yacht, in public or in private, I was always conscious of the strong personality of the Emperor. Everybody felt it. I can instance one occasion at a great reception of the Tauride Zemstvo when two men present were deliberately resolved to behave in a disrespectful manner to the Emperor. But the moment he entered the room these men found themselves completely overpowered. Their manner changed and they showed in every subsequent word and action their shame and regret. At one time a group of Social Revolutionaries were able to put on a cruiser which the Emperor was to visit a sailor charged with his Sovereign's assassination. But when the opportunity came the man literally could not do the deed. For his "weakness" this poor wretch was afterwards murdered by members of his party.

The character of the Empress was quite different from that of her husband. She was less lovable to the many, and yet of a stronger fiber. Where he was impulsive she was usually cautious and thoughtful. Where he was over-optimistic she was inclined to be a bit suspicious, especially of the weak and self-indulgent aristocracy. It was generally believed that the Empress was difficult to approach, but this was never true of sincere and disinterested souls. Suffering always made a strong appeal to the Empress, and whenever she knew of anyone sad or in trouble her heart was instantly touched. Few people, even in Russia, ever knew how much the Empress did for the poor, the sick, and the helpless. She was a born nurse, and from her earliest accession took an interest in 'hospitals and in nursing quite foreign to native Russian ideas. She not only visited the sick herself, in hospitals, in homes, but she enormously increased the efficiency of the hospital system in Russia. Out of her own private funds the Empress founded and supported two excellent schools for training nurses, especially in the care of children. These schools were founded on the best English models, and were under the general supervision of the famous Dr. Rauchfuss and of head nurse Miss Puchkina, a near relative of the great poet Puchkina. I could enlarge at length on the many constructive philanthropies of the Empress, paid for by herself, hospitals, homes, and orphanages, planned in almost every detail by herself, and constantly visited and inspected. After the Japanese War she built a Hotel des Invalides, in which hundreds of disabled men were taught trades. She also built a number of cottages with gardens for wounded soldiers and their families, most of these war philanthropies being under the supervision of a trusted friend, Colonel, the Count Shulenburg, of the Empress's favorite Lancers.

The Empress possessed a heart and a mind utterly incapable of dishonesty or deceit, consequently she could never tolerate either in other people. This naturally got her heartily disliked by people of society to whom deceit was a matter of long practice. Another quality condemned in the Empress because entirely misunderstood, was her care as to expenses. Brought up in the comparative poverty of a small German Court, the Empress never lost the habit of a cautious use of money. Quite as in private families, where economy is an absolute necessity, the clothing of the young Grand Duchesses when outgrown by the elders were handed down to the younger girls. In the matter of selecting gifts for guests, for relatives, or at holidays for the suite, the Emperor simply selected from the rich assortment sent to the palace objects which best pleased him. The Empress, on the other hand, always examined the price cards and considered before choosing whether the jewel or the fur or the bijou, whatever it was, was worth what was asked for it. The difference between the Emperor and the Empress in regard to money was a difference in experience. The Emperor, all his life, had everything he wanted without ever paying a single ruble for anything. He never had any money, never needed any money. I can recall but one solitary instance in which the Tsar of all the Russias ever even felt the need of touching a kopeck of his illimitable riches. It was in 1911 when their M aj esties began to attend services at the Feodorovsky Cathedral at Tsarskoe Selo. In this church it was the custom to pass through the congregations alms basins into which everyone, of course, dropped a contribution, large or small. The Emperor alone was entirely penniless, and embarrassed by his unique situation he made a representation to the proper authorities, after which at exact monthly intervals he was furnished with four gold pieces for the alms basin of the Feodorovsky Cathedral. If he happened to attend an extra service he had to borrow his contribution from the Empress.

But if the Emperor carried no money in his pockets it was well enough known that he commanded vast sums, and it was characteristic of the sycophants who surrounded him that he was constantly importuned for "loans," for money to help out gambling or otherwise impecunious officers who, aware of the Emperor's great love for the army, played on it to their advantage. One day when the Emperor was taking his usual brisk walk through the grounds before tea a young officer who had managed to conceal himself in the shrubbery sprang out, threw himself on his knees, and threatened to kill himself on the spot unless the Emperor granted him a sum of money to clear the desperate wretch of some reckless deed. The Emperor was frightfully enraged - but he sent the man the money demanded.

The Empress had always handled money and knew quite well how to spend it wisely. From the depths of her honest soul she despised the use of money to buy loyalty and devotion. For a long time after my first formal service as maid of honor, with the usual salary, I received from her Majesty literally nothing at all. From my parents I had the income from my dowry, four hundred rubles a month, a sum entirely inadequate to pay the running expenses of my small establishment with its three absolutely indispensable servants, and at the same time to dress myself properly as a member of the Court circle. The Empress's brother, Grand Duke Ernest of Hesse, was one of the first of her intimates to point out to her the difficulties of my position, and to suggest to her that I be given a position at Court. The suggestion was not welcomed by Alexandra Feodorovna. "Is it not possible for the Empress of Russia to have one friend?" she cried bitterly, and she reminded her brother that her relation and mine were not without precedent in Russia. The Empress Dowager had a friend, Princess Oblenskaya; also the Empress Marie Alexandrovna, wife of Alexander III, had in Mme. Malzoff an intimate associate, and neither of these women had any Court functions. Why should she not cherish a friendship free from all material considerations? However, after her brother and also Count Fredericks, Minister of the Court, had pointed out to her that it was scarcely proper that the Empress's best friend and confidante should wear made-over gowns and go home from the palace on foot at midnight because she had no money for cabs, the Empress began to relent a little. At first her change of attitude took the form of useful gifts bestowed at Christmas and Easter, dress patterns, furs, gloves, and the like. Finally one day she asked me to discuss with her the whole subject of my expenses. Making me sit down with pencil and paper, she commanded me to set forth a complete budget of my monthly expenditures, exactly what I paid for food, service, light, fire, and clothing. The domestic budget, apart from my small income, came to two hundred and seventy rubles a month, and at the orders of the Empress I was thereafter furnished monthly with the exact sum of two hundred and seventy rubles. It never occurred to her to name the amount in round numbers of three hundred rubles. Nor did it occur to me except as a matter of faint amusement. Of course I was often embarrassed for money even after I became possessed of this regular income, and even later when it was augmented by two thousand rubles a year for rent, and it often wrung my heart to have to say no to appeals for money. I knew that I appeared selfish and hard-hearted. The truth was that I was simply impecunious.

Tsar Nicholas II