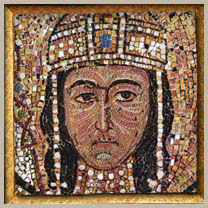

EMPEROR AND EMPRESS

It is difficult to offer an estimate of character of the one without the other. More difficult, perhaps, to speculate upon what would have happened if they had never met, and he had found another consort.

The Emperor - till too late - was a confirmed autocrat, apart, I believe, from the influence of the Empress, who had identical views as to the government of the country.

In a speech made in January 1895 he had said: 'Let them [the people] know that I, devoting all my efforts to the prosperity of the nation, will preserve the principles of autocracy as firmly and unswervingly as my late father of imperishable memory.'

It was the teaching of his boyhood, and he felt it his duty to hand these principles on.

It is possible, however, that had he married someone else, possessed of a clear head and the influence which might have been exercised with him by one who, though not a courtier, was so near him as to be available at any time to suggest and advise, circumstances might have worked out quite differently. As it was, even a courtier who had the good sense to speak out with honest endeavour - and how rare such courtiers areto be of service went to the wall. Whether that was the independent action of the Emperor alone, or of some additional pressure from the Empress, I do not know. The fact remains that an already confirmed autocrat became more so under her influence.

That they honestly believed that it was the right system for the government of their country is certain. Thus there existed a couple working hand in hand, as they believed and imagined, for the good of their country, and the dangers of the autocratic system became intensified by the fact that the stronger influence of the two was that of the Empress, whose ill health and neurotic character not only cut her off from the outside world of Russia, but brought her under other influences, which reacted again upon the Emperor and finally brought him, loyal and devoted as he was, to his fall.

Appointments and dismissals of ministers lay entirely in the hands of the Emperor, but the adviser who brought them about was in most cases the Empress.

The combination of an Emperor so devoted to his Empress that her word was law, and of an Empress led unconsciously by the worst possible advisers, brought about their ruin and that - for the time being - of their country.

According to M. Gilliard's account of the last days of the Imperial family, those fine qualities of the Empress which showed themselves in her care and devotion to the sick and wounded during the war became still more evident in the days of distress, misery and ignominy which crowned the end.

Even her critics and her enemies, and she had many, will accord her a meed of praise for the courage and devotion which, even in what must have been the most intense purgatory to her, she showed unselfishly for her husband and children.

And so in death they were not divided.

I was much struck, closely interested as I was in Russian affairs, at the apparent lack of interest, almost amounting to indifference, with which the news of the fate of the Russian Imperial family was received in England. It was probably to be accounted for by two reasons, the number and rapidity of the march of events connected with a great war and its sequences, and the uncertainty as to the truth of the reports, confirmation or contradiction being almost daily reported, till a lack of interest ensued.

The fact remains, however, that one of the greatest tragedies in history was, to all appearances, quickly forgotten, except by those to whom it came very near.

As to the alleged pro-Germanism of the Emperor and Empress, I think I have said enough in the preceding pages to dispel the idea of this accusation.

I may add another note upon the subject.

As is known to those taking an interest in the question, a commission was appointed by the Revolutionary Government with the duty assigned to it of searching through all the letters, both official and private, of the Emperor and Empress.

The Commission apparently did its work with zeal and such enthusiasm as can be found by those who enjoy the prying into the personal and private and family affairs of other people.

No doubt, all agog for some scandalous discovery, or proof of guilt by the discovery of letters to the enemy, or expressions of affection for the Germans, they scanned the pages before them, word for word.

What was the result?

M. V. M. Roudnieff, one of its members, allowed indignation to master his surprise, and published his personal report, proving to the world at large that not a jot or a tittle of evidence was to be found.

The mysterious intrigues of the Empress with the enemy vanished.

The accusations of disloyalty on the part of the Emperor were exploded.

Those who knew them received this news with no surprise. Those who professed to know them, and maligned them, probably preferred to look elsewhere for any other kind or other sort of news they could find.

What followed? The irony of fate threw the country where accusations of disloyalty had dethroned an Emperor and Empress, into the arms of the very enemy with whom they had been supposed to intrigue, and Brest-Litovsk and Bolshevism ruined Russia.

Comments on this site should to: Bob Atchison