In exile at Rakitnoe - The first phase of the Revolution - The Emperor's abdication - He bids farewell to his mother - My return to St. Petersburg - A singular proposal.

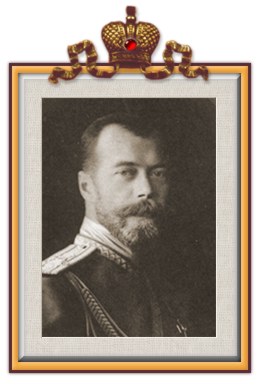

LEFT: Nicholas II.

LEFT: Nicholas II.

The journey was long and unpleasant, but I had the delightful surprise of finding Irina and my parents at Rakitnoe. They had been warned of my arrival by my father-in-law, and had immediately left the Crimea to join me, leaving our daughter and her nurse at Ai-Todor.

I knew that my letters would be opened by the police, so I had been unable to write more than a few brief words to my wife. My family, therefore, knew nothing of the events in St. Petersburg, beyond what people were saying, and had naturally been seriously alarmed. Two telegrams received almost simultaneously put the finishing touch to their anxiety. Qne from the Grand Duchess Elisabeth in Moscow ran thus: "My prayers and thoughts are with you all. God bless your dear son for his patriotic act." The other, from St. Petersburg, was from the Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich: "Body found-Felix quite calm." My part in Rasputin's assassination had all at once become official...

Irina told me that she had wakened during the night of December 29 and, on opening her eyes, had suddenly seen Rasputin. He was dressed in an embroidered silk blouse and seemed immensely tall. The vision lasted only a second. My arrival at Rakitnoe did not pass unnoticed but the inquisitive found that strict orders had been given that no one was to be admitted. I had a visit from the magistrate entrusted with the inquiry into Rasputin's death. Our meeting was a complete farce. I expected to see a cold and dignified official, severe and uncompromising, with whom I would have to wage a battle of wits. But instead, I found a man so deeply moved and so emotional that I thought he was going to fling himself into my arms. During lunch, he rose to make a patriotic speech and to drink my health. The conversation turned on life in the country, and my father asked him if he was fond of shooting. "No," replied the worthy official, who had a one-track mind, "I've never shot anybody." He looked very uncomfortable when he realized what he had said.

After lunch, he and I had a long talk. For some time he talked at random not knowing how to broach the subject. I came to his rescue by telling him that I had nothing to add to my previous statements. He at once seemed much relieved, and during the rest of our conversation Rasputin's name was not even mentioned.

Life at Rakitnoe was monotonous. We often went for long sleigh drives.. It was a beautiful winter, cold and dry. The sun shone brightly and there was not a breath of wind, so we could drive in open sleighs with the temperature well below zero, without feeling the cold. In the evening, we read aloud.

The news from St. Petersburg was most alarming. It was obvious that the people had all lost their heads and that the debacle was imminent.

The Revolution broke out on March 12. Buildings all overthe capital were set on fire, and there wa sheavy shooting in the streets. A great part of the Army and of the police joined the Revolution - among them the Cossacks of the Household, the elite of the Imperial Guard. After long discussions with the Soviet of Workmen's and Soldiers' Representatives, a Provisional Government was formed under the presidency of Prince Lvov, with Kerensky as Minister of justice at the demand of the Socialist Party.

The Emperor abdicated on March 15. So as not to be separated from his delicate son, he handed over the crown to his brother, the Grand Duke Michael. The text of this historic document is well known, and I recall its noble words with the deepest emotion:

We, Nicholas II, by the grace of God Emperor of all the Russias, Tsar of Poland, Grand Duke of Finland, etc., etc., hereby make known to all Our loyal subjects: At this time of bitter strife against a foe who for nearly three years has been striving to invade Our country, it has pleased God to send down on Russia a fresh and grievous trial. The disturbances which have begun in our midst threaten to have a disastrous effect on the conduct of this fearful and relentless struggle. The destiny of Russia, the honor of Our heroic army, the welfare of the people, the whole future of Our beloved country, make it imperative that the war be brought at all costs to a victorious end. The enemy is making his last efforts, and the hour is at hand when Our valiant army, with the help of Our gallant Allies, will defeat him conclusively. In these decisive days so critical for the very existence of Russia, We deem it Our duty to do Our utmost to facilitate the close union of Our people so that in a common effort of the whole nation a rapid and decisive victory may be won. That is why, in agreement with the Duma of the Empire, We have thought fit to abdicate the throne of Russia and relinquish Our sovereign power. Not wishing to be parted from Our beloved son, we bequeath Our heritage to Our brother, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, and we give him Our blessing on His accession to the throne. We urge Him to govern Russia in close communion with the Representatives of the legislative Assemblies, and to swear inviolable allegiance to them in Our beloved country's name. We appeal to all the loyal sons of Russia, and ask them to fulfill their sacred and patriotic duty by obeying the Tsar and, in this time of grave national crisis, helping Him, together with the Representa tives of the Nation, to lead the Russian State into the path of glory, prosperity and victory. God save Russia.

Nicholas

On the following day, March 16, the Grand Duke Michael signed his provisional abdication. Kerensky, who had practically extorted this from him, was most eloquent in his thanks.

The government having given the Emperor "permission" to bid farewell to the Army, the Dowager Empress and my father-in-law immediately left for Kiev, and from there went to General Headquarters in Mohilev.

At the station, Nicholas II remained alone with his mother in her private train for two hours. Their conversation was not divulged. When my father-in-law was invited to join them, the Empress was weeping bitterly. The Tsar stood motionless and silent, smoking.

