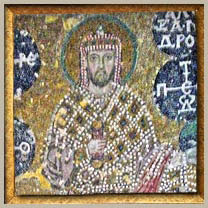

Here's a page I wrote that is dedicated to the very hard to find mosaic in the upper gallery of Hagia Sophia of the Byzantine Emperor Alexander - Alexandros

Chapter XVI

He is Released

In the morrow we were horrified to hear that the Bolshevists had made many victims at Tsarskoe. Since their arrival they had shot a number of persons, including two priests, Father John and Father Phoka, for having set the church bells pealing and having organised a procession of the Cross (Krestny-hod). Towards noon, the car which the day before had taken the Grand Duke, returned to Tsarskoe and with Gueorguenberguer. He brought a permit for me and Vladimir, and it was decided that at two o'clock, after lunch, he should return here and that we should go with him to Smolny. This. was done. We spoke little en route. He confessed to us that he had not slept for three nights; thus it was that he slept profoundly as soon as he got into the car. We were alone, Vladimir and I, and during this drive of fifteen miles we spoke in low tones of what was weighing on our hearts. When we reached town, the joltings awoke the sleeper and he began to talk to us, telling us how he had been a schoolmaster in a village near Novgorod. From his youth onwards he had had very liberal ideas. On the arrival of Lenin he had become one of his most fervent disciples. He seemed to be sincere, and for some time I imagined that we had in him a protector and that, Communist though he was, he was just and upright. We were to be disillusionised, but not until later.

On arriving at the Convent of Smolny, I observed with regret that this fine building, erected by' Catherine I and transformed into a convent for young girls of noble birth by the Empress Marie, wife of Paul I, had become in the course of a few days an untidy, dirty barracks, full of noisy soldiers. We went up to the second floor and after many turnings in the enormous corridors we came to a stop in front of a door. Gueorguenberguer entered alone and after a moment came back for us. With what emotion I embraced my beloved, with what joy I found him safe and sound, although tired and pale. In the dreadful room, stripped of its furniture, in which he had to live, there was only a campbedstead (without a cover) on which he had thrown his fur-coat, a small table, another tiny table with a white water-jug and a basin, and two chairs. One asked oneself with amazement: "What was the reason of this?" Alas, the Calvary had only begun!

I had brought with me some sandwiches, some chicken, some cakes and some milk, and my dear husband ate with appetite. Since he had left Tsarskoe the day before, after lunch, he had only had a little tea and a plate of soup which, out of pity, he had allowed his warders, the three sailors, to share with him. It was astonishing how eventhe most revolutionary soldiers came under the spell of the charm and prestige of the Grand Duke. His meal over, he told me that on the day before they had shut him up with Alexanderin a room for two hours. Then an armed man (a Red Guard), followed by ten others, came in and read out aloud:

"By order of the Revolutionary Soviet Paul Alexandrovitch Romanoff is condemned to imprisonment in the fortress of Peter and Paul.

"The Grand Duke felt dizzy for a moment, but he heard distinctly our good Alexander intervene with the words:

"Comrades, there is a misunderstanding here. Comrade Gueorguenberguer has assured us that no harm would be done to Paul Alexandrovitch. He is innocent, and, what is more, he detests Kerenksy - as we all detest him."

"Yes," replied the man who had read the warrant of arrest, "that is all right; but Rodzianko is at this moment shooting down our men in Moscow. We need hostages.""But Paul Alexandrovitch detests Rodzianko as much as Kerensky and Savinkoff," Alexander rejoined.

Thereupon entered Bontch-Bronevitch, a type of be-spectacled professor. He was the charge de affaires of the Soviet of the People's Commissaries. My son had known him formerly in other circumstances, but both pretended not to recognise each other.

"Paul Alexandrovitch," said Bontch-Bronevitch, " I am able to assure you that you have been arrested through a misunderstanding. You will not go to the fortress of Peter and Paul, but I cannot set you free to-day. I am almost sure that you will be set free to-morrow. Only you will have to remain some days in Petrograd."

After the Grand Duke had told me all this we decided as soon as he was free we should go and occupy the flat of my daughter Olga, who had left for Sweden. This flat was in one of the houses which belonged to the Grand Duke. I left, my husband somewhat calmed, and went to my daughter's flat at No. 29, Admiralty Canal, in order to arrange everything for our move in. My poor dear mother was delighted over the plan. She occupied the flat below, and the idea that she would see us often for some time filled her with joy.

Next day, early, I took the children, Miss White, Jacqueline and my maid, and we installed ourselves in the flat of my daughter Olga Kreutz. At three o'clock in the afternoon I went to Smolny with my permit in the hope of carrying back my husband with me. I remained with him until six. He told me that the three sailors had come, to see him on the evening before and to ask him to read some paper to them. It was a horrible, Communist sheet which did not interest them at all. One of them went to get a so-called bourgeois paper for at that moment the Press was not yet stifled in Russia as it was in 1918, and as it has been since.

At six the President of the Commission, Comrade Alexeievsky, came in, He was a sailor, wearing the wide-open collar, and had a lot of curly hair. A fine type of the Northern Russian. He was from Mourmansk. Comrade Alexeievsky came to tell me not to wait as there were some formalities to be got through-he would himself bring Paul Alexandrovitch along to his new domicile. And, in due course, at eight o'clock my dear husband arrived escorted by Alexeievsky and by his doctor, Obnissky, in a superb automobile of the Court, with electric pharos Jights, etc. It was this automobile that was at the bottom of the legend that the Grand Duke had seen Lenin and that it was Lenin in person who took him home.

We spent eleven calm. and almost happy days after this excitement. During this time veritable battles took place in Moscow, where the remnant of the Provisional Government was struggling in desperation against the Bolsheviks. In the course of the fighting the Kremlin and the ancient belltower of Ivan-Veliky were greatly damaged by the guns, The Bolsheviks at last remained masters of the ground. On November 13th/26th, on our request to be allowed to return to Tsarskoe, Comrade Alexeievsky arrived with an order signed by Smolny permitting us to do so. We all started out in our big car, which has seats for eleven. On arriving home, we made Alexeievsky remain to lunch, and during the meal I persuaded him of the versatility [sic] of the Bolshe regime, and I converted him to the Monarchy. He was a shrewd and intelligent youth who would not give expression to his innermost feelings. I think he was, above all, an opportunist, and that he was ready to serve all those who were in power.

After lunch the Grand Duke ventured on a somewhat risky move. He said to Alexeievsky:

"I should have liked to give you a souvenir, to make you a present, in order to thank you for the kind offices you have rendered me. It wasn't possible for me to go into the shops in Petrograd. Accept this portfolio with what it contains."

There were 4,000 roubles inside it. Alexeievsky was so enraptured that he kissed the Grand Duke's shoulder, as old retainers used to do in former days, and went off thanking us profusely and with many gesticulations. I myself gave him several bottles of vodka, a liquor forbidden during the war, and this brought his joy to a climax. I must do him the justice to say, that whenever he could he was of service to us, but he always had in return some bottles of vodka, a drink for which he had a special relish. Then one day he disappeared. It was said that he fled to Mourmansk. We never heard of him again.