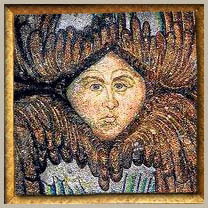

Here's s page of wonderful images of the great mosaic icon of Christ in the upper gallery of Hagia Sophia - otherwise known as Saint Sophia.

- A Scotman in Russia

- The First Steps

- Russian Military Flying Schools

- The Imperial All Russia Aero Club

- General Baron Kulbars & Aviation

- The Imperial Russian Technical Society

- The Prototype of the Zeppelin

- Contruction, Aviators & Workmen

- Famous Russian Flying Men

- I.I. Sikorsky

- Foriegn Aviators in Russia

- Heir Fokker's Russian Lady Pilot

- Just Before the War

- Aerial Russia & the British Press

- Aviation & the Russian Press

- By Way of Conclusion

Chapter XI - Foriegn Aviators in Russia

Great Britain paid very little attention to Russia before the war and only the very few Britons who lived in my country had the smallest realisation of the quality of the Russian nation. This was a general truth. No one here appears to have had the smallest idea of Russia's technical development or scientific achievement, and certainly no one had the slightest knowledge of the condition of Russian aviation. Despite the efforts of a handful of enthusiasts, aviation had been sadly neglected in England itself, and it was therefore not surprising that there should be little interest in the progress of the art in foreign countries. The French and the Germans did not share this indifference to Russian affairs. They paid frequent visits to Russia. They studied the psychology of the iRq~sian people and they endeavoured to introduce their sciences, their arts, and their industries into the vast empire of the Czar. These visitors experienced a great surprise when they discovered that the prevailing idea that. Russia was only a half-civilised country was an entire mistake. The enormous and speedy improvement of aviation in Russia astonished the foreign observers. They immediately, however, took advantage of the widespread interest, and numerous foreign aviators visited the various Russian aerodromes. The first stranger pilot who went to Russia was Legagneaux, who visited Petrograd in 1909, and made two or three flights from Gatchino, a suburb of the capital, on his Voisin biplane. This was one of the first machines constructed by the French firm. In those early days there were absolutely no facilities for flying in Russia even the aerodrome at Gatchino was not in existence and Legagneaux's experiences were very unfortunate. A great crowd had assembled to watch his flight but unluckily his engine suddenly stopped. He was obliged to land in the marshes and his machine was badly broken. The public disappointment was very great. High prices were charged for entrances into the field from which the flights took place and the Press severely criticised the French aviator for his failure. In the spring of 1910 another Frenchman, M. Albert Guigot, arrived in Petrograd with a small BIedot mono-plane. He had been specially invitcd by the committee of the Imperial All Russia Aero Club and the race-course at Kolomiagi near Petrograd was put at his disposal. Guigot was more fortunate than his predecessor, and was warmly received by both the public and the press. So warm was the cordiality and friendship of his Russian confreres that even two years afterwards, Guigot recalled his sojourn in Russia with real enthusiasm and in letters to his friend Kennedy described the pleasures of his visit with true French eloquence. In this same spring of 1910, and also by invitation of the Aero Club, Hubert Latham brought his Antoinette monoplane to Petrograd, but he was even more unlucky than Lagagneaux. His machine only succeeded in making a short then crashed down, breaking the fuselage and the wings. Latham had not brought any spare parts with him, and he immediately returned to France. Soon afterwards the Russian aviators received a visit from the Baroness de la Roche, who brought with her her Voisin biplane. Madame de la Roche made three short flights in Petrograd, but as a matter of fact during her visit she was more interested in the delights of the brilliant society of Petrograd than in the science of aviation. There was indeed a tremendous desire to meet a lady aviator for the first time. It should be added that these early foreign visitors were remunerated with characteristic Russian generosity. Latham, for instance, received a thousand pounds for his abortive flight.

By the spring of 1911, when a real aerodrome I had been prepared in Petrograd, an aviation week was initiated, thanks largely to the efforts of Paui Beckel and Boris Souvorin. This week was the occasion of visits from several international pilots: Christians on a Farman, Vincias on an Antoinette, Morane on a Bleriot, and Cheyalier on a Nieuport. Christians was a cool-tempered but not very interesting pilot and for the most pan he was content to circle round and round the aerodrome at a height of one hundred to one hundred and fifty feet. Vincias accomplished some short flights accompanied by several accidents and he was seen very little in the air. The Russians were certainly not impressed by the Antoinette, and the Government decided without hesitation not to purchase any machines of that type. Morane produced a great impression on the public by his splendid and courageous flights on his Bleriot, but the champion of the week was unquestionably Chevalier on his fifty horse power Kieuport. The speed of the machine and the evolutions performed by the aviator were astonishing and delightful. It is rather curious to remember that most of the scientific professors who carefully inspected the Nieuport , exhibited in the Petrograd International Exhibition, only two weeks before Chevalier's appearance in the new aerodrome, categorically declared that the machine could never fly. The pilot must have enjoyed himself immensely when these same professors warmly applauded the flights' skill.

Bleriot himself visited Petrograd during the first International Aviation Exhibition, but he never flew in Russia. Some time later M. Segall, the inventor of the Gnome engine, delivered a series of lectures on his inventions to the Imperial Russian Technical Society, and lectures were also delivered in Petrograd by M. Esnault-Peltri though he, like Bleriot, did not fly in Russia.

Many German aviators went to Russia, some of them by invitation, but most of them influenced by characteristic German curiosity and eager to know exactly what Russia was doing in the world of the air. The celebrated Wright pilot Abramovitch, who is, by the way, a Russian by origin, appeared in Petrograd in 1912 and rendered priceless service to the Russian Military authorities by the information he was able to give them concerning the state of military aviation in Germany. Abramovitch had all the patriotic feelings of a Russian and he professed to have little sympathy with Germany as a people. Had Abramovitch lived to see the Great War he might have rendered great service to his native land, but unfortunately soon after his return to Germany he fell during one of his flights and was killed. Abramovitch always flew on a German Wright biplane and was universalIy regarded as Germany's best pilot on such aeroplanes.

At the same time as Abramovitch, the famous Lieutenant Bier came to Petrograd bringing two aeroplanes with him, one of them a big Mars monoplane and the other an Albatross biplane. He only remained three days in the Russian capital. His flights were admirable and he accomplished with extraordinary accuracy everything he attempted to do. The military appearance of this typical Prussian lieutenant could not be hidden by his mufti, and it was soon suspected that Herr Bier was no simple civilian but an officer of the flying corps. He was asked if this was so.

"Oh yes, I am an officer," frankly confessed Lieutenant Bier.

"Then why did you come to Petrograd, since you as an officer could certainly not be invited by the committee to take part in the competitions?"

"I came," was the reply, "to discover for myself the state of your aviation and in order to avoid a difficult position I retired from the German army before I left Berlin."

Bier was indeed nothing but a German spy who did not bother himself to hide his position, but, wIth true German cynlclsm, confessed it to the Russian officers whom he met in Petrograd. The moment he returned to Germany he was restored to his position in the army.