The Provisional Government yielded to the demands of the Soviet and ordered the Tsar's immediate arrest. The infamous order of the day Number One was published; it empowered the soldiers to choose their own officers and to form regimental soviets, and it abolished saluting. This meant the end of all military discipline. In certain garrisons the men were already massacring their officers. It was the end of the Russian Imperial army.

Three days later, the Emperor left for Tsarskoe Selo where he was to be interned with his family. He wore a plain khaki tunic and the cross of St.. George. His train was standing side by side with that of the Dowager Empress, who stood weeping at the window. She made the sign of the cross and a gesture of benediction. As the train moved out, the Tsar waved good-by. This was the last time he was to see his mother.

On reaching Tsarskoe Selo, the Emperor was forsaken by all. The only one to accompany him to the Alexander Palace was Prince W. Dolgorukov.

I was allowed to leave Rakitnoe at the end of March and we all returned to St. Petersburg. Before we left, a service was held at Rakitnoe; the church was full of weeping peasants. "And how are we going to live?" they asked. "Our Tsar has been taken from us!"

At Kharkov station we wanted to go to the buffet. We had to force our way through a crowd of jostling men and women hailing each other as "comrade" Someone recognized me and spoke my name. The crowd closed in on us, and in their enthusiasm started to shove and push, till we were almost suffocated. I had the unpleasant feeling that the very people who were cheering us today might just as easily lynch us tomorrow. Some soldiers came to our help, and cleared a way for us to the refreshment room. The crowd tried to rush in after us, and the doors had to be closed. They called on me to make a speech but I refused, saying that I was unable to speak in public. just then, we were told that the train in which the Grand Duke Nicholas Nicholaievich was returning from the Caucasus had arrived in the station. To reach him, we had to make our way once more through the howling mob, which was now cheering the Grand Duke. He embraced me warmly, exclaiming: "At last we'll be able to triumph over Russia's enemies!" Our meeting was brief, as his train was leaving almost immediately. On getting back to ours, I met a singer called Altchevsky in the corridor. He told me that he had been in the country getting treatment for a serious nervous complaint; he came into our compartment and offered to sing for us. Suddenly in the middle of a song he stopped, and staring at me wildly asked: "Why are you looking at me like that? I can't sing any more," Taken aback, I begged him to continue, but be refused and launched into a long diatribe in a voice which grew louder and louder. His shouting attracted the attention of a friend of his in the next compartment who managed to find a doctor on the train to give him an injection. But in the dead of night, his howls echoed through the train, louder than ever. In the general atmosphere of strain and tension, this ghastly encounter with a madman was the highlight of our nightmare journey.  Left: A View of Arkangelskoye.

Left: A View of Arkangelskoye.

We found St. Petersburg very much changed. The confusion in the streets was indescribable. Most people were wearing red cockades. Our own chauffeur had thought it would be prudent to wear a red bow when meeting us at the station. "Take it off!" my mother cried indignantly.

One of the first things I did was to see the Grand Duchess Elisabeth in Moscow; I had not seen her since the tragic events in March. She came up to me with her eyes full of tears, and blessed and kissed me. "Poor Russia," she said, "what a terrible ordeal lies ahead of her! But we must bow before the will of Heaven. We are helpless. We can only pray and beseech God's mercy."

She listened with close attention to my account of the tragic night of December 29. "You could not act otherwise," she said when I had finished. "You made a supreme attempt to save your country and the dynasty. It is not your fault if the result is not what you hoped for. The fault lies with those who failed to do their duty. It was no crime to kill Rasputin; you destroyed a fiend who was the incarnation of evil. Nor is there any merit in what you did: you were destined to do it, just as anyone else might have been."

She told me that a few days after Rasputin's death the mothers superior of several convents had come to see her, to tell her of the disturbing events that had taken place in the communities on December 29. During the night offices, priests had suddenly gone mad, blaspheming and shrieking; nuns ran about the corridors howling like souls possessed and lifting their skirts with obscene gestures.

"The Russian people cannot be held responsible for events to come," continued the Grand Duchess. "Poor Nicky, poor Alix, what suffering awaits them! God's will be done. But even though all the powers of hell may be let loose, Holy Russia and the Orthodox Church will remain unconquered. Some day, in this ghastly struggle, Virtue will triumph over Evil. Those who keep hose who keep their Faith will see the Powers of Light vanquish the Powers of Darkness. God punishes and pardons."

ABOVE: The Moika Palace.

From the day of our arrival in St. Petersburg, our house on the Moika was filled with a continuous stream of people; we found this very exhausting... Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma and a distant relative, was among our most frequent visitors. One day my mother sent for me. Irina and I went up to see her and found her deep in conversation with Rodzianko. The latter rose as I came in, walkedup to me and said point-blank: "Moscow wishes to proclaim you Emperor. What do you say to that?"

This did not come as a surprise, as I had been approached several times since our return by people of different classes: officers, politicians, priests. Later on, Admiral Koltchak and the Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich also discussed the matter with me. The Grand Duke said: "The throne of Russia is neither hereditary nor elective: it is usurpatory. Take advantage of the Circumstances; you hold all the trumps. Russia cannot go on without a monarch, and the Romanovs are discredited; the people don't want them back."

I was deeply dismayed by the irony of the situation. The very man who bad killed Rasputin in order to save the dynasty was himself requested to play the part of usurper!

Meanwhile, I was becoming very anxious about Dmitri, who had fallen ill at Teheran and was in despair at being so far from home.

For questions or comments about this online book contact Bob Atchison.